In Africa’s richest city, the morning commute can still feel like Russian roulette. Since passenger rail collapsed during the pandemic after widespread vandalism, the city now moves mostly by mini-bus taxi, not by timetable, with costs climbing and risks following right behind.

According to a Bloomberg city report, a Soweto commuter pays about 1,400 rand ($79) each month for a 26-kilometer trip to the city along a route that’s plagued with violence, having claimed about 60 lives (both drivers and commuters) in the first quarter of 2025.

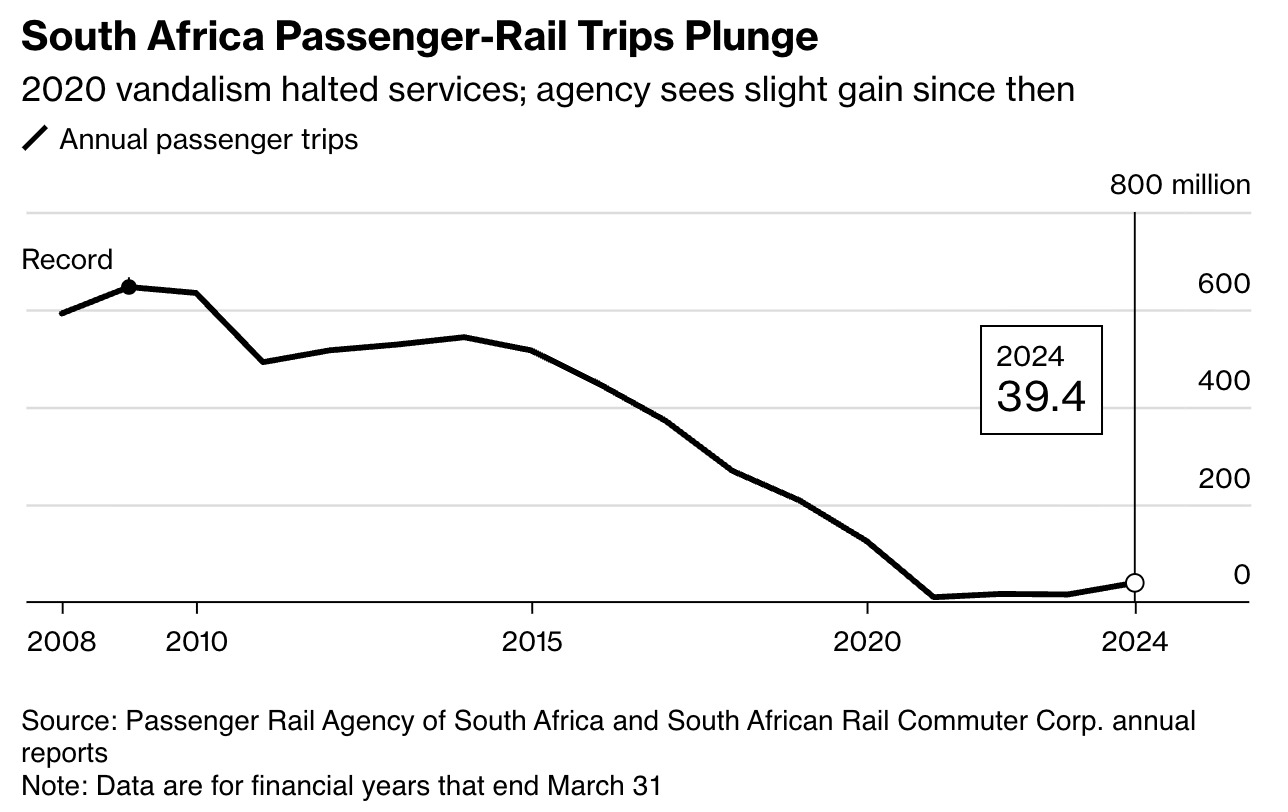

Although rail transit is inching back to 39 million annual trips based on FY2024 readings—up from 10 million in FY2021—it is far from the 646 million peak in 2009.

The Gautrain is discounting fares, and the city is trying to rescue its bus network, yet most riders still face long, complicated transfers. Peak hour should not feel like a gamble, but that is the story of mobility in one of Africa’s richest cities.

Make Mobility Work: Restore Rail, Rein In Taxis, Integrate Fares in Johannesburg

Minibus taxis are not a new development in the South African space; in fact, this form of mobility has dominated the region’s landscape, including part of its history and policy.

Apartheid planning placed Black communities far from jobs, and deregulation in 1989 enabled a private, cash-based taxi industry to fill the gap—enter the minibus taxi.

When PRASA’s network became 95% unusable in 2020, the shift accelerated. According to a 2025 Bloomberg report, taxis now account for about 26% of all trips nationwide, buses 4.5%, and trains 0.7%.

The taxi sector moves an estimated 15 million passengers each day, supplied by over 16000 buses, and generates roughly 90 billion rand ($5.07 billion USD) in revenue, a sizeable sum for a deregulated sector. This has led to many groups vying for the driving seat in the business.

Daily life is punishing for riders. Many leave before dawn, change vehicles multiple times, and pass through taxi ranks where route monopolies fuel turf wars.

The report also highlights that about 85% of public-transport users in Johannesburg rely on taxis. Complaints include red-light running, overcrowding, and poor maintenance.

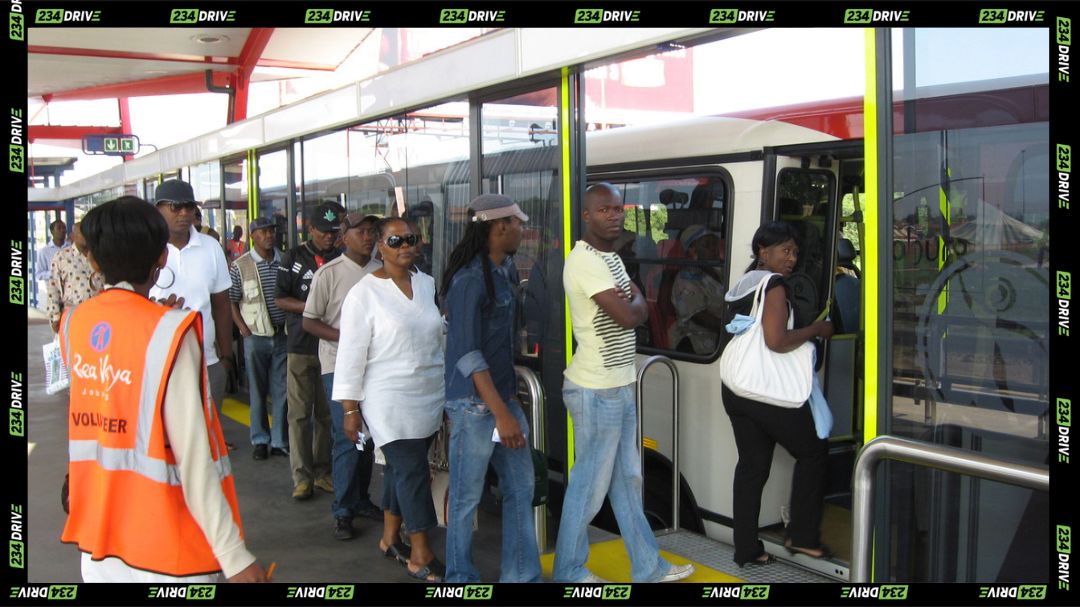

Attempts to build alternatives have struggled. Rea Vaya, the bus rapid transit system with dedicated lanes, entered business rescue in 2023 after route delays, bus shortages, and debt tied to PioTrans, the initial operator formed by taxi owners.

The Gautrain, a separate high-speed rail, works well for a higher-income market: a CBD to Sandton taxi is about 22 rand ($1.21), while the Gautrain peak fare is about 42 rand ($2.31).

The PPP endeavour has had an expansion planned since 2021 but has stalled due to a mix of funding and contract agreements between the South African government and Gauteng Province (who retain ownership of the asset).

Although a 50% discount exists for lower-income riders on the available platforms, an attempt by the government to ease the burden of its citizens.

To restart the next BRT corridor, the city is repurposing 68 unused Gautrain buses and backing the new Alexandra Bus Co. Provincial leaders have pushed ceasefires and dispute-resolution mechanisms among taxi associations after deadly flare-ups.

Right now, the network runs on improvisation more than integration.

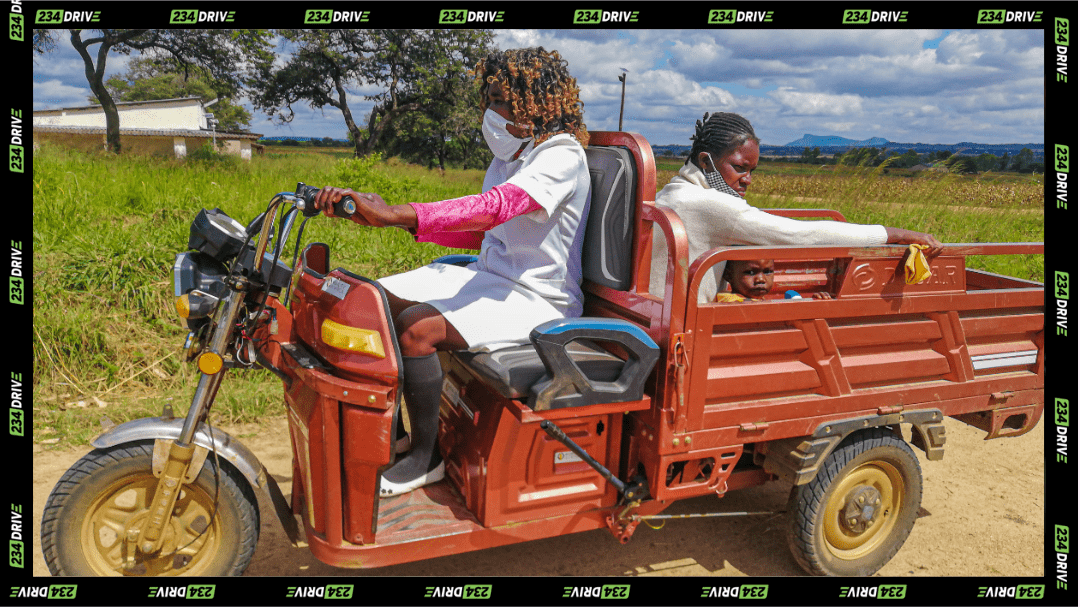

This pattern is familiar in Lagos (although Lagos has an organised body for road transport workers), Accra, Nairobi, and Kampala. Informal vans and motorcycles keep cities moving, but without reliable rail or formal buses, the result is fragile and costly.

Johannesburg’s experience points to five moves:

- Protect and rebuild core rail.

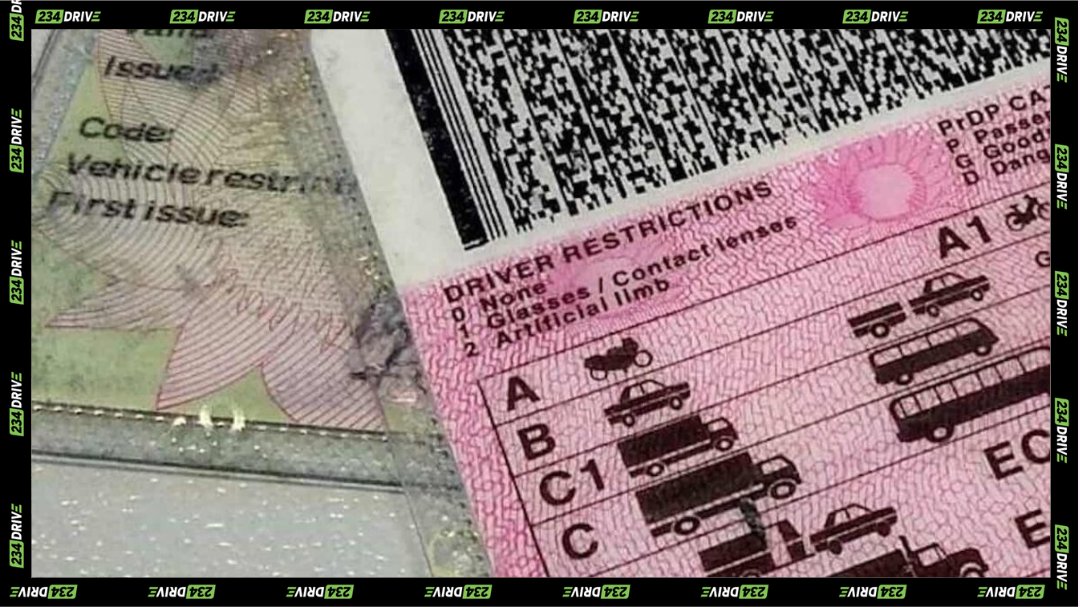

- Regulate taxi operations with clear route rights and enforceable safety standards

- Stabilise bus systems with ring-fenced funding and transparent contracts

- Integrate fares so riders choose speed and safety rather than only price

- Digitise payments to reduce cash conflicts and improve planning data.

This crisis is not about one bad operator. It is what happens when mass mobility leans on an atomised, cash-based system while rail decays and buses stall. Households pay more, trips take longer, and violence erupts over routes.

The fixes are not flashy, but they are proven: restore commuter rail and secure it, expand BRT with disciplined contracts, and bring taxi associations into a regulated, data-rich framework with real enforcement and fair economics.

For African cities, the choice is simple: fund a coherent network or keep paying in money, hours, and lives for a fragmented one. A world-class African city deserves a world-class timetable.

If your city could act this year, would you choose enforcement, integration, or rebuilding rail first?