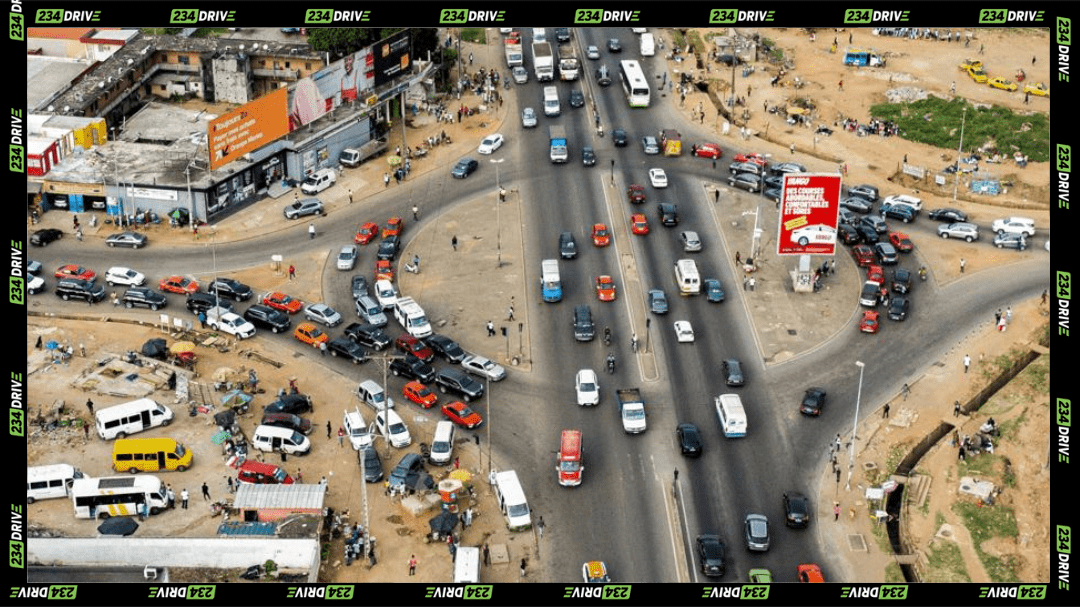

According to a WHO report in 2023, Nigeria tops Africa for road crash deaths at 21.4 per 100,000 people. This figure points to deep weaknesses in how mobility is organised, from road design and upkeep to safety management across the transport system.

Nigeria’s risk is shaped by infrastructure that wears down quickly. Potholes, broken signals, missing signs, and poor drainage make routine driving decisions harder. Rainfall exposes these weaknesses more sharply, with surfaces breaking apart and floods creating new hazards.

On the same roads, heavy trucks and fast-moving cars share space with motorcycles and pedestrians, often without barriers or safe crossings. Public transport adds to the strain, as minibuses and informal vehicles operate under pressure, with overloading and driver fatigue further heightening crash risk.

Enforcement is uneven, leaving many road hazards unchecked. Speeding, drink-driving, and non-use of seatbelts or helmets often pass without penalty. Vehicle inspections are inconsistent, allowing unsafe cars to remain in circulation.

Weak inspection standards and lax import controls add to the problem, introducing large numbers of substandard vehicles onto Nigerian roads. At the same time, training and licensing systems lack consistency, creating gaps in driver readiness—especially among commercial and heavy-duty drivers.

How Nigeria’s road accident and fatality rates compares with Europe’s

| Indicator | Nigeria | European Union |

| Death Rate (population-based) | 21.4 per 100,000 (2023) | ~44 per million (~4.4 per 100,000) (2024) |

| Annual Fatalities (recent year) | 5,421 deaths in 2024; rising trend in 2025 (1,593 deaths in Q1 2025) | ~19,800 deaths in 2024, -3% vs 2023 |

| Direction of Trend | Rising in 2025 (2.2% increase in fatalities first half 2025 vs 2024) | Gradual decline since 2023; 3% decrease in 2024 |

| Notable Practices | Intermittent enforcement; human factors like reckless driving, overloading, fatigue contribute | Data-led “Safe System,” Vision Zero pilots, automated enforcement; comprehensive road safety plans |

Source: WHO, EU Commission, Punch Newspaper

Nigeria’s figures show that a lot can be done: maintaining roads to consistent standards, protecting spaces for walking and cycling, scaling mass transit, setting stricter import rules to block substandard vehicles, and ensuring inspections remove unfit cars from circulation.

Combined with steady enforcement and stronger driver training, these steps could reduce the daily accident toll. The healthcare system also has a role—through faster emergency response, stronger trauma care, and rehabilitation support that lessens the long-term impact of crashes—while prevention must work to reduce the strain on hospitals in the first place.

If Nigeria confronts its mobility crisis with the same urgency shown in European counterparts, safer roads and better mobility frameworks remain achievable.