The cost of tokunbo cars in Nigeria has surged to unprecedented levels, reshaping the automotive market and forcing families to rethink vehicle ownership. Prices for popular models like the Toyota Corolla have jumped from around ₦1.9 million to as high as ₦9.5 million — a fourfold increase — driven by steep import tariffs, currency depreciation, and tighter trade policies both in the US and Nigeria.

Recent US automotive import tariffs, now set at 25%, have pushed up prices at American salvage auctions and wholesale markets. Since Nigeria’s used car market depends heavily on US exports, these increases have filtered directly into local prices. Meanwhile, Nigeria’s own import structure adds further pressure. Import duties, levies, and taxes can raise a vehicle’s cost by up to 50%, including the replacement of the 1% Comprehensive Import Supervision Scheme with a 4% Import Adjustment Tax. Combined with the weakening naira, this triple hit has made vehicle imports less viable for dealers and buyers alike.

Data from the National Bureau of Statistics shows an 83% drop in used car import value — from ₦819.15 billion in H1 2023 to just ₦138.62 billion in H1 2024 — with zero recorded imports in Q1 2024. Vehicle arrivals have also plunged from roughly 45,000 to 18,000 units. Dealers say funds that once bought 20 vehicles now barely secure five, creating a massive supply gap across the market.

For everyday Nigerians, the effect is immediate. Families are delaying purchases or settling for cheaper, riskier options — locally used vehicles with uncertain maintenance histories. In Lagos, where car ownership often substitutes for unreliable public transport, the price hikes deepen mobility inequality. As tokunbo cars slip out of reach, more commuters are pushed back into overcrowded, expensive public systems. Some relief has come from affordable Chinese models gaining adoption through government and bank fleets, but the transition remains slow.

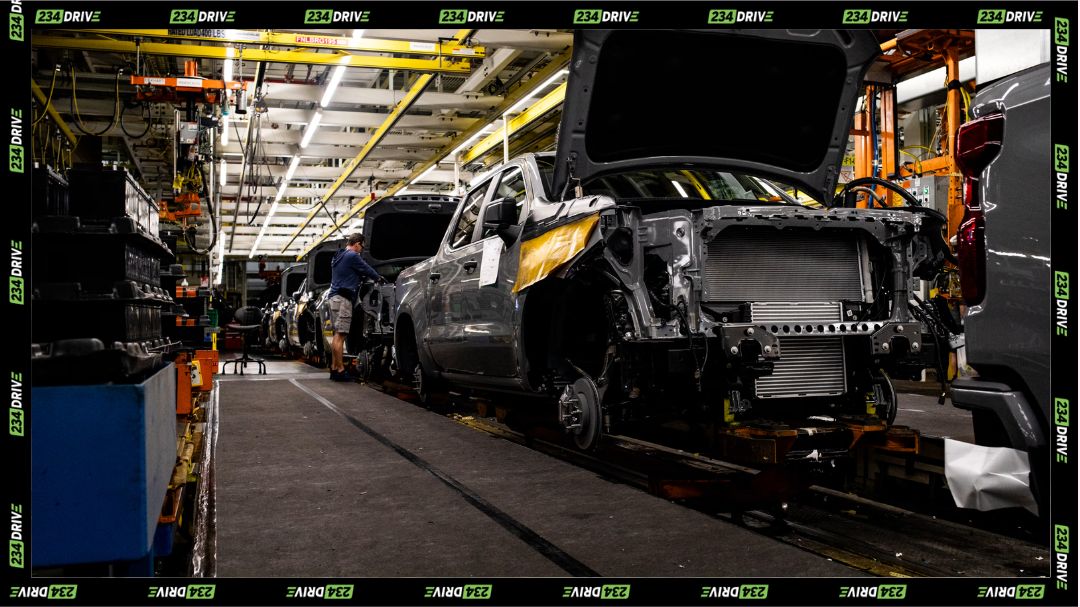

Nigeria remains one of the largest importers of used vehicles in Africa and ranks third globally, requiring around 720,000 cars annually. Local manufacturing, however, produces only about 14,000 vehicles a year — a fraction of demand. Without significant policy shifts to boost local assembly and stabilise the currency, experts warn that car ownership could soon become a luxury for the few.

This price spiral exposes a deeper question for policymakers: should Nigeria double down on import restrictions to protect local production, or prioritise accessibility for the millions who still depend on tokunbo cars for daily mobility?