Two days after Kenya unveiled its first locally branded electric vehicle lineup, the images flooding social media weren’t renders or concept sketches. They were metal, rubber, and sparks flying on a Nairobi stage.

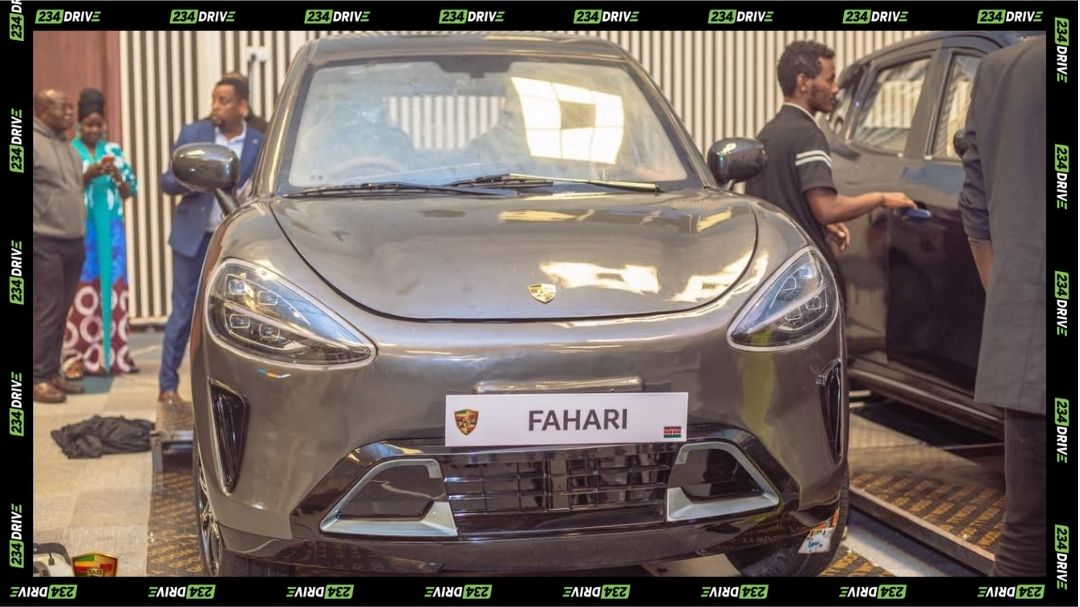

On 27–28 November 2025, Tad Motors launched four electric vehicles at The Edge Convention Centre: the Amani compact crossover, the Makena rugged SUV, Fahari and one yet to be named vehicle. The launch featured the silver-grey Amani and fire-red Makena side-by-side under ceremonial pyrotechnics, whilst a British racing green premium SUV—likely the Dhahabu variant or high-spec Makena—was unveiled separately. Principal Secretary Korir Sing’Oei tested the green model’s interior, and photos from the official Tad Motors account showed off-road tyres, roof rails, and angular LED lighting across the range. Each vehicle is priced between KSh 1.6 million and KSh 2.9 million, charges via a standard household socket, and delivers 250 km of range—specs aimed squarely at gig-economy drivers rather than luxury buyers.

Who builds, who powers, who manages

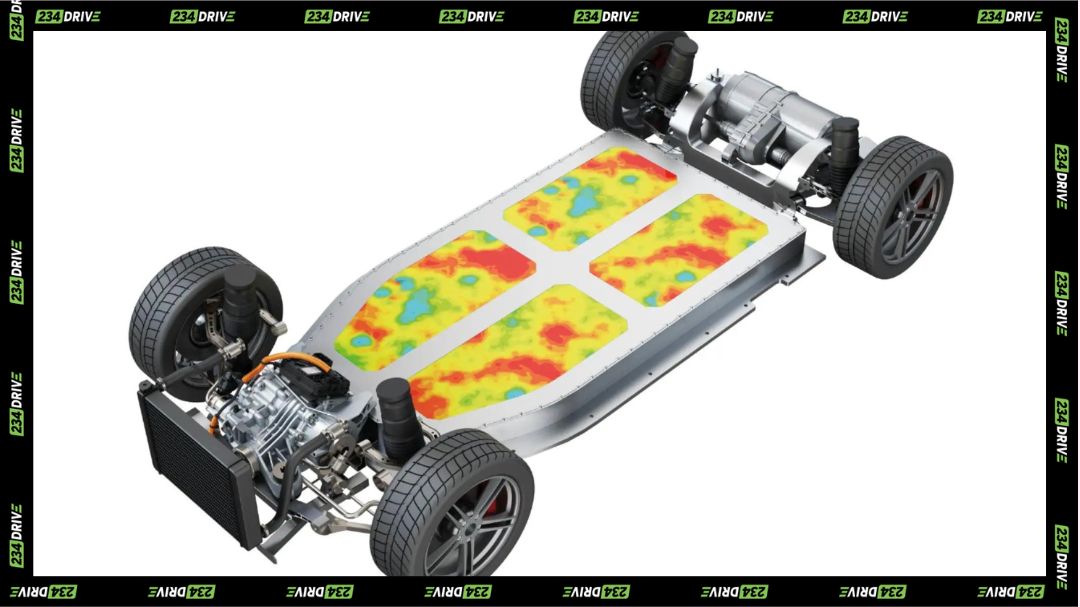

Tad Motors is the brand and integrator, assembling vehicles in Kenya using Chinese-sourced components and platforms. The government, through Principal Secretary Sing’Oei’s presence and policy backing, signals regulatory support and infrastructure alignment (charging networks, tax incentives). Manufacturing partners in China provide battery packs, motors, and chassis; Tad Motors handles final assembly, localisation, and go-to-market execution.

What This Signals About Kenya’s EV Strategy

This isn’t a pilot or a trial run. Launching four models simultaneously, with public officials inside the vehicles and pricing locked in, marks Kenya’s move from EV incentives to fleet-scale commercial operations. The government is betting on local assembly to create jobs, reduce import dependency, and position Kenya as East Africa’s EV manufacturing hub. Profitability hinges on volume: if Tad Motors can capture even a fraction of the ride-hailing and taxi market, it unlocks revenue streams that subsidised imports never could. The competitive edge isn’t technology—it’s price, proximity, and political backing.

How This Compares Globally

Rwanda launched its first locally assembled EV (Volkswagen e-Golf) in 2019, but production stalled after fewer than 50 units. South Africa’s automotive sector assembles electric models for export but hasn’t delivered an affordable, mass-market domestic brand. China’s BYD and Geely dominate African imports, but they’re foreign brands with tariff burdens. Tad Motors is attempting what no other Sub-Saharan country has scaled: a locally branded, competitively priced EV lineup deployed directly into commercial fleets. The gap between Kenya and its neighbours isn’t technology—it’s execution speed and government alignment.

How Fast Competitors Have Moved From Launch to Deployment

China’s NIO went from prototype unveiling to first deliveries in 18 months, clearing regulatory hurdles with state backing and pre-built charging infrastructure. Tesla’s Model 3 took roughly three years from reveal to volume production, though certification delays and factory ramp-up bottlenecks slowed rollout. Tad Motors hasn’t disclosed timelines for mass delivery, but if Kenya fast-tracks certification and leverages existing assembly facilities, the brand could have vehicles in commercial fleets by mid-2026. The advantage of using proven Chinese platforms is skipping the R&D phase—Tad Motors isn’t inventing batteries or motors, it’s integrating and branding them.

What Tad Motors Has Already Proven

The launch itself is the milestone. Tad Motors went from announcement to physical vehicles on stage in under a year, secured government endorsement, locked in pricing that undercuts imports, and attracted media coverage across East Africa. Revenue streams don’t exist yet, but the infrastructure does: assembly capacity, supplier agreements, and a clear target market (commercial drivers, not luxury buyers). Previous expansions in Kenya’s automotive sector—Volkswagen’s assembly plant, Toyota’s hybrid taxi rollout—took years to reach similar visibility. Tad Motors compressed that timeline by aligning with government EV policy and targeting a segment (affordable, practical electrics) where demand is proven but supply is scarce.

The Shift From Hype to Fleet-Scale Operations

Kenya’s EV sector has been stuck in the pilot phase for years—small trials, imported models, no local manufacturing. Tad Motors just ended that. Four models, public pricing, government officials inside the vehicles, and assembly starting in Nairobi means this is no longer a concept. The real test isn’t whether the cars work (they’re using established Chinese platforms), it’s whether Kenya’s infrastructure—charging networks, grid capacity, maintenance—can support thousands of EVs in daily commercial use. Should regulators treat locally assembled EVs as critical infrastructure to accelerate adoption, or let the market decide if demand justifies the rollout?