If you’ve ever listened in on a conversation with a Nigerian mechanic or roadside car dealer, chances are you’ve heard the phrase, ‘Na Direct Belgium’ offered as an assurance of quality. Heck, even global Afrobeats star Davido declares that he ‘go buy Belgium’ in his hit song Funds. I recently spent the past few months studying in the small country often described as ‘The Heart of Europe’, and whenever I told a Nigerian, the first thing they mentioned was not chocolate, waffles, or the European Union (EU) headquarters, but second-hand products—especially used cars.

The origins of this nickname are curious, but they open the door to a much bigger story: Belgium’s central role in Nigeria’s used car economy, the complex web of trade that ties both countries together, and the uncomfortable truth about how Africa is often treated as the final destination for the vehicles Europe no longer wants.

In the Beginning: Why Nigerians Call Used Cars ‘Belgium’

For decades, Nigerians have used ‘Belgium’ as a synonym for quality second-hand goods. According to Pulse Nigeria, the nickname took root in the 70s and 80s, when cheap production costs made Belgium a prime location for producing most of Europe’s products. Consequently, many of the second-hand clothes and other products that came into Nigeria were from Belgium. However, compared to other exporting regions, Belgium’s used goods were thought to be of higher quality.

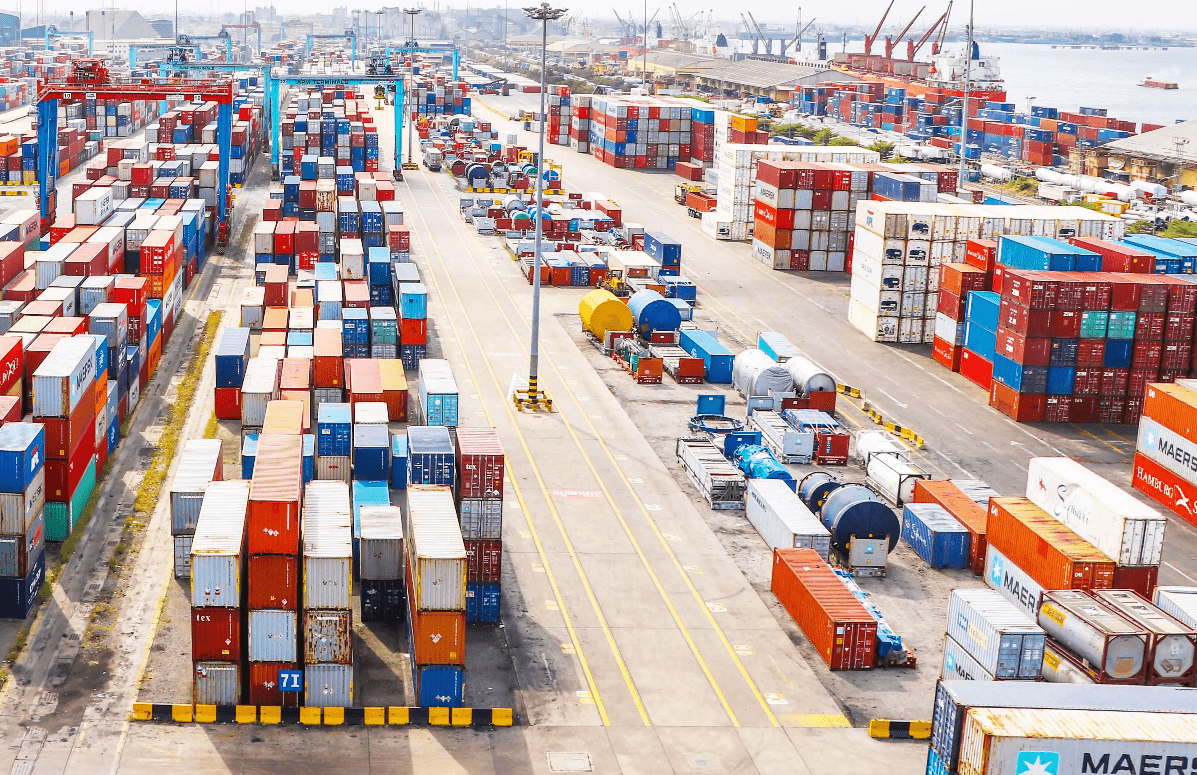

But in addition to that, Belgium’s central location in Europe also had a huge role to play. The Port of Antwerp, a major city in Belgium’s Flemish region, became an integral hub for exporting cars, electronics and other commodities from throughout Europe to Nigeria and Africa at large. In fact, when the Nigerian National Shipping Line (NNSL) was established in 1959, it was with the primary aim of acquiring a stake in the traffic between the port of Antwerp and the West Coast of Africa. Goods regularly ferried all the way from the Belgian port to Apapa in Lagos and Port Harcourt, as well as other West African cities like Abidjan and Dakar.

Back then, Belgian car dealers regularly put out ads in local newspapers. One of these was Euro-Auto’s Belgium sales advert of Mercedes, Datsun, Peugeot and Volvo cars with prices ranging from about £2,400 to £15,000 in a 1982 West Africa paper. Additionally, a 1992 report by Victor Morah revealed that over 85% of imported cars in the country were used cars, with a large chunk coming from the ‘the junkyards of Belgium, Germany and Holland’—the latter of which is now the Netherlands.

While those in western Nigeria called the used cars ‘Tokunbo’, the Yoruba name given to children who were born abroad, those in the East and other parts of the country called them ‘Belgium’ as a direct nod to their origins. As with ‘Danfo’ for yellow buses or ‘Okada’ for motorcycle taxis, the two monikers have stuck as efficient market shortcuts. But ‘Belgium’ is even more encompassing as it extends beyond cars to commodities of all sorts.

A Hub by Design

Nestled between the Netherlands, Germany and France, the Port of Antwerp—now the merged Port of Antwerp-Bruges—sits in the heart of Europe’s most industrialised belt. The country’s dense web of highways, inland waterways and rail links makes Belgium an effective middleman for EU exports. From Antwerp, German saloons, French hatchbacks, Dutch vans and other cargo are fed into deep sea vessels bound for West Africa. Thus, even if the vehicle starts its life in another European country, it lands in Nigeria with the ‘Belgium’ stamp of identity.

Nigeria’s car market has long been strongly skewed towards used car imports for reasons we’ve heard time and time again: the perpetually weakened Naira, high inflation rates, and the absence of mass-market locally assembled cars. According to a report by the UN, the number of used cars imported in Nigeria was 467,613—second only to Libya’s 791,918 and far ahead of Kenya’s 199,248.

Nigerian-used cars are looked down on in the market since cars shipped from Europe, even if old, are believed to have been better maintained due to stricter roadworthiness rules. More so, a Belgian-exported Toyota Corolla might have logged 200,000 km, but buyers would trust it more than one driven half the distance in Nigeria, where large poor road conditions easily chip away at cars’ lifespans.

Outside of Europe, Nigerian dealers also frequently turn to the US and Asia for their second-hand cars. In fact, from the same UN report, it was revealed that Europe’s share of the used vehicle export to Africa was the largest (45%), followed by Asia (34%) and the US (18%). Still, the current state of Nigeria’s economy means many youths cannot afford to buy a car, talk less of a Nigerian-used one.

The Dumping Ground Debate

As far back as 1990, major players in Nigeria’s Transport sector decried the import of vehicles from Europe via Belgium—and for very good reason. The argument then was that many of the used cars being imported had been phased out by their manufacturers, so much so that they no longer had available spare parts and could even ‘constitute death traps for the ignorant users’.

And now? The story has not changed much. In Europe, the 90s came with increased consciousness of the effect of car pollution on climate change and so, many Europeans sought ways to reduce their carbon footprint mobility-wise. For one, since 1st January 1993, the Euro 1 emission standards made fitting catalytic converters in new gasoline cars mandatory for all cars sold in the European Union (EU). But also, cars that were on the less ecofriendly side became more unappealing for the EU’s clean energy goals. Enter Africa, a perfect dumping ground for the cars that were too dirty to traverse European roads. Even more, Africa was more than happy to serve as a dumping ground, as long as the cars fit the bill and looked good enough.

When Europe amped up their auto decarbonisation efforts, after the Paris Agreement of 2016 and then the European Green Deal of 2020, the car jettisons to Africa became even more pronounced. The EU is on a mission to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050, so the fuel-guzzling cars? They’ve simply got to go.

But it goes beyond sustainability. The safety of the cars that are dumped in Africa has often been eroded by years of wear and tear.

In May 2025, the Nigeria Customs Service enforced a 10-year age limit on imported used cars. And before 2022, the limit was 15 years. Additionally, according to a 2020 report from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Nigeria had adopted Euro 3 emission standards for its imported used cars as of 2017. In contrast, the same UNEP report revealed that Kenya had adopted an age restriction of 8 years as well as the more stringent Euro 4 emission standards. This has resulted in the East African country having a much more modern and cleaner fleet than Nigeria’s. The results are also seen in the two countries’ road fatality rates: Kenya’s is 27.8 per 100,000 inhabitants while Nigeria’s is 29.5 per 100,000 inhabitants.

And worse, Nigeria and many other African countries barely have any checks in place to ensure the roadworthiness of these used vehicles. A Dutch inspection of 160 Africa-bound vehicles at the Port of Amsterdam found over 80% below Euro 4 emissions standard, many without valid roadworthiness certificates; one in eight airbags malfunctioned, and most diesel cars lacked particulate matter filters. Belgium’s flows are similar in profile since the Port of Antwerp-Bruges consolidates much of the same EU-sourced stock targeted at the same markets.

Hence, it’s no wonder that Africa has the highest number of road accidents than any other region in the world, as reported by The Brussels Times in 2020.

A Two-Way Trade Link

Unbeknownst to many, the trade relationship between Belgium and Nigeria is rather symbiotic. While Belgium exports thousands of vehicles to Nigeria each year, it also imports tonnes of crude oil from Nigeria yearly and sends back refined petroleum.

In fact, according to the Belgian Ambassador to Nigeria Pieter Leenknegt, ‘the bulk of the export from Belgium to Nigeria is refined petroleum’. Nigeria also exports semi-precious stones, fertiliser and cocoa to Belgium—yes, Nigerian beans are a big part of Belgian chocolate! Cocoa even overtook crude oil as Nigeria’s primary export to Belgium in 2024.

Still, Belgium has the upper hand in the trade relationship. In 2023, Belgium’s export to Nigeria stood at 4.8 billion EUR while Nigeria’s export to Belgium was only 277.84 million EUR. In the same year, Belgium declared plans to export cleaner fuels to Nigeria, following an incident in which a large consignment of petrol from Antwerp had to be returned in February 2022 due to dangerous levels of methanol.

Interestingly, the entrance of the Dangote Petroleum Refinery into the Nigerian market poses a significant threat to the crude-petroleum trade link between Belgium and Nigeria. And Belgium knows it. In an interview with PREMIUM TIMES in August, Leenknegt projected that the refinery’s operations would start to leave a mark on the bilateral trade by the end of 2025—what he described as ‘the Dangote Refinery effect’. Consequently, Leenknegt emphasised the need for the two countries to expand their trade with regards to other products, particularly in the agriculture and health sectors.

Dangote Petroleum Refinery. Source: unmaskng

Raising the Standard

The Belgium car trade reflects both opportunity and risk. For Nigerians, it has long provided an affordable path to car ownership in a country where brand new cars are out of reach for most. For Belgium, it has been a convenient outlet for vehicles aging out of Euro standards. But the bargain comes with costs: dirty fuels, unsafe cars, and a public health burden carried by African cities.

Nigeria does not need to abandon used-car imports, but it does need to set stricter entry standards and actually enforce them. Belgium and other European exporters also have a responsibility to apply the same roadworthiness checks for exported cars as they do at home.

If trade rules are enforced consistently on both ends, ‘Na Direct Belgium’ could become more than a shallow sales pitch. It could mean a car that is genuinely safe, reliable, and cleaner—something worth the trust Nigerians have placed in that name for decades.