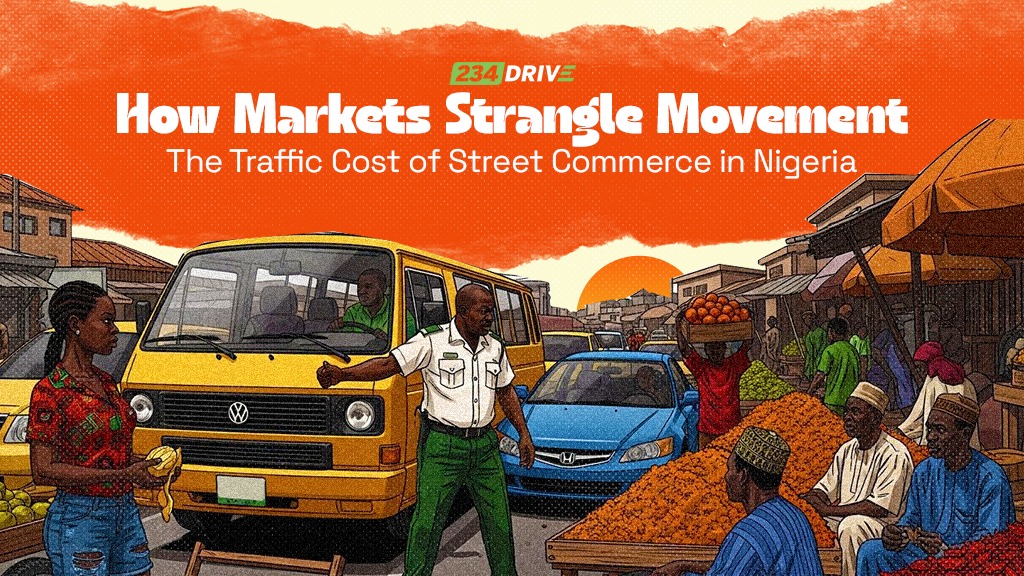

7:47 AM — The Driver

Kunle’s blue Honda has moved exactly four car lengths in the past twenty minutes. The Oju Ore junction, normally a 90-second passage, has now become a parking lot. Through his windshield, he can see the problem: vendors had claimed both sides of the road, their displays creeping 1.5 metres into what should be traffic lanes. A woman selling plantains has positioned her table at the exact point where vehicles need to turn. Three bus conductors are haggling with a NURTW personnel in the middle of the lane. A bus can’t pull to its designated stop because a cluster of fruit sellers have occupied the bay. Cars squeeze into a single lane where there should be two. His dashboard clock flashes 7:48 AM. His meeting starts at 9:00 AM in Atan, one hundred and twenty seven kilometers away.

12:15 PM — The Pedestrian

Nenye needs to cross to the other side of the Ogba junction. The pedestrian walkway—theoretically 1.8 metres wide—has been reduced to a 40-centimetre corridor between vendor stalls. She steps off the curb onto the road because there is simply no walking space left. Cars honk. An okada swerves. She presses herself against a table of secondhand shoes as a danfo barrels past, its side mirror missing her shoulder by centimeters. She hisses. On the other side, she’ll need to navigate another gauntlet of stalls, dodge customers examining ‘bend-down-select’ clothes, and somehow cross back through two lanes of barely moving traffic. What should be a two-minute walk will take fifteen. Yesterday, a woman was hit trying to make this same crossing. The woman survived. Many don’t.

6:25 PM — The Trader

Mummy Atikah has been at this spot since 5:30 PM. She pays N200 daily to the area boys who control this section of roadside. Her plantain display extends exactly where evening traffic converges—prime location. She knows she’s blocking the road. Everyone knows. But the alternative is a formal market stall in Ajah for N500,000 annually. Her entire inventory—three bunches of plantains, a stack of yams, a basin of tomatoes—costs N22,000. It’s a no-brainer. She stays on the road. The cars can wait. In fact, the cars will wait… it’s Lekki-Epe afterall. At least, they’ll buy a bunch of plantains or two from her while waiting.

Buckle Up, It’s Gridlock Time

Lagos has about 7,600 kilometres of roads attempting to serve approximately 1.2 million registered vehicles and over 24 million people. Official transport assessments indicate that the road network density is about 0.4 km per 1,000 people, which is low even by African megacity standards, while daily travel demand exceeds 20 million trips across all modes.

The infrastructure deficit is severe enough without additional complications. But street markets don’t merely coexist with this overburdened system—they actively degrade it.

Research documenting the traffic impact of street trading in Lagos opens our eyes to a pattern of consistent obstruction. Vendors displaying goods along busy roads and intersections encroach onto roadways by 1 to 1.5 metres or more. This may seem modest until you calculate the cumulative effect across multiple vendors lining both sides of a corridor. A road designed with a 10-metre carriageway effectively operates at 7 metres. Three lanes become two. Two become one. Traffic flow deteriorates inevitably.

At Igando bus stop, traffic surveys conducted during periods of heavy street trading activity versus periods without traders, documented dramatic differences in vehicle throughput. The presence of traders and the illegal parking they generate caused measurable delays and increased accident risk. Similar studies at Idumota and Balogun Markets showed that market-related activity—loading and offloading, customers parking on roadsides, vendors occupying traffic lanes—directly correlates with traffic flow.

The Lagos State Traffic Management Authority (LASTMA) has repeatedly identified street trading as a primary congestion factor. Director of Public Affairs Adebayo Taofiq stated that street trading, roadside markets, and indiscriminate loading and offloading of goods, especially during peak hours, encroach upon active roadways and significantly reduce carriageway capacity. The agency’s reports note that congestion at Offin Canal Market and Olowogbowo, at Egbeda along the Idimu-Isheri Road corridor due to ram trading, and along Broad Street approaching Apongbon are all directly tied to market activities obstructing traffic flow.

We actually see this play out in real time; commuters in Lagos spend a minimum of three hours daily in traffic. Some estimates suggest residents collectively lose 14.1 million hours every day to gridlock. Six man-hours are lost per person daily due to traffic congestion resulting from poor road infrastructure compounded by obstruction. The economic cost is tremendous: fuel burned while idling, appointments missed, business opportunities lost, emergency vehicles unable to reach their destinations, we could go on and on.

When Infrastructure Meets Informality

From an urban design perspective, street markets represent a fundamental mismatch between planned capacity and actual usage. Roads are designed with specific load-bearing capacities, lane widths, and drainage systems calibrated to their intended function. When that function is hijacked for a purpose the infrastructure was never meant to serve, the system fails.

Let’s look at drainage: Lagos’s storm drainage network, already inadequate for the city’s needs, assumes that roads will be roads—hard surfaces designed to channel water into gutters and eventually into larger drainage systems. Street markets generate organic waste, packaging materials, and general refuse at volumes the system cannot absorb. Femi, a LAWMA field supervisor, described clearing waste traders drop everywhere daily, noting that these locations lack bins or waste collection points since they were not intended as markets.

As the environmental officer Godwin Agholor described it: waste dumped into drainage, movement chaos, worsening flooding, and rising pollution—everything connected. When rains come to Lagos, blocked drainage systems overflow. Streets flood. Traffic halts completely. The market-induced blockage doesn’t merely slow traffic; its ripple effect can stop an entire city.

Air pollution adds to the problem. Lagos’s air quality already exceeds World Health Organisation recommended limits by a factor of five. Vehicles navigating congested market areas idle longer, burn more fuel, and emit more pollutants. The fatal accident rate in Lagos stands at 28 per 100,000 people—three times greater than most European cities. Street vendors account for 15 percent of pedestrian fatalities, as traders force pedestrians onto roadways where they’re struck by vehicles.

A two-lane road with vendors on both sides becomes a single-lane passage where vehicles must wait for oncoming traffic to clear before proceeding, a regular occurrence in places like Agege and Ogba.

Pedestrian walkways designed for continuous flow become obstacle courses requiring pedestrians to step into traffic. Bus stops designed as brief pause points become extended marketplaces where buses cannot access their designated bays, forcing passengers to board from the street. Emergency vehicles—ambulances, fire trucks—cannot navigate these constricted corridors at all.

According to Dotun*, a senior officer at the Lagos State Ministry of Physical Planning, uncontrolled trading weakens the entire urban system, obstructs roadways, impedes emergency response, and makes the city extremely difficult to manage. This is not hyperbole, it is our reality.

The Oshodi Case Study: Clearance as Infrastructure Reclamation

Before 2016, Oshodi Market represented the extreme endpoint of market-induced traffic dysfunction. One of Lagos’s most critical transport interchanges, handling over 200,000 daily commuters, had been consumed by informal trading. Vendors set up in passenger movement areas, on rail tracks, across roadways. Traffic was paralysed for hours.

The Lagos State Government’s response was comprehensive demolition. In January 2016, authorities cleared the old Oshodi Market and rebuilt it as an organised transport hub with dedicated terminals, pedestrian bridges, and traffic management. The government had previously commissioned Isopakodowo Market in 2014, offering traders stalls at N5,000 annually—extraordinarily subsidised. The immediate aftermath showed promise—traffic improved, the transport function was partially restored. But nearly a decade later, Oshodi reveals why clearance alone doesn’t solve the problem.

Street traders have returned. In December 2024, authorities cleared vendors operating on rail tracks at Bolade, opposite Arena Shopping Complex, after viral videos showed people buying and selling perilously close to moving trains. In July and September 2024, enforcement operations removed illegal traders from highways, roadsides, and railway tracks across Oshodi. As of 2024, the Lagos State government arrested an average of 50 street traders daily, with Oshodi remaining a persistent hotspot. Each clearance temporarily restores order, then the vendors return.

The pedestrian infrastructure has failed spectacularly. In January 2025, the government closed the main pedestrian bridge connecting Terminals 2 and 3 due to safety and structural integrity concerns—the bridge was reportedly shaking under user weight. This forced all pedestrian traffic onto a single alternative bridge, creating dangerous overcrowding.

Commuters reported spending over 20 minutes just to cross, with viral videos showing crowds comparable to ‘bumper-to-bumper’ traffic jams.

Theft increased. Miscreants extorted money from trapped pedestrians. The congestion became so severe it sparked public outcry and government promises to “make available additional bridges”. The infrastructure built to solve mobility problems has proven inadequate for actual demand. The bridges cannot handle the volume of people moving through Oshodi daily. And the side markets have returned—not at 2015 scale, but persistently enough that enforcement operations occur monthly.

This suggests that there is a core failure. Clearing a market doesn’t eliminate the economic pressure that created it. Building infrastructure doesn’t solve mobility if that infrastructure is insufficient or poorly designed for actual usage. Oshodi is better than 2015, but it remains dysfunctional—a cautionary tale about interventions that address symptoms without solving root causes.

Just recently, on 20th December, 2025, Lagos State Commissioner for Environment and Water Resources Tokunbo Wahab announced joint enforcement operations aimed at achieving a cleaner Lagos at Ikotun Main Market, Igando Market, and other roadside markets along the Ikotun-Igando Road. This clearance dislodged traders who had encroached on road setbacks and walkways. The Lagos State Government has also conducted clearances at Lakowe corridor, Ikorodu roundabout, Abule Egba, Oyingbo, Mile 2 at 2nd Rainbow Junction, and Iyana Ipaja repeatedly. The results? Each operation temporarily restores traffic flow. Each time, the markets gradually reestablish themselves.

The Economic Paradox

About 5.5 million people work in Lagos’s informal economy—approximately three-quarters of the workforce. For these workers, street vending offers immediate cash flow without overhead, no boss to report to, and no credential requirements. However, this freedom is not a luxury but a survival strategy in an economy with few formal jobs and high inflation.

Yet, this survival strategy extracts a collective cost. Every vendor claiming 1.5 metres of road space reduces traffic capacity. Every customer stopping to make a purchase adds a parked vehicle to an already congested corridor. Every waste item thrown into a drain increases flood risk. Every pedestrian forced onto the roadway increases accident probability.

Economists call this a tragedy of the commons. No single vendor causes gridlock. But thousands of vendors, each making what is relatively rational economic choice, collectively paralyse urban mobility. And because the cost is distributed across millions of commuters while the benefit accrues directly to individual vendors, the behaviour persists.

Enforcement attempts to correct this imbalance through punishment—fines, arrests, confiscation of goods.

Chief Superintendent of Police (CSP) Shola Adetayo Akerele’s warning emphasised both legal and safety risks, noting that brake failure or vehicle accidents can happen at any time to roadside traders. The Lagos State Environmental and Special Offences Taskforce has made this argument repeatedly: trading on the road risks your life, creates legal liability, and ultimately costs more than renting proper space.

Nonetheless, far-sightedness is in itself a form of privilege. For most of these traders, all they can see is how they can make some income to tide them over day by day. Funmi, a mother of three, whom I spoke with is one of such traders. She arrives at Iju-Ishaga Junction every day at 8AM to sell used appliances, operating without a shop and taking home cash every day, but the amounts are modest. A vendor earning N3,000-N5,000 daily (roughly $2-3 USD) would need to save every naira for two to three weeks just to afford the cheapest annual stall rental. But vendors can’t save every naira—they must eat, pay rent, send children to school, restock inventory. It simply doesn’t work. The sidewalk, by contrast, costs nothing beyond occasional bribes to officials and the physical toll of constant harassment and relocation.

John, who sells used shoes at Iju-Ishaga, articulated the struggle: “Upon all the money we have in this country, the poor masses are still suffering. If there are jobs in this country, you won’t find me here selling okrika shoes. I have three children in school; this is how I make money to train them”.

The tale of Arena Market in Oshodi further emphasises the reality of formal markets; completed in 2009 with 3,000 stalls, parking for over 1,000 vehicles, restaurants, banking halls, and modern facilities, the complex remains largely unoccupied more than a decade later. Lock-up shops rent for N300,000 annually while open stalls cost N55,000. Vendors like Funmi can only dream of renting one of these stalls. And survival doesn’t leave room for dreaming, only practicality.

The Global Context: Markets and Mobility Worldwide

Lagos’s street market-traffic conflict is not unique. It’s a pattern observable across rapidly urbanising cities in the Global South where formal employment cannot absorb labor supply and where infrastructure lags population growth.

India has 16.5 million workers as market traders and street vendors nationally. In Senegal, market traders and street vendors comprise 24 percent of total employment and 52 percent in Dakar—meaning more than half the capital’s workforce would be displaced by comprehensive street vending elimination. Bangkok’s street vendor population surged after the 1997 financial crisis as laid-off workers used business skills from the formal sector to operate street vending businesses, with a new generation of educated vendors clustering near mass transit stations. Where rapid urbanisation meets inadequate formal employment, street vending proliferates. And where street vending proliferates near transport nodes, traffic suffers.

Cities that successfully manage this tension share characteristics: infrastructure investment before enforcement, vendor participation in planning, and integrated approaches treating markets and transit as complementary rather than competing.

The Link to Global Development Goals

The friction between markets and mobility connects directly to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. Target 11.2 calls for providing access to safe, affordable, accessible, and sustainable transport systems for all by 2030.

Street markets that obstruct walkways, force pedestrians onto roadways, and block bus stops advertently undermine this target. When 15 percent of Lagos’s pedestrian fatalities involve street vendors, when commuters lose 14.1 million hours daily to gridlock, when emergency vehicles cannot navigate congested corridors, the transport system has failed its basic function.

But SDG 11 also includes Target 11.1 on adequate housing and basic services and Target 11.3 on inclusive urbanisation. For the 5.5 million Lagos residents working in the informal economy, many of them street vendors, these markets represent economic survival. Nearly 1.1 billion people globally lived in slums in 2022, with another 2 billion expected over the next 30 years. For many, street vending is their economic foothold in cities.

This suggests that the solution requires advancing multiple goals simultaneously rather than privileging mobility over economics or vice versa. Markets that respect pedestrian flow, maintain emergency access, and operate within spatial parameters can coexist with functional transport systems. Markets that spread uncontrolled undermine urban functionality for everyone, vendors included.

Women comprise the majority of street vendors in many countries—83 percent in Ghana, 68 percent in Peru, 67 percent in El Salvador. Policies that eliminate street vending without alternatives therefore have significant gender equity implications, connecting to SDG 5. The health impacts of traffic congestion—air pollution, accident rates, stress—relate to SDG 3. The economic disruption from gridlock affects poverty reduction (SDG 1) and economic growth (SDG 8).

Female street traders. | Source: Kobina via Pinterest

Sustainable mobility is a lot more than just developing infrastructure. It is about controlling the public environment around the infrastructure so that it can perform as intended.

Design Solutions That Acknowledge Reality

If street markets cannot be eliminated through enforcement alone—and fifteen years of evidence suggests they cannot—then the design question becomes: how do you accommodate commerce without sacrificing mobility?

Several approaches exist internationally:

- Designated Vending Zones with Spatial Requirements: Thailand’s Bangkok has established rules requiring vendors to ensure 1.5 to 2 metres of pedestrian walking space, limiting each stall to three square metres, and mandating emergency exits every 10 stalls. The regulations acknowledge that vending will occur and attempt to structure it. Bangkok has also pursued vendor removals—around 10,000 in the past two years—while establishing hawker centers as alternatives. The model combines accommodation in some areas with strict enforcement in critical corridors.

- Time-Limited Vending: Some cities allow markets during off-peak hours when pedestrian and vehicle traffic is lighter, then require clearance during rush periods. This reduces conflict between commerce and commuter flow without eliminating the economic activity entirely.

- Integrated Market-Transit Infrastructure: Rather than treating markets and transit as competing uses, design could acknowledge their co-location. New BRT stations, rail terminals, and major bus stops could include adjacent flexible vending zones with:

- Modular stall infrastructure rented hourly via mobile payment

- Integrated waste collection systems

- Clearly marked pedestrian corridors with enforced minimum widths

- Weather protection and lighting

- Defined traffic lanes that vendors cannot encroach upon

The capital cost would be substantial, but likely less than the cumulative economic cost of gridlock and the ongoing cost of enforcement operations that ultimately fail. And unlike traditional enclosed markets, these zones would maintain the location advantage—proximity to commuter flows—that makes street vending economically viable.

The Technology Question

Mobile payment adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa has been dramatic. Kenya’s M-Pesa reaches 90 percent of adults. Nigeria’s PalmPay grew from 10 million to 25 million users in less than a year. In South Africa, Street Wallet provides QR code lanyard cards to street vendors, allowing customers to pay via Apple Pay, Samsung Pay, or other platforms without vendors needing smartphones or bank accounts.

For individual vendors, digital payments reduce theft risk, create transaction records, and expand the potential customer base. But technology cannot solve the fundamental spatial problem. A vendor with a mobile payment terminal still occupies the same 1.5 metres of roadway, still blocks the same drainage grate, still contributes to the same pedestrian congestion.

The real technological opportunity lies in managing the collective spatial problem. Imagine an app where vendors bid for specific locations based on real-time demand, where enforcement can see which vendors have permits, where commuters can see traffic flow and choose routes accordingly, and where urban planners can analyse where vending clusters form and adjust infrastructure accordingly. This is theoretically possible with existing technology. It however requires political will, substantial capital investment, and a fundamental shift from viewing street vending as an illegal activity to be eliminated rather than an economic reality to be managed.

Toward Managed Coexistence

After fifteen years of enforcement operations that temporarily clear vendors only to see them return within weeks, the more pertinent question the authorities should be asking is, how do we make street markets work without strangling traffic and risking lives in the process?

This means getting genuinely strategic about where enforcement really matters and where accommodation might be the wiser choice. Emergency routes, major arterial roads, and locations with documented safety risks—these corridors need firm, sustained enforcement action because the stakes are simply too high. But here’s the part that keeps getting missed in every intervention: enforcement only produces lasting results when there’s somewhere else for vendors to go, and not just a theoretical somewhere that exists in a planning document. Not “we’re planning a market that will be ready in 2027” but actual, functioning alternatives that make economic sense for vendors operating on tight margins. Otherwise, the city is just playing an expensive, exhausting game of musical chairs where the music never stops and everyone involved grows increasingly frustrated.

When the government builds a new BRT station and vendors materialise around it within weeks like clockwork, is anyone at this point genuinely surprised? Maybe it’s time to plan for this inevitability from the beginning rather than acting shocked each time the pattern repeats itself. New transport infrastructure could include designated vending zones from day one—properly designed spaces with basic infrastructure like lighting, waste collection, and clearly marked pedestrian lanes that are actually wide enough for people to walk through. This approach involves acknowledging reality and working with it, which might prove far more productive than the current strategy of perpetual surprise and reaction.

Digital permit systems offer a practical middle ground that could benefit everyone involved in this daily negotiation of space. Vendors register for specific locations and time slots via mobile money platforms that many already use for other transactions, enforcement officers verify permits instantly via smartphone applications, and everyone operates with clear knowledge of the rules and boundaries. Those who comply get to operate legally without harassment, while those who violate the terms face actual, consistent consequences.

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: policies designed without meaningful input from actual vendors would fail spectacularly because planners, despite their expertise and good intentions, don’t always understand how the informal economy actually operates on the ground level. A vendor association can explain in minutes why a seemingly perfect formal market will sit half-empty while roadside trade continues to thrive just blocks away—they understand customer flow patterns, pricing dynamics, and operational realities that don’t always appear in planning documents. Their insights aren’t optional nice-to-haves for the sake of inclusion; they’re operationally essential for designing interventions that actually work. Nobody knows street vending better than the people who do it every single day.

Remember The Pedestrian, The Driver and The Trader from the start of this story? All three of their perspectives are valid and important, all three people’s needs matter, and the real challenge is designing systems where they can coexist in the same space without anyone getting crushed—economically or literally—in the process.

Meanwhile, life continues its daily pattern: the plantains remain displayed on the roadside each morning, the traffic remains largely stationary during peak hours, the pedestrian keeps dodging danfos and okadas while trying to reach the other side. And everyone involved in this complicated urban ecosystem keeps showing up each day to navigate this intricate dance of survival and circulation. What is genuinely needed is a pragmatic evolution; policies that work with human behavior and economic realities rather than against them, infrastructure that accommodates the city as it actually functions rather than ignoring inconvenient patterns, and solutions carefully designed for the cities in Nigeria.

After all, the junction isn’t going anywhere, and neither are the people trying to make a living at it, the commuters trying to pass through it, or the pedestrians trying to navigate around it. The real question facing us is whether the cities can find genuinely workable ways for all these people to occupy the same contested space without the result being perpetual gridlock—both on the roads themselves and, perhaps more importantly, in the policy thinking that determines how the city responds to these enduring challenges of rapid urbanisation and economic necessity.

*Name changed to preserve anonymity