A Chinese electric mobility firm just made Kenya’s boldest bet on clean transport look a lot more tangible. MojaEv handed over 30 Neta V electric vehicles to taxi operators in Nairobi, marking one of the largest single-day EV releases the country has seen since the sector’s initial push began. Five of those units went to County Bus Services Limited, with the rest distributed among taxi firms eager to slash fuel bills and tap into the ride-hailing economy. This isn’t just a symbolic gestureit’s a calculated move to prove that electric taxis can survive Kenya’s urban grind while turning a profit.

The Neta V, manufactured by Hozon Auto, is a compact electric SUV built specifically for high-mileage commercial use. It packs a 40.7 kWh lithium-ion battery that delivers roughly 300 kilometers of real-world range, enough for a full day of city driving without needing a mid-shift recharge. The vehicle hits a top speed of 101 km/h and can accelerate from 0 to 50 km/h in under 3.9 seconds specs that matter when you’re weaving through Nairobi traffic or chasing ride requests. Charging takes about eight hours on AC power, and the 95 PS motor generates 150 Nm of torque, keeping pace with the stop-and-go rhythm of taxi work. Inside, drivers get a 14.6-inch touchscreen that integrates seamlessly with ride-hailing platforms like Uber and Bolt, allowing them to manage routes, pickups, and earnings without bolting on extra hardware. The vehicle’s 335-liter boot space handles luggage comfortably, and its quiet cabin has reportedly improved passenger satisfaction leading to better tips and repeat business, according to driver testimonials.

MojaEv builds the business case around deployment, not just hardware. The company sources vehicles from China, arranges leasing options through partners like Caritas Bank, and ensures integration with digital mobility providers so drivers can start earning immediately. County Bus Services and other recipients highlighted cost savings as the primary draw. Sylvia Saita, representing the firm, noted that switching to EVs strengthened operations while supporting environmental goals. Across Kenya, taxi drivers like Paul Mwai have reported monthly fuel savings approaching $700translating to 40-70% reductions compared to gasoline vehicles. Lower maintenance costs add to the equation, with fewer moving parts and no oil changes required. For drivers operating on thin margins, these savings mean the difference between scraping by and reinvesting in family needs or fleet expansion.

This delivery plugs directly into Kenya’s national target of achieving 5% electric vehicle penetration among new registrations by the end of 2025. With annual vehicle imports hovering around 100,000 to 150,000 units, hitting that benchmark means registering approximately 5,000 to 7,500 new EVs per year. As of late 2024, the country had an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 EVs on the road, mostly e-motorcycles and taxis, with over 200 units deployed in the taxi and ride-hailing segment alone. MojaEv has already contributed more than 100 vehicles to that count. The government is backing the push with tax exemptions and finance bill incentives designed to lower upfront costs, though infrastructure gaps and high initial pricing remain persistent barriers. The pace is promising but not yet explosivereaching 5% will require sustained coordination between private operators, policymakers, and infrastructure developers.

MojaEv’s broader strategy extends beyond taxis. The company plans to deploy 30 electric buses for Kenya’s matatu sectorthe sprawling network of public minibuses that moves millions daily. More ambitiously, an assembly plant is scheduled to open in Mombasa by January 2026, starting with semi-knocked-down units and scaling to complete-knocked-down production. The facility aims to produce 3,000 to 5,000 units annually, potentially creating 4,000 to 6,000 jobs while reducing reliance on fully imported vehicles. CEO Wang Aiping has emphasized addressing critical pain points like charging infrastructure and spare parts availability, recognizing that long-term viability depends on solving logistical bottlenecks, not just selling vehicles.

How does this compare globally? China’s EV taxi fleets in cities like Shenzhen transitioned almost entirely to electric within five years, driven by aggressive subsidies and mandated phase-outs of combustion engines. India’s push for electric rickshaws and cabs has been slower, constrained by inconsistent policy support and fragmented charging networks. Kenya’s approach sits somewhere in between less coercive than China’s, but more focused than India’s scattered initiatives. The advantage here is scale testing: commercial fleets like taxis absorb technology risks faster than individual buyers, generating real-world data on durability, charging behavior, and profitability that can inform broader adoption.

MojaEv’s delivery also signals a shift from pilot projects to fleet-scale operations. Early EV efforts in Kenya often stalled at the demonstration phase; a few vehicles rolled out for photo ops, then quietly disappeared. This handover, combined with ongoing deployments by competitors like BasiGo in the bus sector, suggests the market is moving past proof-of-concept. The question now is whether infrastructure can keep pace. Charging stations remain scarce outside major urban centers, and grid reliability is uneven. Without a denser network of fast chargers and trained technicians, even the most reliable EVs risk sitting idle when breakdowns occur or batteries need servicing.

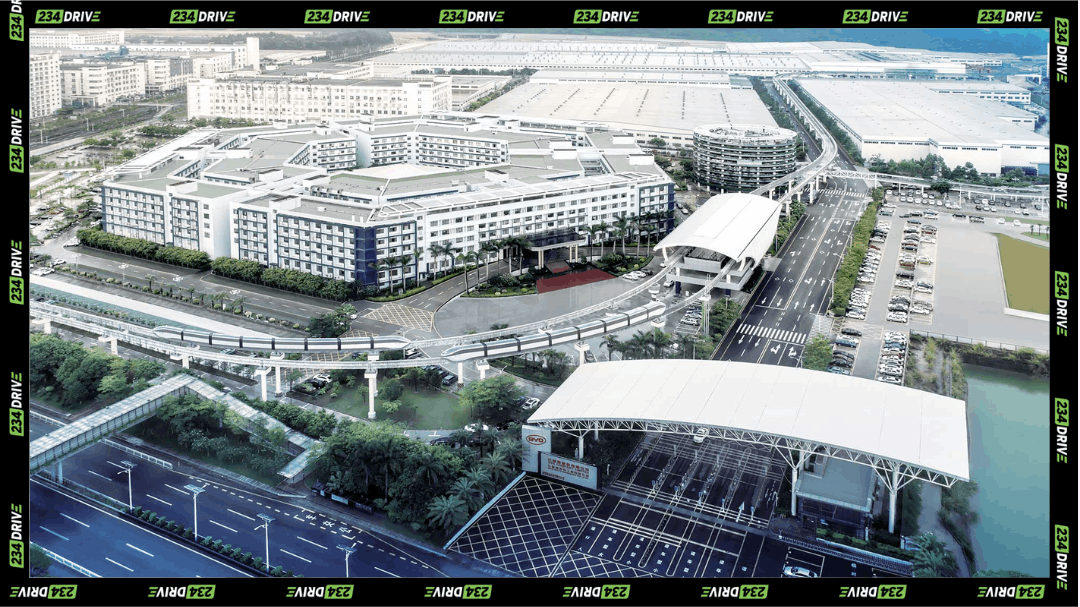

The event itself captured the momentum visually rows of white Neta V vehicles lined up with ribbons, surrounded by drivers, company reps, and government stakeholders. It’s the kind of scene that turns abstract climate goals into something you can touch and drive. But optics aside, the real test is what happens over the next 12 months. Can these 30 vehicles clock enough kilometers and generate enough savings to convince the next wave of operators to make the switch? Will Kenya’s import rules and incentive structures hold steady, or will policy shifts disrupt the trajectory?

Kenya’s path to 5% EV adoption hinges on whether initiatives like MojaEv’s can scale without relying entirely on foreign imports. Local assembly would reduce costs and build technical capacity, but it requires sustained investment and demand certainty. If taxi fleets prove the economics work, private buyers might follow. If not, Kenya risks becoming another market where EVs remain confined to niche applications while combustion engines dominate for another decade. The clock is ticking, and 2025 is closer than it looks.