There was a time when the radio was the heartbeat of the road. You turned the key in the ignition, and the first sound wasn’t the engine; it was the voice of the morning show host, the opening notes of a song you didn’t know you needed, and the static that meant you were too far from home.

For many millennials, radio was as much a part of the commute as the steering wheel. It was there in the back seat of school runs, in the danfo rides to Ojuelegba, and in the long drives on the Lagos–Ibadan expressway. Gen Z’s might remember it too—maybe not as fondly—but they know the feeling of tuning the dial to beat silence when there seemed to be nothing else to listen to.

Radio wasn’t just entertainment. It was a companion. Morning hosts had nicknames you could shout in traffic. Call-in shows turned strangers into road trip friends. Sports commentators kept okada riders glued to match updates, while gospel programmes on Sunday mornings softened the Naija hustle for a while.

It was also practical. Long before Google Maps could guide you, radio hosts would warn listeners to avoid the Third Mainland Bridge because “traffic don choke from Oworonshoki.” In a city where congestion is a way of life, the radio was a real-time guide.

For those of us who grew up with it, the intimacy went beyond information. When I was younger, I tuned in at 10 PM to a station I can’t remember. They recommended songs for different days, and you could call in to hear your request played. On other nights, another station ran relationship advice shows, where listeners shared their stories—happy, sad, and complicated—and received counsel live on air. These were moments that made radio feel alive, personal, and deeply woven into daily life.

Who’s Still Listening?

The truth? Not as many people as before. Bus drivers, once loyal to their favourite FM stations, now plug their phones into portable speakers and blast DJ YK mule mixes or street hits from Boomplay, an Africa-focused streaming platform. 9-to-5 commuters who once tuned in for breakfast shows now queue up podcasts or curated playlists before they even leave home.

Behind the mic, radio professionals have seen these shifts firsthand. However, Hyeladzira, a radio journalist with five years’ experience, says the decline in listeners isn’t as drastic as people assume. “It was central to passing information and keeping people up to date. It still is,” she noted, “and I’m forever fascinated by traffic radio in Lagos; what do you mean there’s a station whose entire job is to talk about traffic and keep people company when they’re stuck?”

Morning shows blending news, current affairs, and entertainment were the rush-hour favourites, drawing floods of calls and texts. Villagers, traders, and drivers, she says, still tune in regularly, especially where real-time traffic updates can shave hours off a commute. For Hyeladzira, radio’s edge is intimacy, “a local, close-to-home, real-life feel” that algorithms can’t quite replicate. Even in an era of endless audio choices, she believes it’s adapting, slowly but surely, to new ways of listening.

Rabin, an on-air personality for over a decade, recalls the human connection radio created. During a fuel scarcity period, a casual on-air mention of his struggle led a listener to track him down and deliver free fuel. “That day, I realised radio wasn’t just about broadcasting. It was about real human connection.”

He’s clear on what’s changed: the drop in younger listeners began in the late 2010s and sped up during the COVID-19 lockdown, when streaming platforms, podcasts, and social media reshaped listening habits. Still, he believes radio has adapted better than people think, with stations livestreaming shows, creating podcasts, and using social media to meet audiences where they are. And when it comes to Lagos traffic, he believes radio’s real-time updates still make it a companion worth keeping.

Prosper, anchoring indigenous talk shows, music programs, and newscasts, describes radio as a major influencer, recalling moments when traffic updates and weather warnings directly helped listeners. “One listener called to thank us after we advised people to wear extra clothing during nonstop rainfall,” he said. “He told us it saved him from catching a cold.” For him, the biggest shift is in loyalty. “Listeners now follow specific programs or presenters, not whole stations,” he explained. Many never call in, so their numbers are hard to measure.

Prosper also points to how radio has adapted. Online streaming through platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok has become essential. “Any station without a strong online presence is regarded as a joke among its peers,” he added.

From FM to Streaming

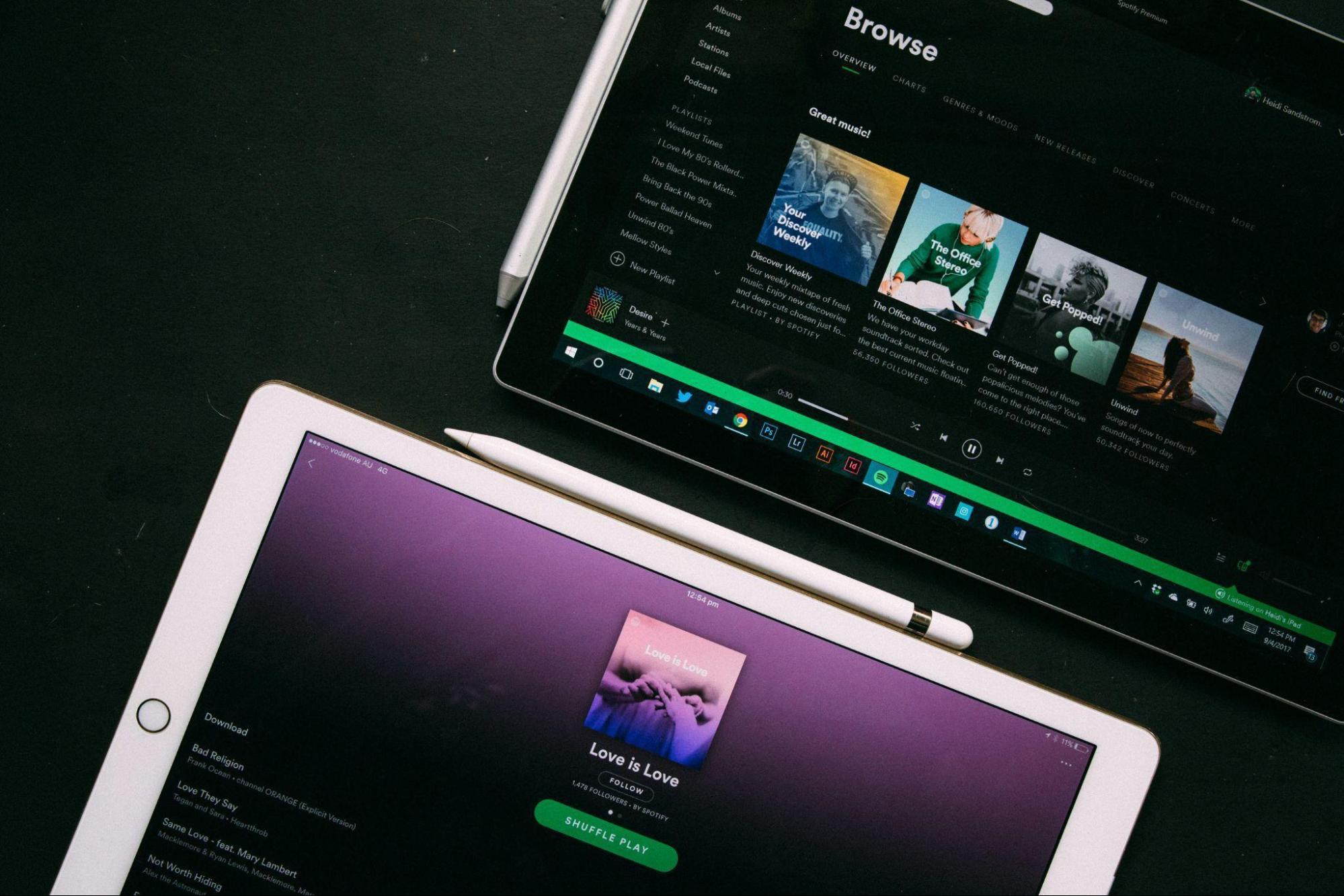

Podcasts and Streaming platforms—Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube Music—have taken the intimacy of radio and made it on-demand, putting entire libraries at our fingertips. Traffic in Lagos is still as bad as ever, but the companion has changed. Now it’s Afrobeats one hour, a business podcast the next, with the occasional “random mix” the algorithm thinks you’ll like.

Even devices have shifted. Many flagship smartphones no longer include FM receivers, so the casual ‘tap the Radio app’ moment is gone for a lot of users. iPhones have never had a usable FM receiver. Google Pixel phones don’t offer FM listening either, and Samsung’s S24 line has no offline FM support, so to listen to a radio, you need to stream through data or an app.

Where FM does still live is on many affordable Androids, especially in brands popular in Nigeria—Tecno, Infinix, iTel, etc.—that list FM radio as a feature, often needing wired earphones as antennas.

So the mobility-radio bond hasn’t broken; it has evolved. Younger commuters with iPhones, Google Pixels, or new Samsungs lean into Bluetooth and streaming. Older drivers and traders still keep small FM sets or use budget phones with built-in tuners. And in Lagos, a station exists to sit in the passenger seat with you, telling you which road to avoid next. You might not twist a dial anymore, but the idea is the same: something to keep you company between Point A and Point B.

Listeners Then and Now

For many Nigerians, radio is no longer the daily companion it once was, but it’s far from gone. Gemini, a Gen Z Lagosian who grew up with 5 a.m. jingles from Radio Lagos, says the internet has largely replaced that role. “Any information you’d hope to catch on the radio, you’ll find it on a blog or trend table. Browsing on my phone is easier than listening to the radio all day.” Yet nostalgia remains: childhood mornings soundtracked by jingles, radio drama episodes that held him in place, and Helen Paul’s Tatafo character on Wetin Dey.

Still, there are moments when radio sneaks back in when he is on the move. On a bus trip to Ile Ife earlier this year, he found himself tuned into a show playing from the driver’s stereo, a reminder that while the form is fading for some, it’s still present on the road.

Francis, a marketing and communications specialist, still tunes in daily, but only while driving. For him, radio has always been tied to routine, first as a child listening to his father’s bedside set, now as an adult catching music shows and football commentary on the way to work. “Radio is where I hear new music and current trends,” he says, noting that ten years ago it was mostly about news. His loyalty is steady but selective: The Beat 99.9 provides just enough rhythm and chatter to make his commute feel alive.

Bolanle, a millennial listener who trusts radio for real-time news and analysis, describes it as a steady presence in her day. “It’s where I get authentic news,” she says, in contrast to the noise of social media. At 5 a.m., the sound of Yoruba news analysis from her mother’s radio is still the memory that anchors her sense of home.

Her listening follows the rhythm of her day. By 7:30 a.m., she’s tuned in to 98.1 FM for news analysis, then later switches to legal talk shows. And when traffic grinds to a halt, she leans on 96.1 FM, Lagos Traffic Radio, for answers maps can’t give. “I always drive with a map, but when I’m stuck, I switch to the radio to tell me why.”

Beyond information, radio for her is presence. It connects her to the “now,” not a playlist on shuffle, not a podcast recorded months ago, but real-time voices, live analysis, and even sermons broadcast on Fridays. She insists it’s far from obsolete: public buses play it by default, private car owners still tune in, and older listeners—like her mother—can’t start their day without it. To Bolanle, radio hasn’t disappeared. It has simply stayed steady while everything else has shifted.

Radio Across Nigeria and Beyond

Outside Lagos, radio’s hold is even stronger. In northern Nigeria, Hausa-language stations remain central for traders, farmers, and drivers, many of whom still rely on affordable phones with built-in FM tuners. In rural communities across the East and South, radio is often the first source of breaking news and weather updates. While streaming dominates in cities, FM sets remain the companion of choice on long-distance roads, at market stalls, and in households where data is expensive.

That closeness to daily life isn’t abstract to me. I saw it firsthand growing up. On nights when there was no light to watch a football match live, my dad would tune in on his small phone with an FM radio. We would sit with him, hearing the commentary pour out of the tiny speaker—the cheers, the fast-paced voices, and the tension in every goal call—and that was how my first love for football began, not by watching the screen, but by watching him listening.

That memory stays with me whenever I think about how radio continues to shape habits across the continent. My younger brother now lives in South Africa, and when we talk about his commute in Johannesburg, he says he often catches a song or two from taxi radios that take him back to Nigeria, whether it’s a familiar Afrobeats track or a station voice that reminds him of nights listening to our father’s radio. Even for someone who mostly streams music, these moments show how radio’s presence lingers across borders.

Compared to Nigeria, countries like South Africa and Kenya show similar divides. In Johannesburg and Nairobi, younger commuters lean on Spotify, YouTube, and podcasts, while minibus drivers and township communities keep FM alive. Kenyan stations like Classic 105 still pull mass audiences during rush hour, much like Wazobia or Cool FM do in Nigeria. The difference is pace: in South Africa and Kenya, digital adoption has moved faster, but across all three countries, radio remains a constant on the road, its voice woven into the rhythm of daily life even as listening habits evolve.

The Sound of the Road, Then and Now

Radio has always moved with the city’s pulse. It rides with you through early-morning fog and late-night traffic, threading its way into the pauses between stops and starts, into the rhythm of the streets. It hums in danfo buses, whispers from car dashboards, and fills quiet corners where the day begins or ends.

It’s more than music or news; it’s a presence, a way of marking time, signalling the start of the day, or offering a familiar voice during long commutes. Morning hosts, traffic updates, and call-in shows transform silence into company, and even the smallest station announcement can feel like a companion, even as horns blare and engines idle.

Fewer people may listen now, but for those who do, radio still matters. It connects them to routines, to information, and sometimes to each other. In a world crowded with playlists and podcasts, it continues to guide journeys, share moments, and hold its quiet, persistent place on the road.