These days, the real Game of Thrones isn’t about kingdoms or dragons—it’s about finding a decent parking space in Lagos. A typical day driving in the city begins with calling your neighbour to reverse their car so you can manoeuvre yours out. Then you hit the road, spending 30 minutes in traffic, followed by another 10 minutes hunting for a parking spot. As you head home, the struggle continues—another 20 minutes searching for the person who blocked your car, followed by an hour trapped in traffic before finally arriving at your destination. You collapse into your bed, questioning your life choices and contemplating a move out of the city—plans that, of course, never materialise. And then the cycle repeats.

As some residents break free from the rickety yellow buses, others expand their car collections. However, this increasing number of vehicles has heightened the demand for parking spaces, and the infrastructure has failed to match the pace. In typical Nigerian fashion, residents have devised creative solutions to government oversight, resorting to using road sides as parking areas, which creates a whole new problem of cars overcrowded streets.

In Nigeria, it’s not uncommon for a tenant to own three cars while the landlord has just one, reflecting the deep cultural significance attached to vehicle ownership. Cars are not merely modes of transportation; they are status symbols, with many aspiring to possess multiple vehicles as markers of success. This mindset contributes to the high density of cars in urban areas, where parking space is already at a premium. Additionally, there is often a reluctance to embrace alternative modes of transportation, such as biking or public transit, as the convenience of private vehicles remains a strong preference.

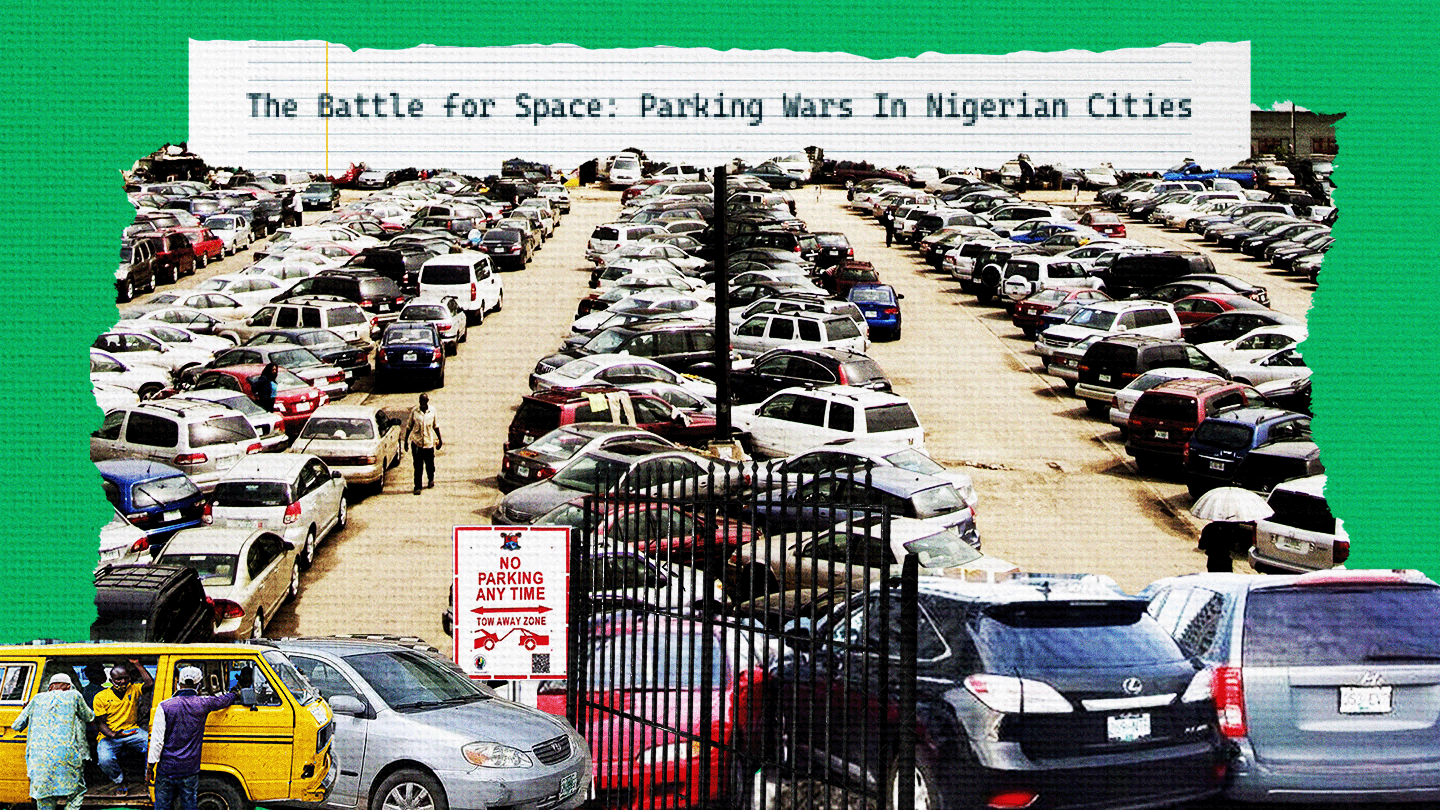

The parking crisis in Nigerian cities, particularly Lagos, stems from significant shortcomings in urban planning. It is not uncommon for residential buildings housing dozens of people to provide parking for only a handful of vehicles. The root of the issue lies in the failure to anticipate rapid population growth and the corresponding surge in vehicle ownership. Narrow roads and poorly conceived public spaces have created a perfect storm of parking scarcity. Existing parking spots are often inadequate, forcing cars to spill onto sidewalks and block entrances, effectively turning neighborhoods into makeshift parking lots.

With the constant knowledge that a parking spot may be elusive, drivers are increasingly willing to ignore “No Parking” signs and park wherever they can find space. This issue is exacerbated by informal parking attendants, commonly referred to as “area boys,” who capitalise on the parking shortage. They assert control over street parking spaces, demanding fees from drivers before they can leave their vehicles, often accompanied by threats of towing if their demands are not met.

In response to the growing scarcity, private parking operators and local authorities have raised parking fees, turning what should be a minor expense into a significant financial burden for many drivers. In areas like Alaba Market and Computer Village, parking costs range from ₦500 to ₦1,000, while at airports, fees vary based on duration. Typically, short-term parking averages around ₦500 to ₦700 for the first hour, with each additional hour costing ₦200 to ₦300. Long-term parking at major Nigerian airports can range from ₦3,000 to ₦5,000 per day.

In June 2023, the Lagos State Government established the Lagos State Parking Authority (LASPA) in response to the escalating parking crisis. This agency is tasked with addressing the city’s parking challenges and fostering a more sustainable urban environment. LASPA’s primary mandate includes monitoring both private and commercial parking facilities to prevent indiscriminate parking along roads—a long-standing issue in Lagos.

The authority has implemented a system of parking levies, ranging from ₦150,000 to ₦23 million annually, depending on the size and nature of the business premises. This initiative aims to regulate parking and generate revenue for urban development. LASPA also enforces regulations through measures such as clamping vehicles parked in restricted areas and issuing demand notices to ensure compliance.

To promote a well-organised parking culture, LASPA has launched public awareness campaigns to combat misinformation and highlight the benefits of its regulatory framework. Warning signs have been posted on properties, and efforts are being made to improve communication with vehicle owners, emphasising the importance of adherence to parking regulations for a more efficient urban mobility system.

The parking crisis in Lagos reflects deeper systemic issues in urban planning, cultural attitudes toward vehicle ownership, and the challenges of rapid urbanisation. While the establishment of LASPA shows that the government is taking steps to address the issue, it will require a concerted effort from both authorities and residents to create a sustainable and organised urban environment.

The battle for parking in Lagos is far from over, but with the right policies, enforcement, and a shift in mindset, there is hope for a more navigable future in this ever-growing city. In the end, it might just be cheaper and less stressful to Uber your way through the city.