Just like 2go, Mary Kay and BlackBerry, the Peugeot car brand once had Nigerians in a choke hold. Today, the word on the street is ‘Benz or nothing’, but back in the day, the big boys in Nigeria drove Peugeots.

Founded in 1810, Peugeot, a French automobile brand, is one of the oldest car companies in the world. Like many old car companies, Peugeot started off by making bicycles. They then moved to steam-powered cars, before finally manufacturing internal combustion engine- (ICE) powered vehicles. Another notable part of the company’s evolution is its logo, which has morphed from one form of a lion to another, the latest update (as of 2021) being a sleek, stylised roaring lion’s head inside a shield. The lion continues to symbolise the company’s durability, power and elegance.

Peugeot’s Reign in Nigeria

Peugeot’s popularity in Nigeria is in part credited to the establishment of Peugeot Automobile of Nigeria (PAN). On 11 August 1972, a joint venture agreement was made between the Federal Government of Nigeria and Automobiles Peugeot of France. The agreement would see the establishment of a car assembly plant in Nigeria for the production and marketing of Peugeot passenger cars. The company was to be located on a site of approximately 200,000 square meters at Kakuri Industrial Estate, Kaduna.

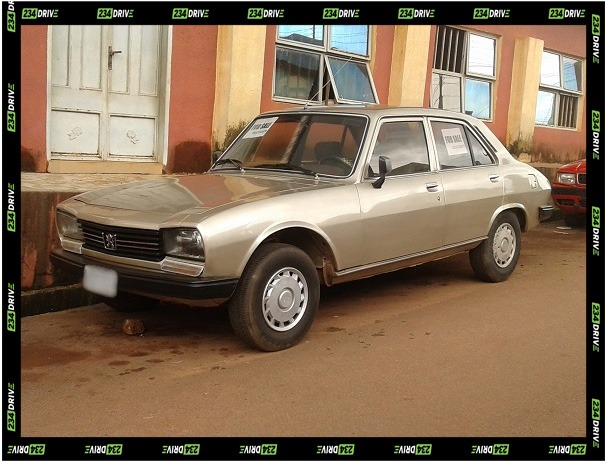

Three years later, on 14 March 1975, vehicle production began in earnest with inputs shipped in bits and pieces from abroad. Within the first 10 years, 342,262 cars were rolled out of the Kaduna plant. The company kicked off with the 504 model and later introduced the 505 in 1980. Between 1975-85, the 504 became very popular amongst Nigerians—especially the middle class—who perceived it as a reliable, affordable car and thus nicknamed it the ‘Nigerian Car’.

The Peugeot 504 was so prominent that it became the official car of General Olusegun Obasanjo, Nigeria’s Head of State in 1979. With things at an all-time high at PAN, one would have thought that things could only get better. However, much like it is in movies, a tipping point was inevitable. By 1987, Nigeria’s economy experienced a downturn that took its toll on the company’s operations. This marked the beginning of Peugeot’s decline in the country.

Peugeot’s Eventual Decline in Nigeria

1986 saw a rise in the dollar rate, with one dollar becoming 2.02 naira, from 0.894 naira the previous year. By 1987, the dollar rate had doubled once again, becoming 4.02 naira to a dollar. This meant that the cost of production of a single Peugeot car had quadrupled in barely two years. This economic descent was the aftermath of the infamous 1986 Oil Price Collapse.

An increase in production cost meant that the assembled in Nigeria Peugeots became expensive overnight. One of the appeals of the Peugeot at that time was its price point, but as soon as the price went up, the middle class Nigerians who had been the major Peugeot buyers went in search of cheaper imported alternatives—most of which were from Japanese car companies. A review of the Manufacturers Suggested Retail Prices (MSRPs) of some vehicles compared to Peugeots in 1987 brings things into perspective. An MSRP is basically the price at which a manufacturer of a product recommends that a retailer sell the product.

Peugeot’s Competition in the 1980s

The Peugeot 505 as of 1987 had an MSRP of 13,900 USD, equivalent to 56, 156 NGN. Bearing in mind that the exchange rate was a dollar to 4.04 naira in 1987. On the other hand were the Japanese alternatives, including the Nissan Sentra priced at 7, 899 USD (31, 911 NGN), Honda Civic priced at 8, 455 USD (34, 158 NGN) and Toyota Corolla priced at 8, 178 USD (33, 039 NGN). On the German side of the globe was yet another alternative: the Volkswagen Jetta priced at 9, 510 USD (38, 420 naira).

The rise in the dollar exchange rate shot up the cost of producing Peugeot vehicles. This meant that it became just as expensive to produce them locally as to import them. The initial goal of PAN was to eliminate the problem of sending huge sums of money abroad for the importation of cars into Nigeria, but with the economic downturn of 1987, PAN could no longer meet this objective. The middle class Nigerians eventually fell in love with the cheaper alternatives like Nissan (Datsun), Honda, Corolla and Volkswagen.

Peugeot Finding Back Their Feet in Nigeria

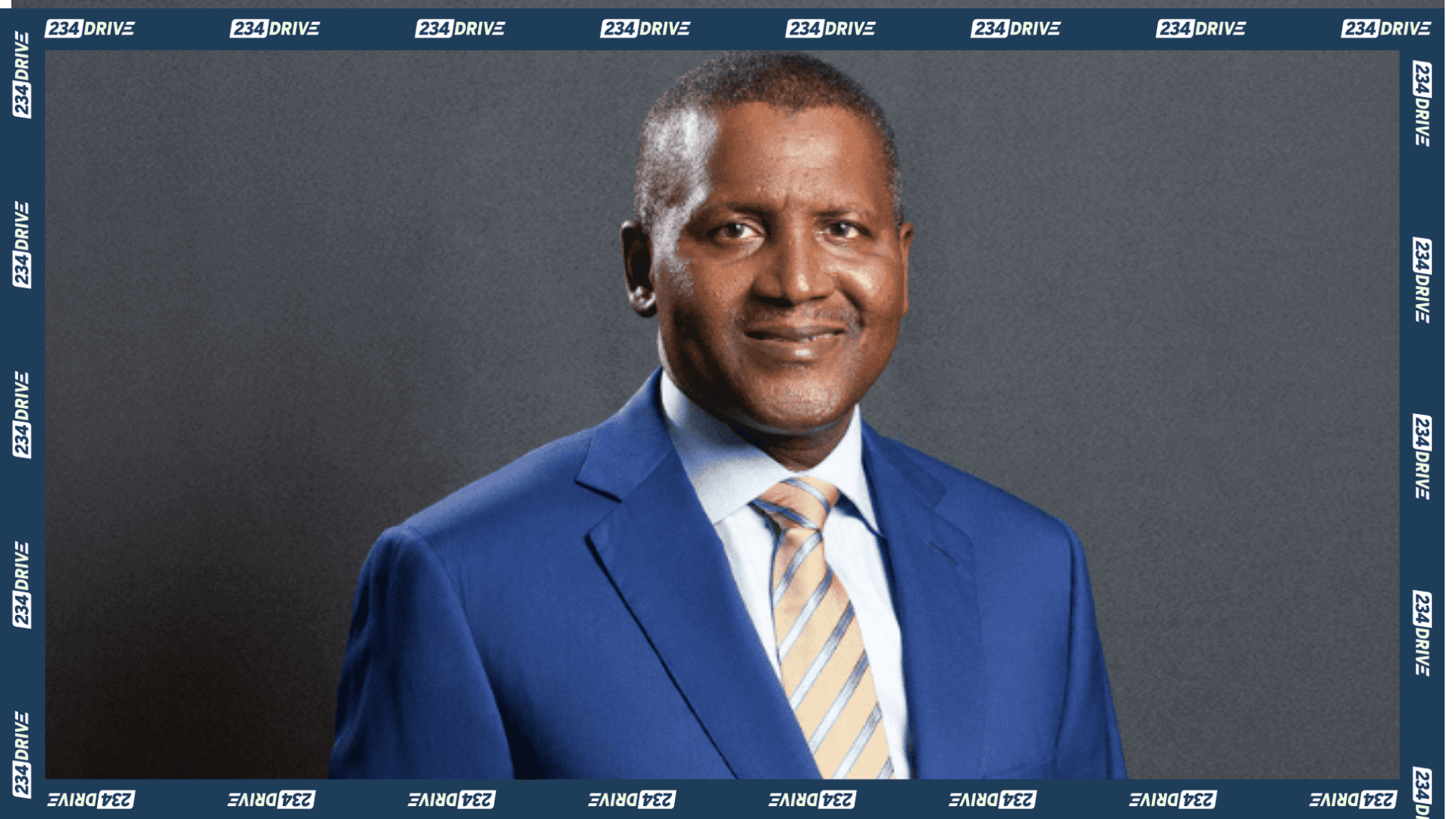

Peugeot’s supposed comeback story began nine years ago in 2016 when Aliko Dangote, Africa’s richest man, bid for a majority stake in Peugeot Automobile Nigeria (PAN). However, he did not do this alone. The business tycoon teamed up with two Nigerian states, Kaduna and Kebbi, along with the Bank of Industry (BoI) for this acquisition. The former Governor of Kaduna, Nasir El-Rufai revealed at the time, ‘We have submitted bids for the carmaker with Aliko Dangote on board together with BoI, Kebbi and Kaduna State, we are confident our bid will sail through’.

One may ask, what could have made Dangote interested in acquiring Peugeot? Well, the previous year, specifically in November, an important meeting took place. Peugeot’s then Executive Vice President for Africa and the Middle-East, Jean-Christophe Quemard, met with the former President of Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari to discuss reviving local production. Buhari’s presidency was very keen on promoting a ‘Made in Nigeria’ industrial policy. Dangote’s track record over the years tied in perfectly with this policy, so perhaps this is why he chose to invest in PAN. Another question may be, who is Aliko Dangote?

The Business Magnate behind Peugeot’s Comeback

Aliko Dangote, as mentioned earlier, is the richest man in Africa. He is the founder and president/chief executive of the Dangote Group which currently has a presence in 17 African countries. The Dangote Group is the market leader for cement on the continent. Aside from cement, the group has diversified into other business sectors including agriculture and fertilizer complexes in Africa. As of late, the Dangote Group has constructed a petroleum refinery in Nigeria and intends to supply Nigerians with Premium Motor Spirit (PMS). Evidently, Dangote is pro-locally made products and thus, his investment in PAN is a no-brainer.

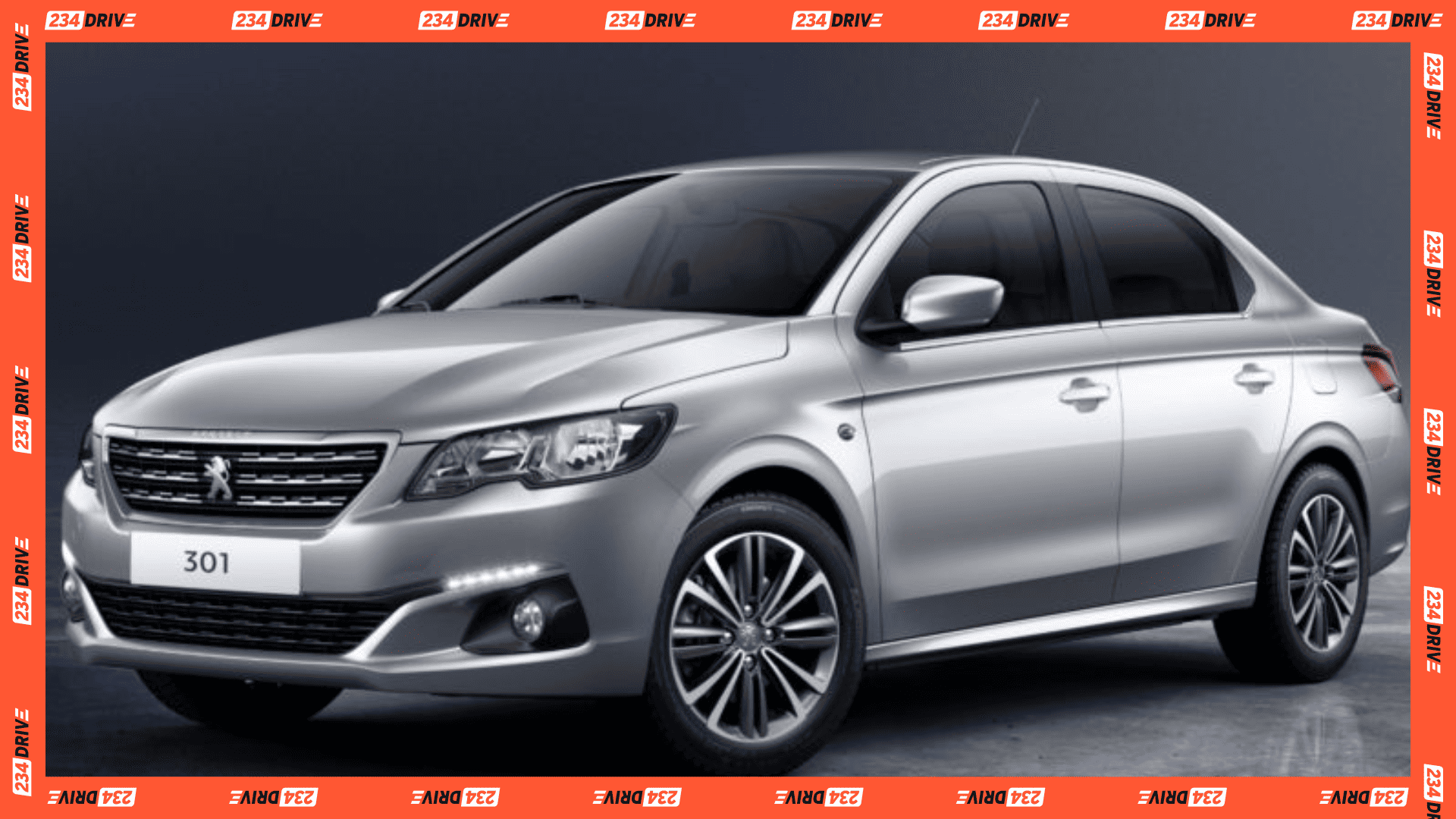

Dangote Peugeot Automobile of Nigeria (DPAN) was formed after Aliko Dangote obtained majority shares in PAN. This is customary as a business usually assumes the name of the key member of a syndicate. After roughly a year, Dangote secured a license for a Peugeot assembly plant which now operates from the Greenfield Ultima Assembly Plant in Kaduna. The Peugeot 301 sedan is already being assembled at the plant with a daily capacity of 120 vehicles per day across two shifts. DPAN has recently expanded their production line to include the Peugeot 3008 GT SUV. Additionally, DPAN has plans to expand their lineup to include the Landtrek pickup, 5008, and the 508 models in the near future.

A Déjà Vu Moment

With the current trend at DPAN, it seems like a comeback of Peugeot in Nigeria is on the verge. But this is not the first time private investors had indirectly led to PAN’s failure. Aside from the economic downturn which increased the cost of production, the federal government of Nigeria had sold its stake in Peugeot to local core investors in 2006. In order to make a profit, cheap second-hand vehicles were imported from Asia. More so, poor manufacturing infrastructure further reduced quality of vehicles and sales dropped, further hurting profits. Operations at PAN nosedived and accrued debt.

The Asset Management Company of Nigeria (AMCON) initially came to the rescue by buying off PAN’s debt and converting a portion to equity. By doing so, they obtained 79.3% of PAN Limited. Unfortunately, the banking crisis of 2009 adversely affected AMCON. This was when they decided to sell off their shares in PAN, the very same shares Dangote eventually obtained.

What if History Were to Repeat Itself?

Dangote’s track record so far strongly counters the probability of DPAN running into debt like it did in the past with other private investors. Dangote Group has successfully been in business since 1977—nearly five decades! Many businesses come and go, but Dangote Group has stood the test of time. So, it’s safe to say the chances of DPAN’s survival are quite high.

All things being equal, the Nigerian-assembled Peugeots should be slightly cheaper than their imported counterparts. This would ultimately promote local car consumption, thereby reducing the dependence on imports and strengthening the economy of the country. Fingers are crossed as only time will tell how the story of DPAN will turn out. What are your thoughts on Peugeot’s supposed comeback? Do you think they have a chance against the likes of Toyota and Mercedes Benz in Nigeria?