For decades, the Nigerian automotive market has been defined by the tokunbo—used vehicles shipped primarily from US auctions—but a seismic currency shock is now forcing a radical, irreversible pivot toward Asia. This sharp devaluation of the naira, which has seen the cost of traditional imports surge by as much as thirty per cent since 2022, has fundamentally shifted the buying power of the Nigerian middle class. Instead of accepting ten-year-old, basic-spec vehicles, buyers are turning decisively toward newer Chinese models, including new offerings from brands like Chery, Jetour, and MG, alongside cleaner used imports (2019 onwards) sourced directly from Chinese wholesalers. This movement is dramatically transforming Africa’s largest used-car market, with demand for used cars still strong, yet buyers are now securing modern vehicles with warranties and infotainment systems for the same budget, typically ranging from ₦16–20 million.

The primary appeal of the Chinese cohort is the technological value proposition it unlocks. For a budget previously stretched to purchase a decade-old model like a Toyota Corolla, vehicles such as the Chery Tiggo 7 Pro and Jetour X70 Plus now offer access to features like adaptive cruise control, 360-degree camera systems, panoramic sunroofs, and hybrid powertrains. These newer cars arrive backed by five-year warranties and burgeoning service networks, directly addressing modern consumer desires for connectivity and fuel efficiency amidst soaring petrol prices. This focus on advanced technology and inclusive features is specifically engineered to target the middle-class segment, making recent-model ownership a realistic goal again for civil servants and tech workers previously excluded from the new-car market.

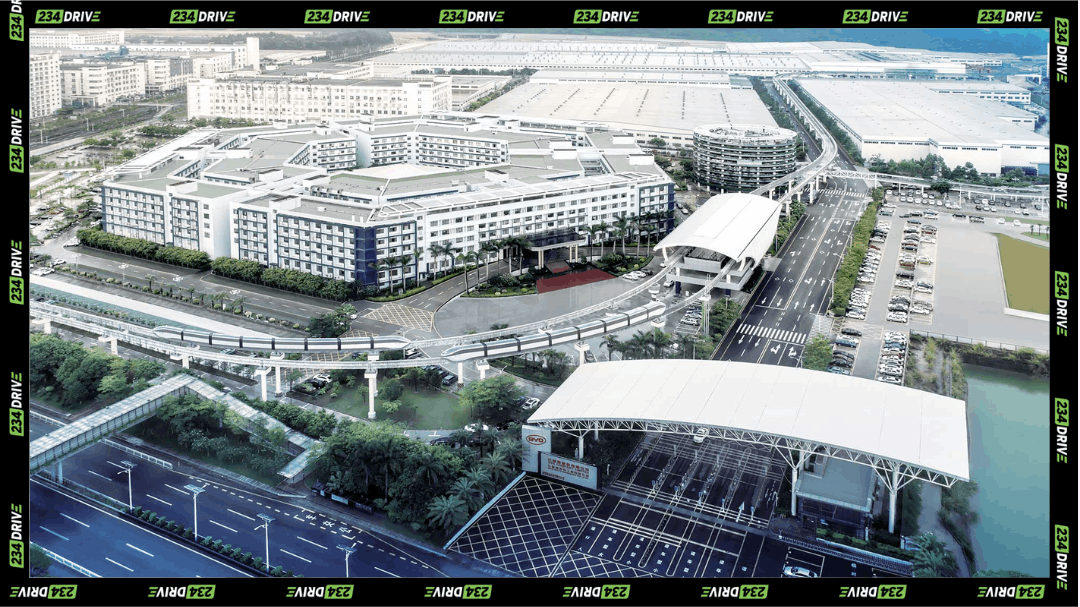

The new market dynamic is driven by several key players who recognise the economic necessity of change. On the consumer side, squeezed urban professionals and ride-hailing fleet operators are prioritising lower running costs and modern features over legacy prestige. For the supply chain, local dealers and importers, notably TIM Motors, are aggressively partnering with Chinese manufacturers, aiming to convert ten to twenty per cent of the traditionally tokunbo-dependent buyers to new cars within three years. This ambitious strategy is backed by local financing partnerships offering 24–48 month loan terms and is cemented by plans for local assembly plants, such as the one projected for Abeokuta by 2026, which promises job creation and better parts availability.This pivot signals that Chinese cars now dominate the new vehicle segment in Nigeria.

Fundamentally, this trend signals a significant strategic shift for the entire national automotive ecosystem: a necessary move from prioritising brand pedigree and legacy resale value to embracing pragmatism and sheer affordability. The naira’s collapse—a devaluation exceeding seventy per cent since mid-2023—has made importing traditional tokunbo vehicles from North American auctions economically untenable, especially when compounded by import duties and levies that can add up to fifty per cent of the vehicle’s original value. This economic pressure has led to a dramatic drop in the volume of used vehicle arrivals, with the value of tokunbo imports plummeting by 81.5 per cent in the year leading up to Q2 2024. This structural weakness in the old supply chain is forcing the market to seek structurally cheaper sourcing alternatives from the East. The local market, meanwhile, sees locally-used cars boom as volatile naira curbs imports.

The competitive edge of the Chinese supply chain lies in its direct sourcing capabilities. By procuring vehicles from wholesalers and auctions in manufacturing hubs like Guangzhou and Shanghai, dealers can bypass multiple middlemen and avoid some high US tariffs on salvaged stock, undercutting traditional routes by up to ₦3 million per unit. This direct channel also speeds up logistics, reducing shipping times to Lagos ports to a rapid 28–35 days, providing the market with a quicker, cheaper influx of stock. This advantage highlights why buying directly from China saves you more on used cars. This operational efficiency is directly translating into market share gains, with brands like MG surging by 60.6 per cent in new vehicle registrations in the first half of 2025, firmly claiming the fourth spot overall and demonstrating rapid consumer acceptance of this global re-alignment.

However, the rush toward affordability is not without significant caveats, particularly concerning long-term value and integrity. While the promise of direct imports suggests lower prices, the final price of brand-new models is often significantly inflated by Nigeria’s structural economic risks. Established dealerships, whose pricing is sometimes publicly scrutinised, must build margins to absorb massive costs: customs duties (which can total 30–45% of CIF value), extreme FX volatility, and high-interest capital (25–30% per annum) required for inventory. This ‘markup’ is crucial, as it pays for the essential after-sales infrastructure, long-term warranties, and service networks that are entirely absent when buyers attempt to import cars individually.

Furthermore, the long-term resale figures for Chinese models typically lag, retaining only fifty to sixty per cent of their value after three years, compared to the seventy to eighty per cent retention famously commanded by Japanese brands like Toyota. Moreso, spare parts availability for some Chinese models remains spotty outside the main urban hubs, leading to frustrating downtime. More critically, the appeal of direct imports from China invites heightened fraud risks. Buyers must exercise extreme caution, facing dangers such as odometer tampering, undisclosed flood damage, or salvage titles, demanding stringent due diligence, the use of escrow services, and verified history reports to reduce risks when importing used cars.

The current wave of adoption is built on a track record of aggressive growth, with Chinese passenger car exports to Africa doubling year-on-year in the first half of 2025 alone. This momentum is supported by domestic government policies, including bans on importing vehicles over twelve to fifteen years old, which naturally favour the newer stock arriving from the East. Ultimately, the overall market may have contracted by 18.4 per cent due to the foreign exchange scarcity, but the Chinese segment is the rare pocket of expansion, proving their value proposition is gaining undeniable credibility across commercial and private sectors. This growth demonstrates that Chinese brands overtake others in Nigeria’s new car market.

This historic pivot is successfully easing middle-class access to modern mobility options through dedicated financing schemes. Yet, the wider economic implications are complex: while newer fleets may slightly reduce emissions and create assembly jobs, the continued high volume of all imports still exerts intense pressure on Nigeria’s scarce foreign exchange reserves, potentially slowing the overarching goal of achieving genuine local manufacturing self-sufficiency. As the choice shifts from legacy reliability to modern value, the market is left to ponder whether the newfound affordability of Chinese vehicles is a sustainable fix for the mobility crisis, or simply a necessary gamble reflecting an economy where, for most buyers, spending heavily on the perfection of a bygone era has become the true tokunbo myth.