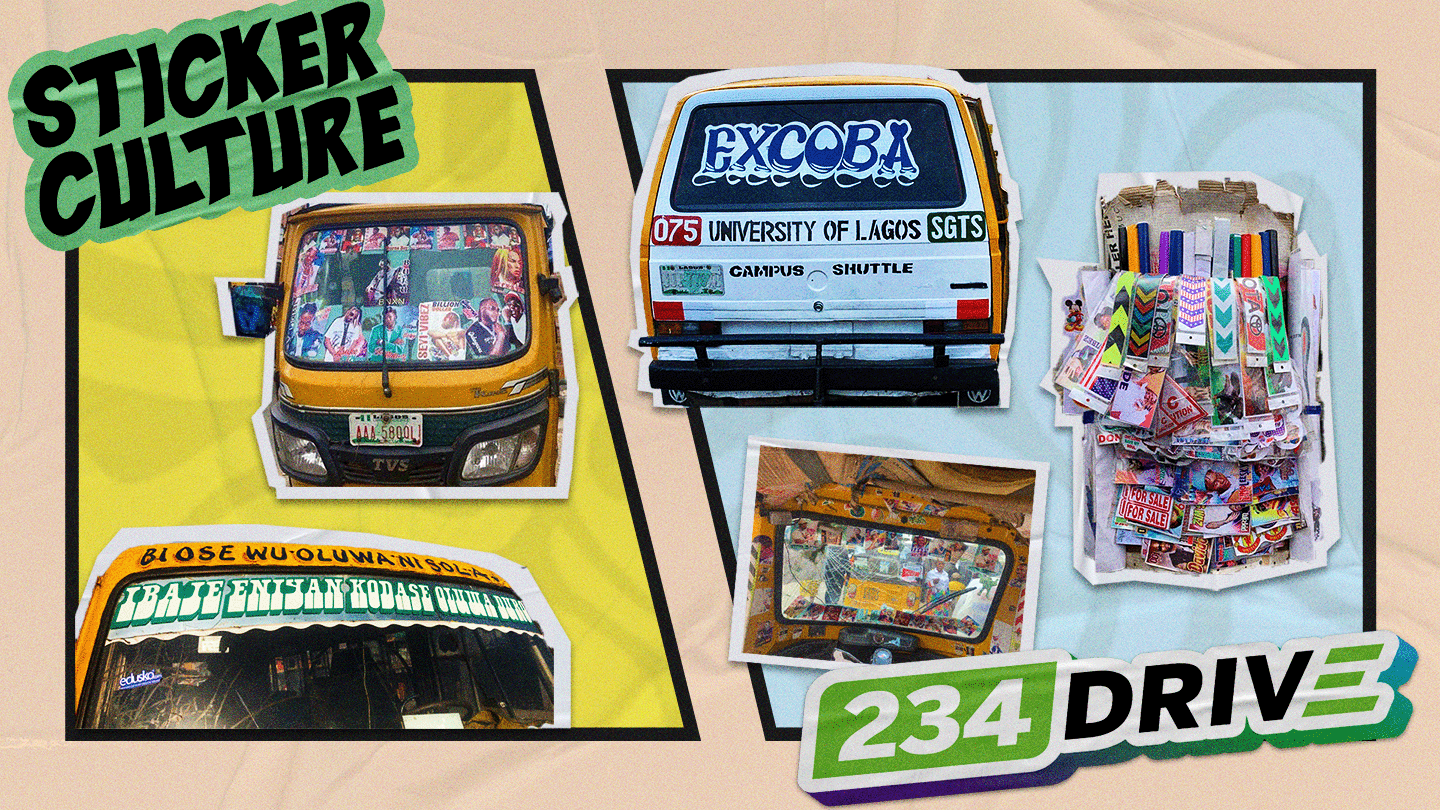

Here, art meets mobility. Public transport vehicles are moving canvases which are transformed into vibrant displays of colorful vinyl inscriptions and images. These vehicles are more than just modes of transport; they are visual storytellers, offering a window into the drivers’ worldviews, beliefs, and personalities through messages written in Yoruba, Igbo, Arabic, Pidgin English, and more.

A closer look reveals deeply spiritual and motivational themes. Prayers, quotes, and theistic expressions like “Obaanu” (God of mercy), “So pe ti e” (Thank God for your own), “GOD DEY” (God is present), ‘Yah lateef” are common. These phrases reflect not only the spiritual nature of Nigerian society but also the resilience of its people, who hold fast to the power of words to navigate the challenges of daily life.

The vehicles also serve as rolling billboards for Nigeria’s vibrant music scene, with stickers featuring popular artists like Pasuma Wonder, Wizkid, Burnaboy, Olamide, Portable, and more recently, Asake. In fact, for a musician, having your image plastered on the windscreen and body of cars across the country is a significant indicator of public acceptance and popularity—a visual metric of success in the country’s competitive music industry.

In the public transport scene, a vehicle without stickers feels out of place. New vehicles entering the fleet soon adopt stickers, much like how most musicians start their careers without tattoos but end up covered in ink within a year. What may start as a simple attempt to blend in often evolves into a meaningful form of self-expression, allowing drivers to share their beliefs without uttering a word.

Private vehicles, though often more restrained in their use of stickers, also embrace this culture. Here, stickers carry deeper personal significance, reflecting religious affiliations, professions, or humor for fellow drivers to enjoy. Some stickers display faith-based declarations, like the MFM logo for Mountain of Fire Ministries, “I AM WINNER” for Winners Chapel members, “I AM CHOSEN” for Chosen Church followers, or “I’m a proud Muslim,” with some drivers believing these stickers offer protection from accidents.

Others use stickers to highlight their profession, such as “Sue that bastard” signaling that the owner is a lawyer. On some cars, you’ll find humorous decals like “My Benz is at home,” pasted on a Toyota Corolla, offering a lighthearted moment on the road.

How it started…

The roots of this sticker culture stretch back to the 1970s. Before vinyl stickers became mainstream, Nigerian drivers already had a history of personalizing their vehicles. It started with custom paint jobs and bold slogans identifying transport companies. As Nigerians began white-collar jobs, their purchasing power increased, and owning a vehicle became more common. Vehicle owners outfitted their vehicles with stickers for aesthetic purposes and to signal class mobility.

Bolekaja, Teni Begi Logu Transport service

Stickers became a medium for class placement, varying with the type of vehicles. Old cars bore stickers that read: ‘the downfall of a man is not the end of his life’, or ‘my beginning may be small but my latter end shall be great’. Cars that were fairly new would have stickers like ‘a patient dog eats the fattest bone’, ‘what the Lord has started in me, he will perfect’, etc. Classier and flashier cars would have stickers that said: ‘the storm is over’, ‘one with God is majority’, ‘back to sender’, etc. This did not just explain class consciousness but also the individual psychological self- awareness.

As the gap for public transportation persisted, individuals began using their vehicles for popular commercial routes, kickstarting the use of inscriptions for identification purposes as the private commercial vehicles at the time bore basic descriptive inscriptions such as ‘goods only’, ‘private’ or ‘goods or owner’s risk.

Some of the earliest public transport vehicles with inscriptions were the Bolekajas, roughly translating to “come down and let’s fight.” These vehicles, alongside others like the Molue, introduced the practice of self-expressive inscriptions, mixing motivational quotes, personal experiences, and commentary on social or political matters. While many of these phrases were written in English, local languages and pidgin English remained prominent, with sayings like “Fálànà gbó̩̩ tìe̩” (Mind your own business), “Igi á rúwé” (The tree will sprout leaves), and “Nagode Allah” (Thank you God) becoming common from the 60s through the mid-70s.

Hands behind the sticker culture in Nigeria

Stickers are a common sight on Nigerian roads, but many people overlook the craftsmanship and business model behind these eye-catching designs. According to Audu, a sticker artisan we met at Jibowu bus stop, the trade is a specialized skill primarily learned in Katsina, Nigeria. Artisans like him hand-cut stickers into various lettering styles and patterns based on customer preferences, ensuring each design is unique. while both vinyl and paint services are offered, vinyl has become more popular due to its faster application time and higher demand, Audu explained.

The craft, passed down through informal apprenticeships, remains largely undocumented, with techniques conveyed orally from one generation to the next. Once trained, many artisans establish their own shops, often branching out into other forms of printing like business cards or even mobile print shops, bringing the craft directly to customers.

“Dem no dey learn this work for school. Dis work dey take us like six months to learn, we go dey under our oga dey watch am as e dey do am. Den after sometime we go try to dey make our own. When we see say we don sabi cut all the letters wey dey alphabet we go get our freedom. Some people dey travel go other place for better work, like me now I come Lagos,” Audu shared.

As Audu demonstrated his work for us, cutting out a sticker, we saw this skill in action. Using vinyl sheets in blue, yellow, and green, and a pair of scissors, he began by cutting a rectangular shape to create space for the letters. He then used this as a template to cut the remaining letters. For symmetrical letters, we noticed that Audu folded the sheet in half before cutting. After finishing the letters, he carefully pasted them onto a larger green sheet, showcasing the precision and artistry behind a craft many take for granted.

The culture of adorning vehicles with stickers in Nigeria is more than just an artistic trend; it’s a form of self-expression, storytelling, and a reflection of societal values. From spiritual declarations to humorous quips, the stickers that adorn vehicles continue to evolve while maintaining a deep connection to Nigerian identity. As long as roads remain filled with beliefs, personalities, and the vibrant lives of Nigerians, the sticker culture seems far from fading. It stands as an enduring testament to the creative spirit and resilience of the people.