EV World Africa, a Lagos-based sustainable mobility consultancy and advocacy group focused on accelerating electric vehicle adoption across Africa, has been instrumental in demonstrating the viability of EVs through practical testing and public education. When EV World Africa’s 2019 BYD Tang EV600 pulled back into Lagos after a 540 km, two-day round trip to Akure, it wasn’t just another road test, it was a reality check for Nigeria’s electric-mobility dream. The Lagos–Akure–Lagos route, notorious for potholes and erratic power supply, became a test bed for whether an electric SUV could survive real Nigerian driving conditions. It barely flinched but the journey exposed just how far the country still has to go before e-mobility becomes practical for the average driver.

The trip began on Friday, September 26, 2025, in Ibeju-Lekki with a near-full battery (98%) and wrapped up in Akure, Ondo State, after covering about 270 km. The BYD Tang EV600 arrived with 31% battery remaining, having consumed roughly 67% on the outbound leg. The return leg drained 74%, mostly due to higher speeds (up to 120 km/h), full air-conditioning, and mild traffic delays. EV World Africa used the journey to collect live battery-efficiency data — 0.20 kWh/km outbound and 0.23 kWh/km inbound — metrics that match mid-range global averages under conservative driving. An overnight recharge at Bon Hotel Royal Parklane in Akure, using a 7 kW AC charger, restored the SUV to full charge within eight hours. The return trip to Lagos began on Saturday, September 27, 2025, around 9:00 a.m., and concluded later that evening after covering another 270 km, successfully completing the round journey. That single stop demonstrated a workaround many Nigerian EV users may rely on: using hotel or office power sources overnight while travelling between cities.

The Tang EV600 houses an 82.8 kWh battery rated for about 500 km (NEDC), though real-world tests average 400 km on mixed terrain. It’s a seven-seater, all-wheel-drive SUV weighing over 2 tonnes—not the kind of car that shies away from rough asphalt or uneven shoulders. Its weight, however, highlights the stress local roads can impose on EV suspensions, something future adopters must factor in.

The trip’s energy consumption revealed patterns typical of EV performance in tropical conditions. From Lagos to Akure, the SUV covered about 270 km, consuming 67% battery capacity while maintaining speeds under 100 km/h with minimal AC use. On the return, the same distance consumed 74% due to faster speeds, heavier AC, and minor traffic holdups. A shorter trip between Lagos and Ijebu Isiwo, estimated at around 130 km, recorded only 26% battery usage, showing better efficiency for short to mid-range drives. Another test to Ore showed about 50% consumption, complicated by multiple police stops and brief idling. These numbers suggest that with disciplined driving and proper route planning, EVs like the BYD Tang can handle inter-state travel in Nigeria’s current infrastructure reality.

While the numbers prove EVs can technically handle inter-state travel, the experience revealed persistent friction points. Police and customs stops were frequent and often unnecessary, costing an estimated 2% of battery due to idling. Power supply gaps forced reliance on hotel generators and inconsistent grid electricity. Road conditions—especially around Ore and Ondo—were riddled with potholes and occasional flooding, which increased resistance and reduced efficiency. These align with the broader national challenges facing Nigeria’s EV development, including unreliable electricity supply, a shortage of charging infrastructure, and the high cost of imported vehicles and components.

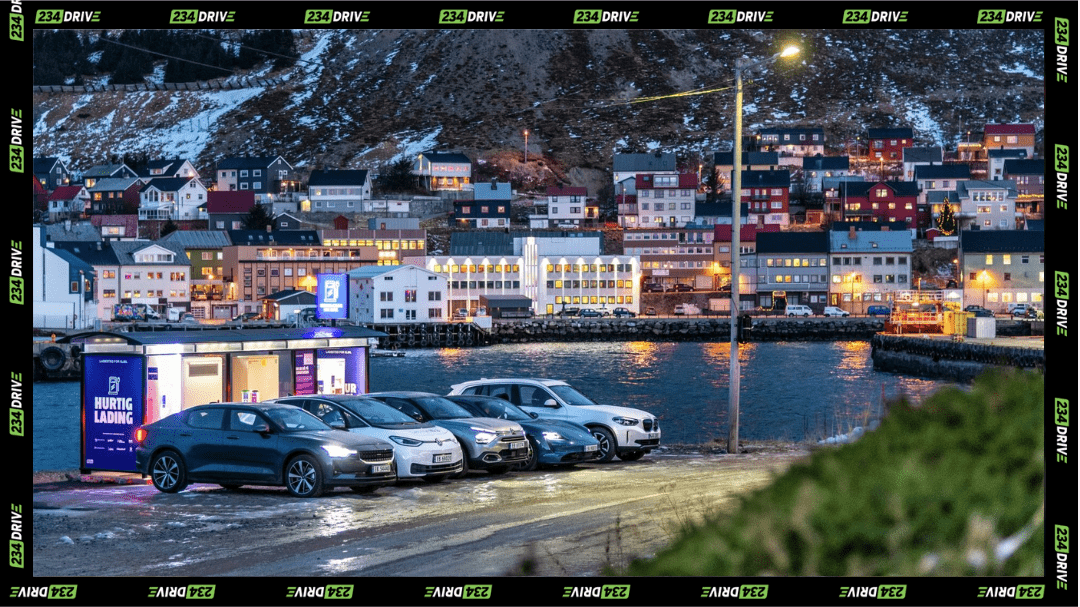

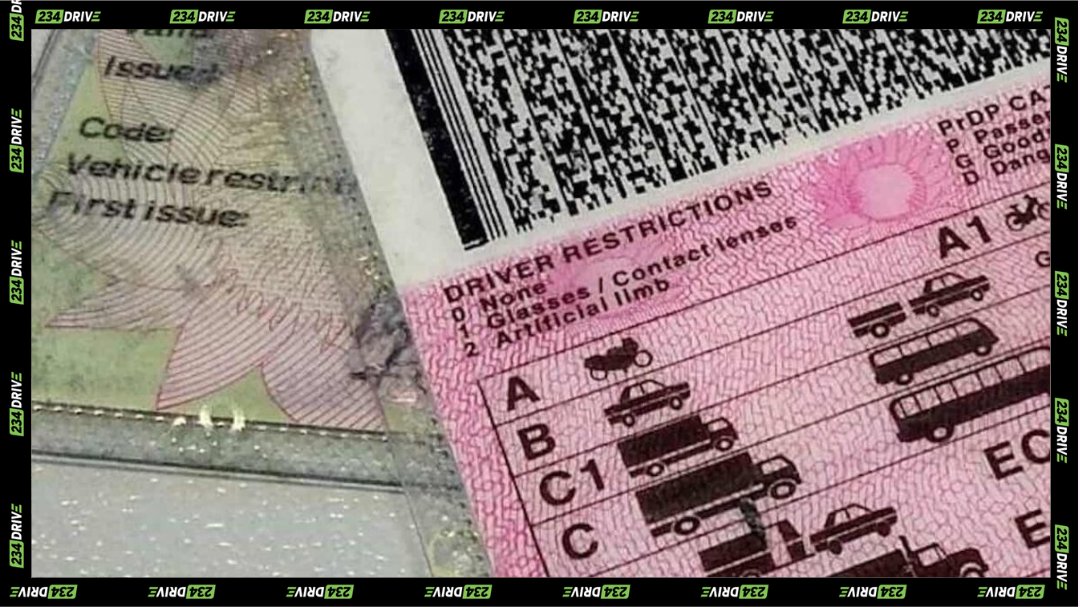

Nigeria’s logistics and fleet sectors are already exploring partial electrification. Start-ups like Max and Kobo360 are testing EV delivery vans in Lagos, but private adoption remains slow. The BYD Tang’s successful run suggests inter-city EV mobility is viable with planning, yet widespread uptake depends on three variables: affordable charging access, preferably DC fast chargers along federal highways; policy incentives such as reduced import duties or dedicated EV lanes; and public education to counter myths about poor performance and battery fires.

Countries like South Africa and Kenya are moving faster. South Africa plans 10,000 public charging points by 2030, while Kenya’s Roam and Basigo already operate electric bus fleets in Nairobi. Nigeria’s grid instability and fuel-subsidy culture make such progress tougher but not impossible.

The Lagos–Akure experiment stands as proof-of-concept. It didn’t just silence skeptics; it reframed expectations. Nigeria’s EV movement won’t accelerate because of hype—it’ll move because data like this proves feasibility under harsh conditions. The next test should be longer, perhaps Lagos to Abuja, supported by mobile DC chargers or battery-swap pilots. Whether policymakers treat EV charging as public infrastructure will determine how soon electric road trips become routine rather than newsworthy.