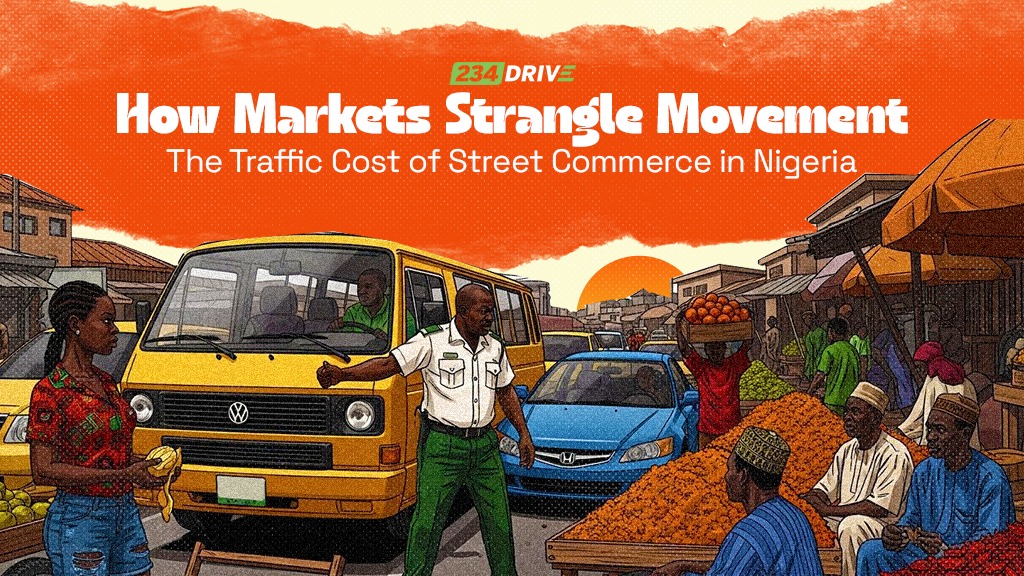

An X (fka Twitter) user, @rahhsznn, once said, “The money you save from using public transport instead of Uber is paid for with your sanity.”

Ask millions of Nigerians, and not a single person could describe this more accurately. Still, that sense of sanity and predictability now feels a little shaky.

You open your Bolt app in Ibadan, setting out from Old Bodija to New Bodija. The fare reads ₦5,300—steep for the not-so-long distance, but you accept it anyway. You hit confirm ride, a driver is found, and before long, the driver calls. His (or her) tone is firm, “Abeg, that price no fit work o. You go need add something.. Like ₦3000, and I go come meet you.”

The first time this happens, you squeeze your brows together wondering, isn’t the fare already calculated by Bolt? What’s my own?

You firmly tell him you will not be paying extra, but before you know it, he cuts the call and you end the trip. The second rider follows the same playbook. You refuse his request but instead offer to add ₦1000, yet that doesn’t cut it for him, so he cancels the ride. You’re on the third rider now, and he asks for almost double the ₦5,300 Bolt has priced your ride. You renegotiate and then end up paying the ₦3,000 extra fee you tried to dodge initially.

Is this situation just the latest symptom of a bigger problem, one where app pricing and economic realities no longer align, or just pure greed?

The Tweet: “add something”

X has always felt like a global market square, and we Nigerians have never been shy about bringing our troubles to the world’s table.

One post by Dr Mel on X triggered a firing of commuter frustrations, drawing more than 300 direct replies and hundreds more in sub-comments.

Within hours, thousands were sharing their own experiences. How drivers accept rides at one price only to call before pickup, insisting the amount “can’t work”, so you need to add more if you want the ride to go on as agreed on the app.

One reply summarised the collective mood of commuters: “…You think you’ve booked peace, next thing driver dey try run you street.”

“Especially when you’re coming back from the club, bro—Calabar Bolt drivers are evil,” another wrote, while someone else added, “That’s their new thing in Calabar.” But this isn’t just happening in Calabar, and apparently this isn’t as new as it might seem (I’ll get into this later, so stay with me).

People are getting frustrated with the fare flipping. A large section of the so-called “Twitter NG” came for drivers; the platforms and the think pieces and shallow solutions came in, some hitting the target, others being way off—from “better screening” to “unprofessional and greedy service providers”.

The drivers, or those well-acquainted with drivers, came out pointing to the economics that most passengers never see.

One user explained, “Be informed Bolt takes 25% of each trip; the cost of fuel and car repairs is huge. Any car owner will understand.” Another added that, at times, the cut could even be higher than 25%. A self-identified driver wrote, “If we work with Bolt’s prices, we’ll run into debt.”

In a working market, this should just mean that drivers would switch to a platform that allows them to set rates that they themselves are comfortable with, right? Enter inDrive.

However, even on inDrive, the stories ironically persisted. Drivers would set a price, then call to renegotiate before pickup or the ride itself begins.

That’s where another round of suggestions came in: What about reporting these drivers? Now, there were a couple of users who claimed to have filed complaints immediately, while others held back.

There’s also the question of whether reporting actually achieves anything and, if it does, the reluctance to ruin someone’s livelihood over “something avoidable”. As one X user put it, “Even if you report till tomorrow, they won’t ban drivers…they’re short of drivers as it is.”

For most X users, the echoing charge to drivers was, “If you can’t hold the offer, don’t accept it.” However, the “drivers’ union” on X insisted that it’s not that simple. Because turning down too many trips gets them penalised, most drivers just accept and sort the price out after.

In that case, you could give the drivers on platforms like Bolt and Uber that allowance, right? They do not set the prices themselves and are yet to make that transition to rate-setting on platforms like InDrive. But when ‘inDrivers’ seem to be on the same roll, the irritation is clearly understandable.

Passengers just want to see a certain price on the ride-hailing app and know that’s what it’s going to cost them to get there. Meanwhile, drivers just want a price that satisfies them and is worth the cost.

So let’s see if the unseen ‘economics’ drivers complain about should lead to a price review by the hailing platforms themselves. Here come the facts behind the screens.

Inside the Numbers: What Drives the ‘Add Small’ Economy

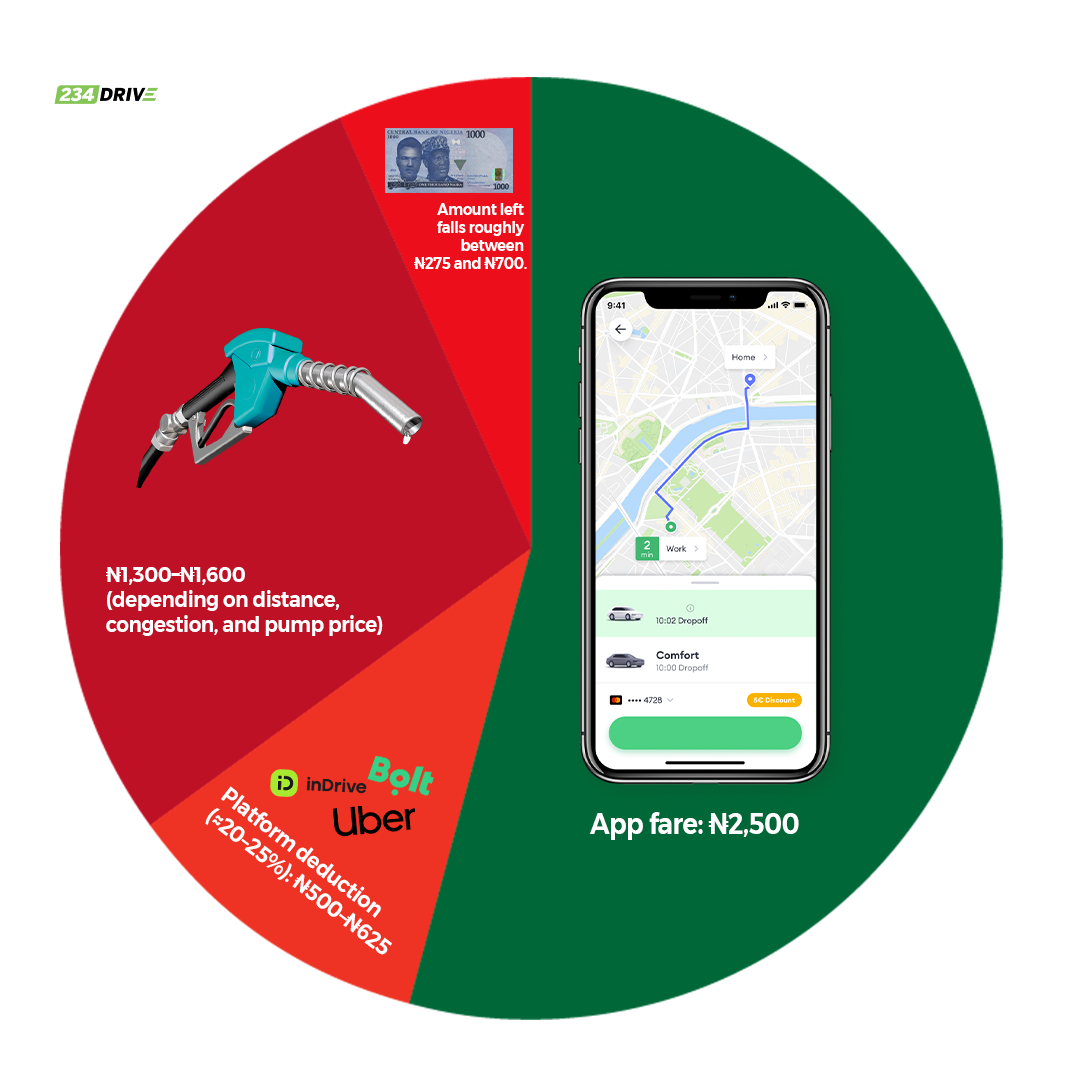

Starting with platform fees, Uber’s help pages say its service fee varies per trip (I didn’t even know this myself, and I’ve used the Uber app multiple times), but it generally hovers around 25% of the upfront price.

InDrive, on the other hand, works differently. Its commission is usually about 9.99%, though some reports mention 9.5%, and in certain areas like Abuja in peak hours, it has introduced a 0.1% service fee to help drivers earn more.

Bolt states plainly that it charges 20% commission in Nigeria. Admittedly, all this sounds very pro-driver. Moreover, the platform’s pricing still piles on costs that hit harder every year: fuel that’s far pricier than it used to be (and still unstable), plus inflation that punishes spare parts and repairs.

It’s worth noting that since Nigeria moved away from fuel subsidies, pump prices have stayed high, closer to that ₦1,000 per litre mark than the nation could have fathomed. Even around late 2024, petrol was roughly ₦998–₦1,030/litre in Lagos and Abuja as market pricing took hold.

These macroeconomic pressures always find their way into the final cost of almost everything in Nigeria, not to mention the transportation sector itself, especially in cities where demand is thinner and return trips are rare.

This opens the door for us to talk about the hidden part of every trip, the “deadheading”. That’s the unpaid distance or time between drop-off and the next pickup, or the run to reach you in the first place.

No passenger onboard, its real cost almost invisible to the rider, and the miles (or kilometres) all add up. Combine that with high fuel and platform fees, and you start to understand some of the drivers’ logic.

Here’s a simple example using the 20–25% rates:

Even Lagos, as busy as it is, has its low-demand pockets. If a drop-off lands in one of those areas, the driver’s real running cost extends beyond the kilometres you paid for to include the extra kilometres to the next pickup, driven empty.

An InDrive driver named James put it this way: “If the destination will leave me stranded, I’ll ask for more upfront or we cancel. Riders hate mid-trip surprises, but some will agree if the logic is stated plainly before ignition.”

Sometimes, the familiar “abeg add ₦500–₦2,000” might not be greed but a small buffer against those empty kilometres that the app doesn’t factor in.

Geography and Demand Gaps: Lagos Isn’t Everywhere

While going through the post on X, I noticed a trend, one that at first seemed like people exaggerating for clout. But the more I scrolled, the more often it showed: there was a sizeable difference in how these platforms operated in Lagos and outside of it. The tone from Lagos-based users leaned toward a budding irritation; from those in other states, it was more of an accepted fate.

To have a proper grasp of this trend beyond the tweets, I decided to do some on-the-ground digging at the perfect place to seek the opinions of Nigerian youths in real time: the NYSC campgrounds.

When I asked interviewees about their experience in Lagos, most described higher prices but smoother experiences. Drivers were generally more professional, cars were cleaner, and the use of air conditioning was standard without argument for the Uber and Bolt rides—some did mention that you had to remind the InDrive drivers that their cars had ACs. Princess, a recent graduate from the University of Lagos mentioned she was “usually kinder to the drivers in Lagos” because “they keep their cars cool and the ride comfortable.” The main issues were traffic and surge pricing—but at least, she said, “you know what to expect.”

In Ibadan, however, the tone changed entirely. Folashade, from Osun state, when narrating her Ibadan experience, flatly said, “the price is never enough for them.” A ₦3,500 fare could become ₦6,000 before the ride even began. Ochanya and Suki, both having schooled in Ibadan, highlighted something similar, if not exact, saying nine out of ten rides came with a request for more money—sometimes before pickup, sometimes mid-trip. And even after bargaining down those requests, the drivers would still ask for extra payment just to turn on the AC. “Those that have AC will tell you to pay if you want them to use it,” Suki said.

The sense of entitlement, she added, often overshadowed the service itself: “The cars are dirty, and most smell. If it was at least comfortable, maybe it would make sense but it’s like you in a Micra.”

Even InDrive didn’t solve the problem. One frequent user said drivers would accept her offer on the app but still call afterward to ask for more, saying it “felt like a setup.”

A driver who works across Ogun and sometimes Lagos, and chose to remain anonymous, confirmed it happens often. He explained that many drivers accept trips quickly so they don’t lose them, then call the rider to renegotiate for a little extra once the booking is locked in.

Another common tactic used by drivers on the InDrive platform is slightly undercutting the price. By inputting trip details fast on Bolt or Uber, drivers can bring the fare close enough to look fair but still make something extra. It’s a quiet way to maximise profit while staying just under Uber and Bolt’s system thresholds.

Back at the NYSC camp, when answering the same question of reporting drivers, the responses mirrored the same pattern seen online: most people simply didn’t bother. Some said they didn’t think Bolt or Uber would take action; others admitted they just didn’t want to “ruin someone’s hustle”.

Only one interviewee, Naomi, had ever actually filed a report—and it wasn’t even about the money. Her case involved something far more serious: the man who came to pick her up didn’t match the image of the driver shown on the Bolt app. “It only happened once,” she mentioned, “but I reported it immediately as it’s a safety issue.”

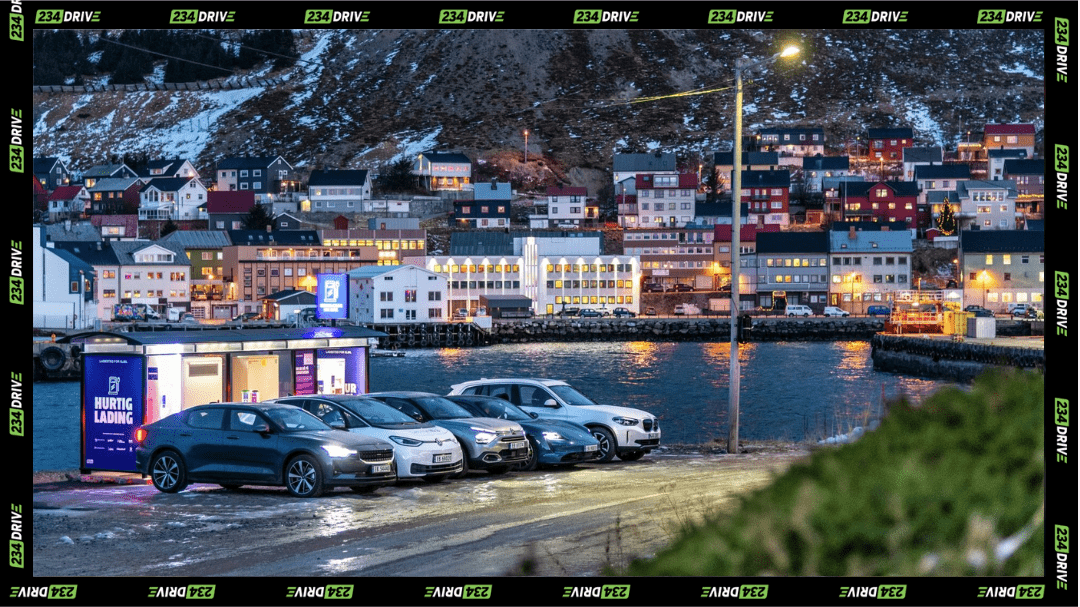

Interestingly, Naomi also shared her experience outside Nigeria using Uber—in London—which was the polar opposite. When asked about the “add more” situation, she shook her head, saying, “You can’t pay cash,” before adding, “So there’s no way for someone to ask you to add anything. Everything is already handled in the app.”

From Lagos to Ibadan to Ogun, the pattern is clear: geography and even estate area change everything. The same app is used differently once you cross state lines in Nigeria.

Lagos density is its own price signal: shorter wait times, a greater chance of the next ping, and better odds of a return trip from almost anywhere. That doesn’t make the economics easy—but it does reduce the deadhead penalty. Outside Lagos, where demand density isn’t as high, the situation worsens.

Pricing models that treat every kilometre as equal can feel fair on a spreadsheet but would be unfair in actuality. Most times, that’s where human negotiation comes in and the driver reads the map before calling to say, “This trip you’ll be paying for two in one, going there and me coming back empty.”

Trust, Negotiation, and the Nigerian Way of Doing Money

People who have booked rides in multiple states (including Lagos) know service in any other state isn’t going to be like Lagos. Demand is lower, routes are longer, and trips from busy areas to quieter ends often leave drivers stranded. Still, riders said their frustration comes from the back-and-forth over the price—bargaining that happens outside the app instead of within it.

Nigeria runs on negotiation, so it’s no surprise that both sides fall back on that instinct. But what’s acceptable in a market feels misplaced in a supposedly cashless, automated system.

Princess and Folashade admitted that they understood why drivers in low-demand areas might ask for more. Yet both said they’d rather the app reflected the true cost upfront. “If the app says ₦5,000 instead of ₦3,500, I’d trust that,” Princess said. Suki also agreed with this, saying she’d prefer to decide on the spot whether to continue with the ride before the driver got there than to argue mid-trip.

Naomi, who called Nigeria’s tipping habit “our own version of appreciation”, echoed the thought. She believed Uber should automatically show when a trip runs longer or involves extra waiting.

Every interview ended with the same conclusion: people trust the platform, not the negotiation. If Uber, Bolt, or InDrive clearly displayed the hidden factors—regional pricing, long pickups, or traffic-time surcharges—riders would pay with way less resentment.

The Platform and Policy Blind Spot

E-hailing in Nigeria still operates in a bit of a grey zone. Platforms like Uber and Bolt adjust prices with surge rates, zones, and minimum fares, but most states have no clear rules guiding how these services should work. Only Lagos has an official e-hailing policy that covers licensing, data sharing, and penalties. Because of this, drivers outside Lagos have even less stopping them from taking a trip “off-app” or quietly renegotiating once the passenger is in the car.

These offline trips, where both parties agree to cancel the app ride and pay in cash or transfer, may seem harmless, but they remove all app protection: the tracking, the insurance, and no record if something goes wrong. It’s a loophole created and exploited by weak rules and pricing that ignores local realities.

Drivers often defend it as survival: “The app price no reach, and the commission plenty.” For many, it’s how they cover fuel and long return trips. Still, the fix is simple. Platforms should price what the map really costs, adding clear adjustments for long pickups or low-demand areas. A short note like “₦600 added for return risk (low-demand zone)” would make sense to riders.

States beyond Lagos could also adopt basic, flexible rules—driver ID checks, complaint systems, and transparent pricing—without stopping surge pricing. It’s not about control; it’s about fairness, safety, and trust for both sides.

Closing: Price the Road, not Just the Ride

After reading through the hundreds of tweets and speaking to both drivers and riders, one thing became clear: nobody wants to be cheated.

Riders insist that the app prices are fair because they come from the service platforms. Drivers argue the opposite—that those same prices are unfair and unsustainable. It’s like a tennis match where both Djokovic and Nadal complain that the other has too much room to serve before the game even starts. That’s where the ATP—in this case, the ride-hailing platforms—should step in.

If only one side (drivers or riders) complains, it barely makes a dent. But when both raise concerns about fairness and trust, the system itself demands a review. Yet, many riders still believe it’s a driver-versus-platform issue—“let them sort it out,” as one X user put it. The trouble is, until that happens, the off-app negotiations and quiet “add something” culture will continue.

Of course, there’s also the human element—greed. The saying “human wants are limitless” holds true here. Even if the platforms fix their pricing algorithms, a few drivers will still ask for more, because there will always be someone willing to pay.

For riders who want to avoid such scenarios altogether, paying directly through the app helps. It removes the moment where a driver can nudge for cash “before” the trip ends.

When I first started reading the comments, I marvelled at them because I had never experienced such. But this soon changed on my first trip to the NYSC camp in Lagos. Mid-ride, the driver turned and said, “Bros, the money wey I put for this trip no favour me at all. You go help me add something, abeg.”

That’s when it clicked. Many riders have heard some version of that same request, “Make you help me add small,” or “I no know say na that place oh, I for no go for that price.” Before it gets mixed up, these requests are not tips—it’s a pre-service negotiation; it doesn’t matter if it’s formally or emotionally done. You don’t tip a waiter before your food is served, and no waiter says, “This dish is heavier than what I carry to this side of the restaurant, you’ll add small money.” Understanding that difference matters.

In the end, we’re all moving through the same tough economy—both rider and driver. Everyone’s trying to survive. The least we can do is approach each other with honesty: no exploitation, no manipulation, just fair exchange. Because the moment trust breaks, the road—no matter how smooth—starts to feel longer for everyone.