A Nigerian-led electric vehicle manufacturer has just proven that Africa’s EV market isn’t a future possibility—it’s here now. Kemet Automotive, co-founded by former Jaguar Land Rover designer Nissi Ogulu and entrepreneur Rui Mendes Da Silva, has crossed 10,000 pre-orders following the November 2025 unveiling of its first production-ready vehicle design. The milestone represents one of the strongest early validations for an African-made EV brand to date, signalling genuine continental appetite for homegrown sustainable transport solutions and marking the company’s shift from concept phase into full-scale manufacturing planning.

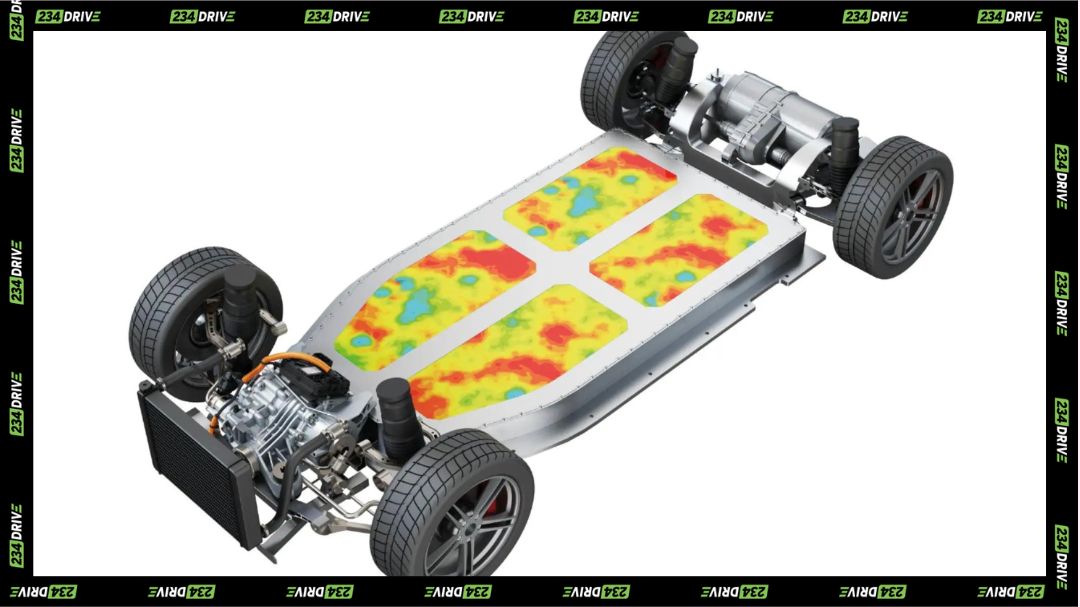

The surge in demand comes as Africa grapples with escalating fuel costs, worsening urban air quality, and a growing middle class frustrated by imported vehicles that weren’t designed for local conditions. Kemet’s approach differs fundamentally from simply rebadging foreign EVs or importing Chinese models. The startup is engineering from the ground up for African roads—designing for higher ground clearance to handle rough terrain, robust battery thermal management for extreme heat, and affordable serviceability in markets where Tesla service centres don’t exist. With Africa’s urban population projected to hit 1.4 billion by 2050, Kemet Automotive is positioning itself at the centre of a multi-billion-dollar addressable market that legacy automakers have largely overlooked.

Kemet’s design philosophy, called “Functional Sculpting,” rests on three pillars: durability for Africa’s varied terrains, emotional resonance that evokes pride and reflects African cultural identity, and timeless form that avoids trend-chasing aesthetics. Nissi Ogulu, who worked on the fifth-generation Range Rover before returning to Africa to launch Kemet, stated the vision bluntly in the company’s announcement: “Kemet is building vehicles that inspire pride and deliver real performance. We want Africans to see that world-class innovation can come from here—and lead globally.” That ambition isn’t just marketing talk. The pre-orders span multiple African countries, driven by customers who see localised manufacturing as both an economic and cultural imperative.

The company’s vehicle lineup includes the Nandi compact SUV, the Mansa premium SUV, and the Gezo electric tricycle—each tailored to specific use cases across the continent. The Gezo targets last-mile delivery and urban mobility in dense cities like Lagos and Nairobi, where narrow streets and traffic congestion make traditional vehicles impractical. The Nandi aims at the mass market with pricing targeted around $20,000 to $25,000, positioning it competitively against popular internal combustion models like the Toyota Corolla and Honda CR-V. The Mansa serves the premium segment, offering Range Rover-level refinement with African design sensibilities. Early concept imagery reveals bold surfacing, high beltlines for commanding visibility, and integrated roof racks—practical details that acknowledge how African consumers actually use vehicles.

What sets Kemet apart strategically is its partnership with Africa Design School in Cotonou, Benin Republic. The collaboration creates structured training programmes for young African designers and engineers, building a sustainable talent pipeline whilst embedding continental aesthetics into global automotive design. This isn’t charity—it’s infrastructure building. By training the next generation of mobility innovators, Kemet ensures it won’t face the talent shortages that have hampered other industrialisation efforts across the continent. The initiative also positions Africa not just as a consumer of technology, but as an innovator and exporter.

Kemet’s production strategy involves localised manufacturing across multiple African countries, with Nigeria and Benin identified as initial manufacturing hubs. This approach reduces import duties, creates jobs in fabrication and assembly, and keeps more economic value on the continent. The company secured pre-seed funding in 2023-2024 and has been actively engaging investors and partners for the next phase—factory buildout, supply-chain development, and scaling production towards its earlier guidance of 2027 launches. Economic impact projections are substantial: thousands of jobs in manufacturing, supply chains, and technology sectors, plus reduced reliance on imported fossil-fuel vehicles that drain foreign exchange reserves.

The timing couldn’t be better. Global automakers are finally waking up to Africa’s potential, but they’re moving slowly. Tesla’s presence on the continent is gradually growing with an office in Morocco. European and Chinese manufacturers are testing the waters with limited dealer networks and minimal localisation. Kemet’s first-mover advantage lies in deep market understanding—knowing that African buyers prioritise reliability over flashy tech, that service networks matter more than over-the-air updates, and that vehicles must handle dust, flooding, potholes, and heat extremes simultaneously. Whilst foreign automakers run focus groups, Kemet’s founders have lived these realities.

Compare this to India’s EV rollout, where local manufacturers like Tata Motors and Mahindra went from concept to mass production in under three years by focusing on affordability and local infrastructure compatibility. Tata’s Nexon EV launched in 2020 and captured 70% of India’s EV market within 18 months by pricing aggressively and building charging networks in tier-two cities. Kemet is following a similar playbook—prioritise local needs, scale fast, and force foreign competitors to play catch-up on your terms. The difference is that Africa’s fragmented regulatory environment and infrastructure gaps make execution harder, but the market opportunity is proportionally larger.

This marks the shift from EV hype to fleet-scale operations in Africa. The question now isn’t whether Africans want EVs—the 10,000 pre-orders answer that decisively. The question is whether African governments will treat clean mobility infrastructure like the public good it is, fast-tracking charging networks, offering tax incentives for local manufacturing, and creating regulatory frameworks that favour regional champions over foreign imports. Kemet has proven market demand exists. The next move belongs to policymakers: will they accelerate Africa’s transition to sustainable transport, or let foreign automakers capture the value once again?