Germany’s new chancellor has just asked Brussels to rewrite the rules on Europe’s combustion engine ban—and unlike previous industry grumbling, this time the European Commission sounds willing to negotiate.

In late November 2025, Chancellor Friedrich Merz sent a formal letter to European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen requesting explicit exemptions to the EU’s 2035 phase-out of new combustion-engine vehicles. Berlin wants permission to continue selling plug-in hybrids, range-extender electric vehicles, and “highly efficient” conventional engines beyond the deadline, arguing that a hard cut-off is unrealistic given slow EV adoption, Chinese competition, and the need to protect German automotive jobs. The request follows a coalition agreement uniting Germany’s government behind industry concerns and comes with potential sweeteners including new subsidies up to €5,000 for EVs and hybrids with high EU-made content. The European Commission plans to announce its automotive package review on 10th December 2025, with Vice-President Stéphane Séjourné already signalling openness to “flexibility” in implementation. The UK’s separate Zero Emission Vehicle Mandate—which requires 28% of new car sales to be fully electric in 2025, rising to 100% by 2035—remains unchanged for now, though shared pressures on manufacturers operating across both markets could eventually spark parallel debates in Britain.

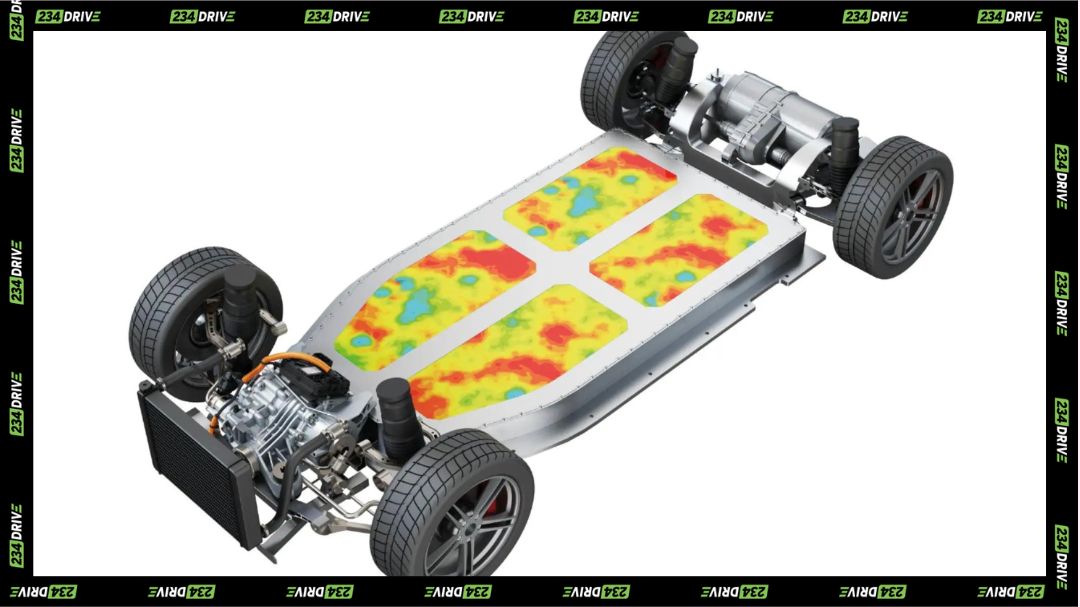

The EU’s 2035 regulation, adopted in 2023, mandates 100% CO₂ reduction for new cars and vans from that year, effectively banning any vehicle with tailpipe emissions. The rule already includes a narrow e-fuels loophole secured by Germany in 2023, allowing vehicles running entirely on synthetic fuels, but current demand and infrastructure for e-fuels remain negligible. Merz’s November 2025 push goes much further, seeking to preserve three categories of combustion technology beyond the deadline: plug-in hybrids with substantial electric-only range, range-extender EVs that use a small petrol engine purely as a backup generator, and highly efficient conventional engines potentially running on biofuels or optimised for minimal emissions. The chancellor framed this as “technology neutrality,” arguing it is “more opportune and pragmatic to invest more effort and money in the development of efficient, hybrid systems that will combine the best of the world of internal combustion engines and electric mobility.”

Germany’s position stems from acute industrial anxiety. Volkswagen, BMW, and Mercedes-Benz have announced factory slowdowns and job cuts as EV sales growth has plateaued well below targets, whilst Chinese manufacturers including BYD and Nio have captured growing European market share with cheaper electric models. The VDA automotive association has lobbied intensively for regulatory relief, warning that a rigid 2035 deadline could devastate German manufacturing if consumer demand for full battery electric vehicles doesn’t accelerate. The coalition agreement uniting the CDU/CSU (traditionally pro-industry) with the SPD and Greens (historically more climate-focused) represents a significant political shift, with even Germany’s environmental parties reluctantly accepting some compromise to preserve industrial jobs. Proposed subsidies of up to €5,000 for EVs and hybrids containing high EU-made content would attempt to counter Chinese competition whilst maintaining some pressure toward electrification.

The European Commission’s apparent willingness to negotiate marks a notable change in tone. When Germany first secured the e-fuels exemption in 2023, it faced fierce resistance from other member states and environmental advocates who viewed any loophole as undermining climate commitments. Now, with multiple manufacturers struggling to meet interim CO₂ targets and consumer resistance to EVs proving more stubborn than anticipated, Brussels appears ready to consider broader flexibility. Vice-President Séjourné’s comments ahead of the 10th December announcement suggest some form of compromise is being crafted, though the specifics remain unclear. France and Spain reportedly oppose weakening the 2035 target, arguing that wavering now would discourage the investment and infrastructure build-out needed for full electrification. Italy and several Eastern European states have previously sought reviews, creating a complex negotiating landscape.

Environmental organisations have responded with alarm. Transport & Environment, one of Brussels’ most influential green advocacy groups, criticised Germany’s push as clinging to “outdated” technology and urged alternative measures including mandatory electrification targets for company fleets—currently 75% of new car registrations in many European markets. The organisation argues that allowing hybrids beyond 2035 would lock in continued fossil fuel dependency, undermine battery manufacturing investments already made across Europe, and send confused signals to an industry that needs regulatory certainty to plan billion-euro production commitments. The debate mirrors broader tensions between climate ambition and industrial competitiveness that have intensified as the EU’s Green Deal collides with economic headwinds and geopolitical rivalry with China.

The UK operates entirely outside this regulatory framework post-Brexit, but the pressures are strikingly similar. Britain’s Zero Emission Vehicle Mandate requires manufacturers to ensure 28% of new car sales in 2025 are zero-emission vehicles—almost exclusively battery electrics, since hydrogen remains commercially negligible. That percentage rises progressively: roughly 33% in 2026, 80% in 2030, and 100% by 2035. Plug-in hybrids do not count toward the ZEV quota, meaning manufacturers must sell sufficient full battery electric vehicles to avoid fines of £15,000 per vehicle shortfall. Current UK BEV market share sits around 20-25%, well below the 28% target, putting significant pressure on brands to either discount electric models heavily, restrict petrol car availability, or pay penalties and pass costs to consumers.

Germany’s campaign has no direct legal impact on UK policy, but it highlights challenges shared across European automotive markets. Volkswagen, BMW, and Mercedes sell heavily in Britain through the same dealer networks and often from the same production lines supplying both markets. If the EU grants hybrid exemptions beyond 2035, it would reduce pressure on shared manufacturing capacity and potentially embolden UK manufacturers and their trade associations to seek parallel flexibility. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders has previously raised concerns about the ZEV Mandate’s trajectory, though government ministers have thus far maintained the existing schedule. No changes have been signalled as of early December 2025, with officials emphasising commitment to the 2035 full phase-out and ongoing investment in charging infrastructure.

The politics differ meaningfully between Brussels and Westminster. The EU’s 2035 ban emerged from a complex negotiation among 27 member states with wildly varying automotive industries and climate ambitions, making subsequent modifications nearly inevitable. The UK’s ZEV Mandate represents domestic policy that’s already been delayed once—the previous government pushed the full ban from 2030 to 2035 in 2023—and further backtracking would carry political costs for a government that has positioned climate leadership as central to its industrial strategy. But if Germany succeeds in securing hybrid exemptions and other EU states follow, British policymakers will face growing pressure from an industry arguing that regulatory divergence puts UK manufacturing at a competitive disadvantage.

The 10th December European Commission announcement will clarify whether Germany’s push results in formal policy changes or merely softer enforcement rhetoric. If Brussels grants meaningful exemptions for plug-in hybrids and range-extenders, it would represent a significant retreat from the EU’s most ambitious automotive climate policy and potentially reshape the global transition away from combustion engines. If the Commission holds firm, Germany may face the choice between accepting industrial pain or intensifying pressure through coalition politics and potential legal challenges. Either way, the debate has shifted from whether the 2035 target is technically achievable to whether it’s politically sustainable—and that question resonates far beyond Germany’s borders.