Nigeria is finally putting its engineering where its mouth is, signalling a profound industrial pivot as the state-led pursuit of driving Nigeria’s turn towards domestic vehicle manufacturing moves from political rhetoric to the actual tarmac. This shift is marked by the recent arrival of the nation’s first fully designed and assembled electric vehicles, suggesting that the era of relying solely on imported technology may be nearing its end.

The National Agency for Science and Engineering Infrastructure, under the decisive leadership of CEO Khalil Suleiman Halilu, has officially pulled the curtain back on a domestic mobility bid involving a designed and assembled electric sedan and pickup truck. This rollout is not merely a symbolic gesture but a commercial venture with units estimated to cost around N80 million, as the agency targets a significant reduction in the nation’s reliance on expensive fossil fuel imports. By aiming for a localisation rate of up to 70 per cent for components, the initiative seeks to slash the costs of these vehicles by nearly a third compared to their imported counterparts, potentially making sustainable transport a viable reality for Nigerian fleets and logistics firms.

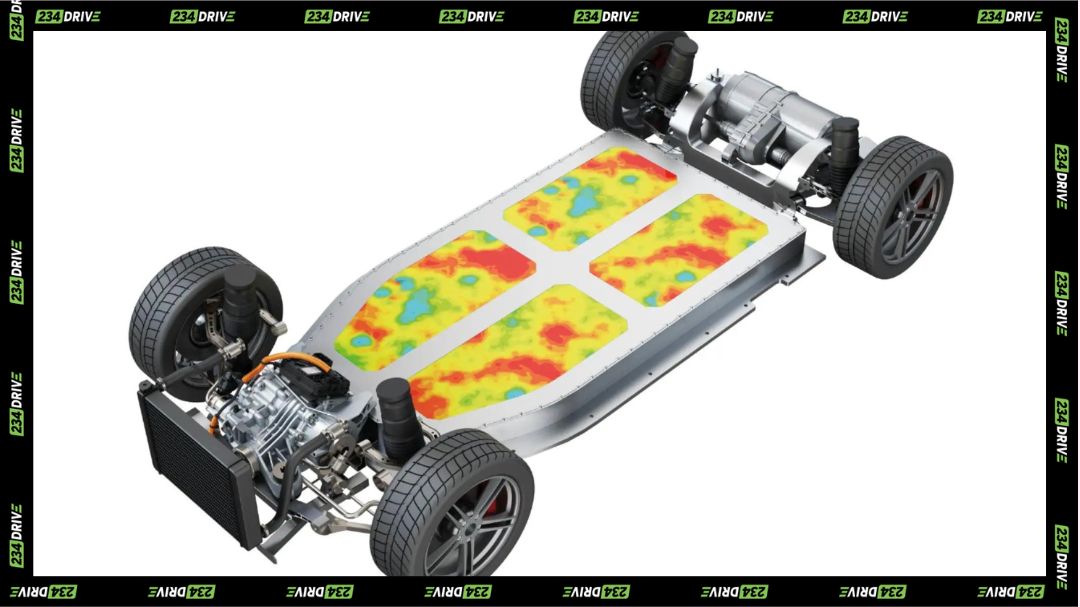

These vehicles represent a radical departure from traditional automotive architecture, swapping out complex internal combustion engines for high-efficiency electric motors powered by advanced lithium-ion battery packs. The designs are specifically tailored to the nuances of West African terrain and infrastructure, featuring hybrid configurations that include fuel backups to alleviate range anxiety while charging networks are still being developed. Beyond the core powertrain, the vehicles boast modern refinements such as regenerative braking systems for energy recovery and integrated touchscreen infotainment suites, ensuring that local innovation does not come at the expense of global consumer expectations.

The project operates as a sophisticated ecosystem where the agency acts as the primary architect and assembly lead, while the government provides the necessary Customs monitoring platform and regulatory framework to manage large-scale commercial distribution. This structure ensures that while the state handles the heavy lifting of research and development, the ultimate management and scaling of the fleet remain agile and market-driven. The agency handles the design, the local workforce manages the assembly, and the policy-makers facilitate the adoption through infrastructure development.

This move signals a fundamental shift in Nigeria’s industrial strategy, prioritising the “three Cs” of commercialisation, collaboration, and competitiveness to ensure that home-grown technology can survive in a cut-throat global market. By focusing initially on high-impact sectors like electric tricycles and delivery services, the agency is securing a steady demand loop that justifies the massive investment in local lithium-ion battery factories. This strategy also includes ambitious plans for converting millions of existing vehicles to cleaner energy alternatives, supported by a state-led gas monitoring system, securing a foothold in the green economy.

While global giants like China and the United States are already decades into their electric transitions, Nigeria’s entry is remarkably strategic, focusing on the immediate practicalities of an emerging economy rather than just high-end luxury consumerism. Nigeria is currently playing catch-up despite a recorded rise in adoption, but the speed at which the agency has moved from concept to functional prototypes suggests a sense of urgency that has been missing from previous industrial policies. The contrast is sharp; while other nations focus on private ownership, Nigeria is looking at the fleet operations that power the economy.

Regionally, the pace is quickening, with Burkina Faso’s Itaoua brand having already established a presence through international partnerships to prove that African-made EVs are more than a niche curiosity. These regional competitors have shown that clearing certifications and moving from launch to full-service deployment can be achieved in a matter of months when policy and private investment align. Nigeria is now entering this regional race with a focus on deep localisation rather than just the assembly of foreign-made kits.

Nigeria’s industrial history is littered with grand declarations that stalled at the factory gates, but the firsthand testimony of early test drivers provides a rare sense of optimism. Ezinne, a local banker who participated in the initial trials, noted that the silence and refinement of the vehicles significantly challenged her own scepticism regarding the quality of Nigerian manufacturing. This tangible proof of concept, showing how these vehicles will revolutionise transportation, suggests that the infrastructure for a wider rollout is already being built beneath the surface.

This milestone marks the definitive shift from speculative hype to fleet-scale operations, yet the ultimate success of Nigeria’s green transition remains tethered to the government’s willingness to commit to long-term charging infrastructure and tax incentives. As these vehicles begin to navigate the streets of Lagos and Abuja, the question for policymakers is no longer whether Nigeria can build the future, but whether they will provide the regulatory fuel needed to keep it moving. Should regulators treat charging networks like public infrastructure to speed adoption, or leave it to the slow crawl of the private market?