Somewhere between earnings calls and internal strategy decks, $55 billion quietly disappeared. While it didn’t happen all at once, over the past twelve months, automakers across the U.S. and Europe rolled back their EV plans built on assumptions that their movement would stir a self-sustaining wave. There was a wave, but what followed still wasn’t big enough for the governments and automakers to ride upon.

The charges didn’t come from one bad quarter but also future commitments they had hoped to build upon, but expectations drifted further from what the market was actually doing. Take Stellantis, which booked about $26.2 billion after reshaping its lineup and dialling back volume assumptions, particularly in the U.S.—a market where the group still leans heavily on Jeep and Ram, two of the most profitable names in pickups and SUVs. Its CEO summed it up plainly.

“the industry moved faster on ambition than customers did in reality.” – Antonio Filosa

Ford Motor Company, a company that has reinvented itself more than once over a century of carmaking, followed with a $19.5bn writedown. Several planned EV models were dropped, and the American maker paddled back toward its hybrids and combustion vehicles—more in flow with its history of adapting to where demand actually still sits.

At General Motors, the pullback came with a $6bn charge, much of it tied to supplier payouts after cutting planned EV volumes. The impact touched familiar nameplates under Chevrolet and Cadillac, brands GM had positioned at the centre of its electric push. Scaling back meant unwinding commitments that were already deep into the supply chain.

The same pressure showed up in Europe, where Volkswagen absorbed a roughly €5.1bn hit after Porsche delayed some electric launches and extended the life of combustion and hybrid models

Nonetheless, the EV story doesn’t begin and end in Detroit or Stuttgart. Outside the U.S. and Europe, there are two other forces shaping how this transition plays out—one of which most readers can already guess. This player clears its competition through cost, scale, and speed. And they are setting the price floor everyone else now has to live with. The answer, of course, is China—and what has been happening recently is largely being decided there.

From Carmakers’ Side Projects to Industry Dominance

For years, China built the world’s products before building its own brands. It mastered manufacturing at scale, learned fast, and moved up the value chain. The same pattern played out in electric vehicles. Before China became the global EV heavyweight it is now, it hosted the rise of Tesla. When Tesla opened its Shanghai Gigafactory in 2019, it gained speed, lower costs, and direct access to the world’s largest car market, but China wasn’t just assembling cars—it was studying Tesla’s playbook and working on its tactics to dominate the game.

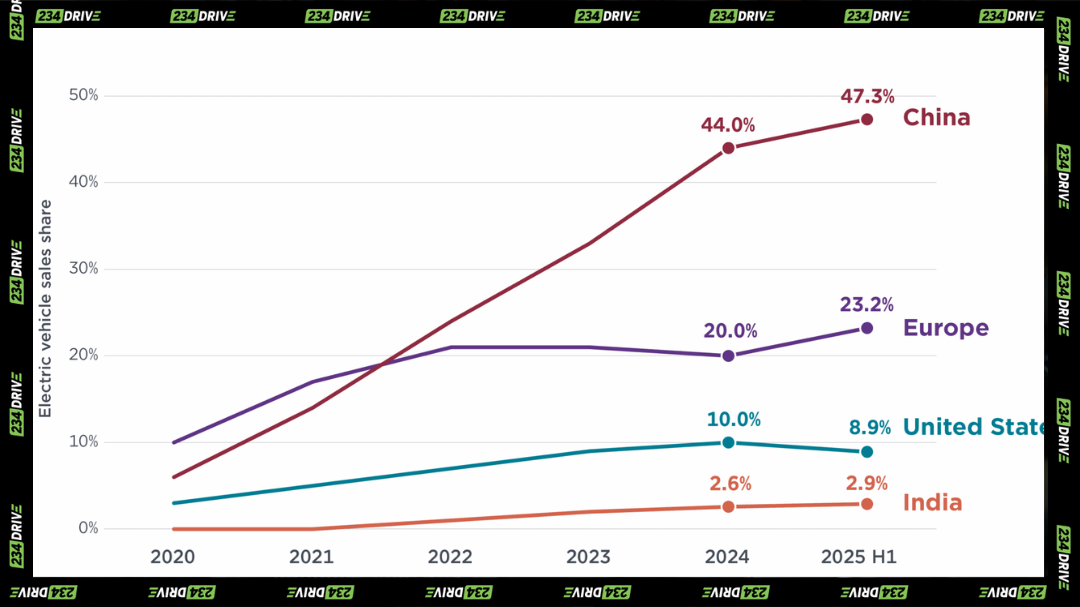

There isn’t really a debate about whether EVs work or people want them. They do. Global electric car sales passed 17 million in 2024, making up more than 20% of all new car sales worldwide, according to the International Energy Agency. China alone accounted for over 11 million of those sales, with electric cars approaching half of all new vehicles sold in the country.

So the demand and practicality are there, and the global conversation has now shifted to control—on price, the battery supply chain, the charging network, and mass scaling. The focus has changed from the early years, where carmakers proved EVs could compete with combustion engines, to the next phase, which rewards whoever can produce them cheaper and faster than everyone else. Right now, that country is China.

To better understand how the current tension took shape, it helps to walk through the EV timeline itself. So far, the journey can be framed in four distinct stages—each one building momentum, shifting expectations, and setting up the pressures we see today.

Stage 1: Tesla Proved People Actually Want This

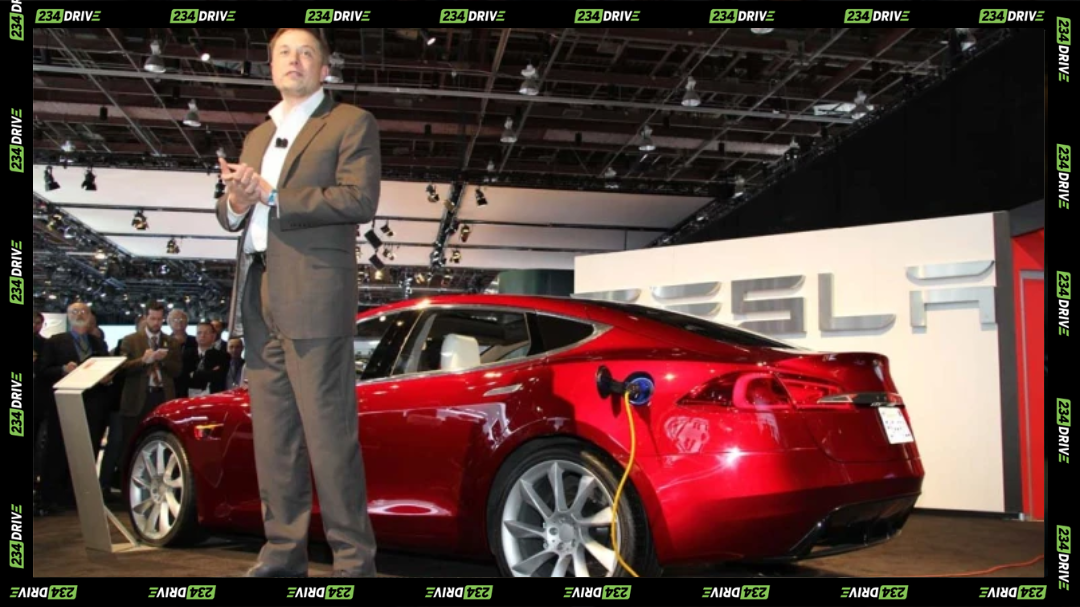

Elon Musk unveils the Tesla Model S, redefining electric cars with performance, range, and bold ambition. | Source: nbcnews

When Tesla launched the Model S in 2012, it forced the industry to rethink what an electric car could be. The car moved quickly, looked premium, and travelled far enough on a charge to make daily life practical. That mattered. Until then, most EVs felt like carmakers’ compliance projects. Tesla made them aspirational, then followed up with something just as important: building chargers.

The Supercharger network began rolling out in 2012. That decision changed the conversation. Charging stopped being a question left to governments or third parties. Tesla treated infrastructure as part of the whole product. Drivers could see stations along highways. They could plan trips. Long-distance travel became possible without charging gambles when a framework of stations mapped strategic regions.

That change turned range anxiety into more of a planning issue than a deal-breaker. As charging networks expanded, confidence grew. Early adopters stepped in, while the wider market watched carefully. Demand started forming, but excitement alone couldn’t sustain it. Governments were also under pressure to cut carbon emissions and clean up city air. With transport being a major source of CO₂ globally, here was an opportunity to achieve climate targets, so encouraging EV adoption amongst its citizens became more of a responsibility.

Stage 2: China Turns EVs Into an Industrial Machine

Chinese factory workers assemble electric vehicles at scale, reflecting the country’s manufacturing dominance in EV production. | Source: globaltimes

Once policymakers saw demand building due to practicality, governments moved to accelerate it. The United States expanded federal tax credits for EV buyers, and European countries rolled out purchase incentives and climate targets. China moved even more decisively, embedding support directly into industrial policy and production rules.

The government introduced its New Energy Vehicle mandate and credit system, making EV production part of the national strategy. Subsidies, which began in 2009, accelerated the push. Manufacturers did not simply build cars; they built capacity, supply chains, and battery expertise at the same time.

Scale lowered costs as competition pushed manufacturers to operate more efficiently, and battery prices fell faster in China than in Europe or the United States, giving producers the confidence to expand exports aggressively. At this stage, EV leadership began moving from being able to prove concepts to commanding production power, and while the market expanded quickly, that kind of rapid growth inevitably tests what happens when policy support begins to shift.

Stage 3: Subsidies End and the Market Finds Its True Price

The stress test arrived when governments began pulling back support. China ended its national EV purchase subsidies on December 31, 2022, forcing automakers to react quickly. Some absorbed the added cost, others adjusted pricing, with Tesla cutting prices to defend its market share while BYD leaned on its scale and domestic strength, raising prices modestly on select models. Buyers rushed to secure incentives before the deadline, creating a temporary spike in sales, but demand cooled noticeably once subsidies disappeared and price sensitivity became clearer.

Germany followed by ending its EV subsidy program in December 2023 after paying out roughly €10 billion since 2016, underscoring the limits of public funding. In the United States, the rollback and uncertainty around federal tax credits similarly distorted buying patterns, as consumers accelerated purchases before benefits expired, only for demand to soften afterward. Companies could no longer rely on policy alone to support growth; they had to compete on cost and value. This phase revealed who could operate without heavy incentives and reinforced a growing reality: China’s lower cost base gave its manufacturers more flexibility when the safety net of subsidies and incentives disappeared.

Stage 4: Europe Recalibrates While the Industry Resets

China began to pull ahead just as the market started to wobble. While Europe and the United States debated timelines and incentives, Chinese manufacturers scaled production, lowered battery costs, secured supply chains, and priced vehicles aggressively. China became the go-to source for affordable EVs, both at home and increasingly abroad. By 2025, BYD had overtaken Tesla in annual electric vehicle sales.

Chart tracks China’s rising electric vehicle share, outpacing Europe, the U.S., and India from 2020 to 2025 H1. | Source: icct

A dominance that some say triggered political pushback. The EU and the U.S. introduced tariffs on Chinese-made EVs to protect domestic carmakers that struggled to match China’s scale and pricing. At the same time, Western governments had already committed to ambitious transition targets. Consumers, however, did not move as quickly as policymakers expected. After subsidies were reduced and interest rates rose, many buyers drifted back toward combustion engines and hybrids, leaving automakers with rising EV losses.

To avoid further strain, Europe adjusted its approach, allowing more flexibility in its 2035 targets and giving hybrids a larger role in the transition. Meanwhile, China continued expanding into Southeast Asia, Latin America, and much of Africa, pairing vehicle exports with charging-network rollouts, dealership partnerships, and battery supply agreements. In Africa, Chinese EV makers are focusing on regional hubs such as South Africa, Uganda, Rwanda, and parts of West Africa—building charging corridors, supporting electric buses and testing demand before considering local assembly.

The debate has shifted. It is no longer about whether EVs will grow but about who can produce them profitably and at scale.

Final Thoughts

Despite the sheer size of the write-downs, most automakers will absorb the losses and push forward with longer-term plans. The next winners may not be the loudest brands or the ones running the boldest campaigns. They will likely be the companies that control their supply chains well enough to keep vehicles affordable and production steady. Electric vehicles rest on a few core foundations: battery cells, access to critical minerals, power electronics, and software. Batteries depend on lithium, nickel, cobalt, and graphite. Motors require rare earth elements. Power systems need advanced semiconductors. Software connects and manages everything. China secured early access across much of that chain, from mineral processing to battery manufacturing and component scale, while many EU countries still rely heavily on imported raw materials and refining capacity.

The EV timeline also reaches beyond car companies. It influences oil demand, power grids, mining, and refining. In 2024, as EV adoption grew by 13% across China, the U.S., and Europe, oil prices slipped by about 3%, marking a second consecutive annual decline. By 2025, prices weakened further as supply increased and demand growth in China slowed, contributing to an oversupplied market and pushing Brent crude toward the high-$60s range. The effects show up across the energy system.

Policy adjustments in Europe and the U.S. may now give automakers something practical: time. Time to secure more stable access to raw materials, expand battery partnerships, and reduce dependence on a single region. Instead of chasing rapid volume alone, companies can strengthen recycling, diversify sourcing, and improve cost control before the next growth phase.

Governments should also shift focus. Electrifying public transport fleets, such as buses and municipal vehicles, can reduce emissions at scale because these vehicles follow predictable routes and charge from central depots. Expanding urban charging in apartment-heavy areas removes daily friction for drivers. Supporting smaller electric mobility platforms, including two-wheelers and compact city vehicles, lowers infrastructure strain and keeps adoption within reach for more households.