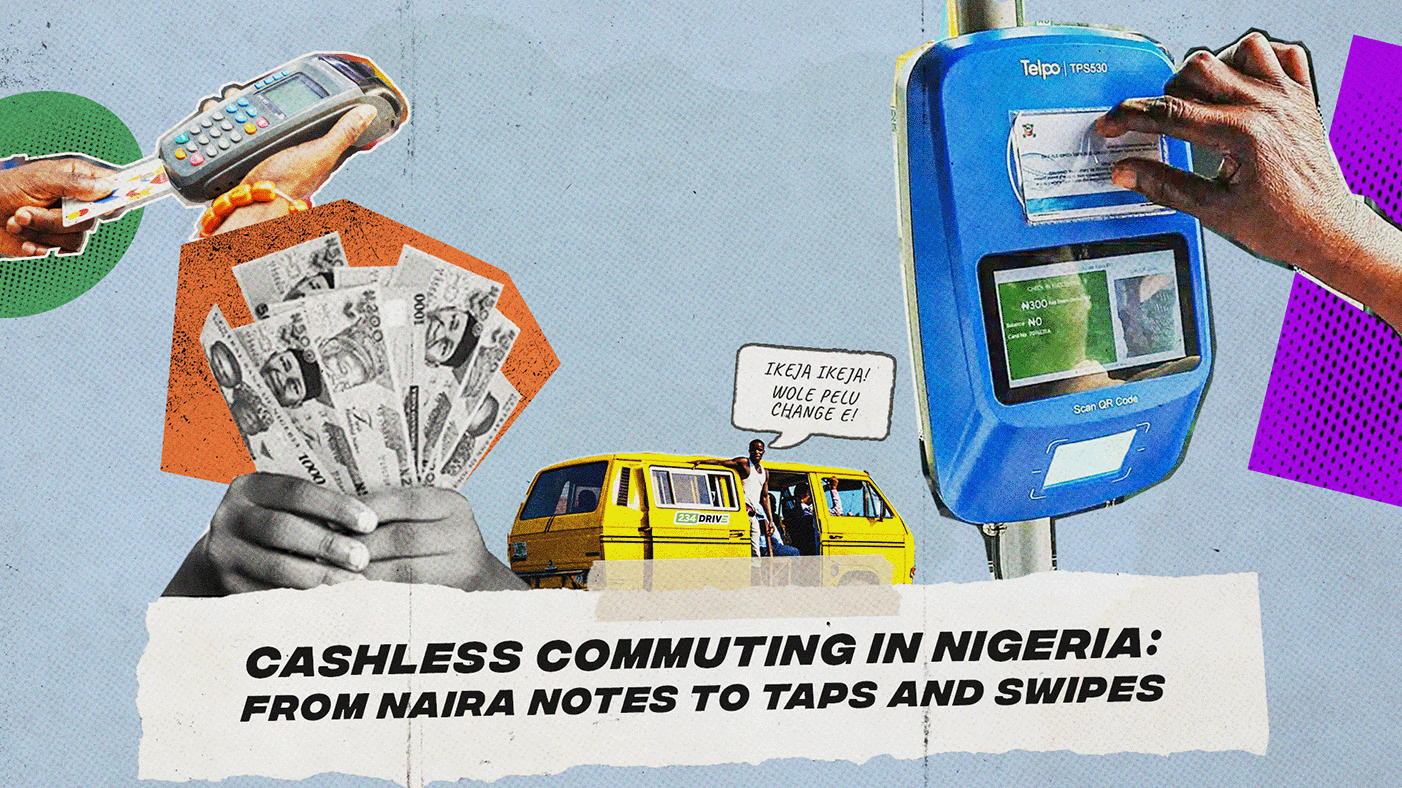

Twenty years ago in Lagos, commuting from Iyana Ipaja to Oshodi wasn’t just about the journey; it required planning. It wasn’t simply about catching the next danfo; you also had to ensure you had the right cash on hand. Conductors would shout, “Wole pelu change e!”, reminding passengers to have exact fare ready, or risk a frustrating argument over change. In Imo State, for example, families gearing up for the Eke market day often entailed a trip to the bank or gathering funds from local ajo savings. Back then, cash was essential for every kind of transaction.

Whether it was traveling from Lagos to Abuja, where you had to buy your ticket with physical naira before departure, or filling up at fuel stations that only accepted cash, currency in hand was a must. Even paying your electric bill meant a trip to the NEPA office to hand in cash. Weekend treats at Mr. Biggs? Dad’s wallet needed to be bursting with naira notes. Cash was the centerpiece of every transaction.

Fast forward to 2024, and things have shifted dramatically. Cash is now just one of many payment options available. A simple trip to buy groceries today often begins with questions like, ‘Cash or transfer?’ and perhaps even more popular, ‘Savings or current?’. More and more Nigerians are opting for digital payments, relying on bank transfers for most transactions. Yet, cash still has its place, especially for trips on public transport and transactions with older people who hold firm to their preference for physical currency.

Older generations have always been skeptical about new technology. Back in the day, some called the television the ‘devil’s box’, and when social media took off, they were quick to amplify its potential harm while downplaying its benefits. Ironically, platforms like WhatsApp eventually became their go-to for pushing their own agendas. It’s no surprise that when ATMs were first introduced in Nigeria in 1989 by the now defunct Societe Generale Bank of Nigeria, they were met with suspicion. Many feared fraud or technical mishaps, and only the well-educated felt comfortable using them. Today, ATMs are as common as corner stores, and nearly every bank customer relies on it for transactions below ₦100,000. In no time, crowds in the bank reduced and queues at ATMs increased. Many people frequently endure extended wait times to access the machine, only to discover that it has run out of cash by the time it’s their turn.

Technological advancements brought new opportunities to meet the growing demands of consumers. The smartphone revolution of the 2000s, along with the rise of app ecosystems, allowed banks to introduce mobile apps that gave people access to banking services anytime, anywhere. Affordable smartphones from brands like Tecno and Itel enabled many Nigerians to join this digital wave. This marked the early days of cashless transactions in the country, as people gradually began adopting bank transfers and using the first generation of banking apps for their transactions.

Despite these technological advancements, only a small fraction of Nigerians initially embraced online banking. Cash transactions continued to dominate; from street hawkers to markets, naira notes flowed freely, the primary fuel for commerce. Commuters were particularly entrenched in this cash-based culture, using physical currency for everything from bus fares to meals and fueling their vehicles. Carrying wads of cash was essential for navigating daily life, and its tangible nature made it difficult for many to trust or switch to newer forms of payment.

Cash payments remained dominant until the rise of Point of Sale (POS) systems, which prompted people to reconsider their reliance on physical currency. For the first time, consumers began to waver in their commitment to cash, as POS machines offered a glimpse into a future where cashless transactions were not only possible but also convenient. Commuters could now pay for fuel without the hassle of carrying cash, and shoppers could buy groceries using the debit cards they had already been using at ATMs. This newfound convenience soon extended to interstate transport, where travelers could swipe their cards at bus parks to purchase tickets. Nevertheless, cash continued to hold a significant place in everyday transactions, often remaining the preferred option for many.

Then came the 2020 lockdown, and for the first time, Nigeria saw widespread reliance on bank transfers. The pandemic forced a shift toward cashless transactions in a way that POS systems had only hinted at. With everyone indoors, people had no choice but to embrace digital payments. In-person interactions, including visits to bank branches, were avoided, and bank transfers became the primary means of sending money to loved ones, paying for online orders, and managing subscriptions. It was a glimpse into a future of full digital reliance, where transactions were seamless and entirely online. Yet, as the lockdown lifted and life resumed, old habits crept back in, and cash started flowing again, especially in markets and on public transport.

Reliance on cash continued until the 2023 Naira shortage, which became the true turning point for many cash-dependent businesses. This time, cash wasn’t just inconvenient; it was scarce. Even those who were adamant about sticking to cash had no choice but to adapt, as finding physical currency became nearly impossible. Banks imposed strict withdrawal limits and POS withdrawal fees skyrocketed, forcing people to pay hefty sums just to access small amounts of cash.The shortage prompted a dramatic shift. Businesses that had previously resisted digital payments began accepting transfers, and even in traditionally cash-heavy sectors like public transport, drivers were seen displaying their account numbers for bank transfers.

As cashless transactions gained traction during the Naira shortage, fintech platforms like Opay, Palmpay, and Moniepoint gained massive traction. These apps made it easy to send money instantly, unlike traditional banks, which often left customers waiting for delayed transaction alerts. The simplicity and speed of these fintech solutions made them an instant hit, especially during a time when every naira counted.

Even before the Naira shortage, ride-hailing services like Uber and Bolt were ahead of the curve, driving the cashless trend. Not only did they enhance the ride experience, making it more affordable and convenient, but they also made digital payment the default. By linking a card to the app, fares were automatically deducted after each trip, seamlessly pushing cashless transactions into the mainstream. While cash remained an option, many commuters preferred bank transfers or direct card payments, further reducing their reliance on physical currency. For most, holding cash was the last thing on their minds when ordering a ride through Uber or other ride-hailing platforms. These services set a precedent for cashless payments, normalising the shift in a way that felt natural and easy for users.

Both the Nigerian government and private companies have played pivotal roles in advancing the push for a cashless future. In 2012, the Central Bank of Nigeria introduced a cashless policy aimed at reducing the circulation of physical cash and promoting electronic payments. Private companies like Touch and Pay (TAP) have furthered this mission by integrating contactless payment solutions into public transport systems.

In Lagos, for example, commuters now use Cowry cards to pay for BRT fares. This system, developed by TAP, has revolutionised public transport. Commuters can easily load their Cowry cards with funds through banking apps or at designated terminals in bus stations. With just a tap on the NFC (Near Field Communication) reader, they can make their fare payments instantly, eliminating the delays and inconveniences often associated with cash transactions. This innovation not only enhances the commuter experience but also supports the broader goal of a cashless economy in Nigeria.

Cashless commuting offers numerous advantages that enhance the travel experience for everyday Nigerians. Take Dotun, for instance, a Lagosian who frequently commutes from Igbo Elerin to Igando. On one occasion, he boarded a danfo, only to realise he had forgotten his wallet at home. The impatient conductor quickly tossed him out, leaving Dotun stranded and embarrassed. Similarly, Chigozie, a newcomer to Lagos, often found himself shortchanged by bus conductors, losing 800 naira in change on one occasion. Cashless commuting could have alleviated the frustrations faced by both Dotun and Chigozie. With a mobile app or card, they could easily pay their fares, eliminating the risk of forgetting cash or being shortchanged.

Despite its numerous benefits, cashless commuting in Nigeria has yet to reach its full potential. Several challenges hinder widespread adoption, including poor internet connectivity, which often delays mobile transactions, and digital illiteracy, particularly among older generations and rural populations. Many Nigerians still prefer cash, viewing it as more straightforward compared to online transfers, which can be fraught with complications such as fake transfers and stamp duties.

Additionally, many drivers solely rely on cash to pay their daily tickets issued by unions. It’s hard to imagine a driver attempting to make a transfer to a National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW) staff member, as such an interaction could easily lead to conflict. For commuters, going cashless can also feel unrealistic for short-distance trips. It would be absurd to board a keke only to disembark and open a banking app to pay 100 naira, especially considering the accompanying transaction fee

For cashless commuting to be fully integrated into Nigeria’s transportation system, improved infrastructure is essential, including widespread adoption of Cowry cards and NFC readers across all public transport. Additionally, developing a robust online ticketing system will facilitate drivers’ payments to unions, making cashless commuting a viable and practical option for both drivers and commuters.

Ultimately, the rise of cashless commuting in Nigeria marks a significant transformation in how people move around. While there are limitations that hinder its full adoption, the convenience of cashless payments is undeniable. As digital literacy and infrastructure improve, more Nigerians will embrace this new way of commuting, leaving behind the era of physical currency. The future of transportation in Nigeria is cashless, and it’s only going to grow from here.