By Babamileko

When two elephants fight, the grass suffers; when two famous influencers fight, brands suffer. In most countries, car prices are a question of engineering, tariffs, currency, and taste. In Nigeria, they can also be a question of virality.

When social activist Martins Vincent Otse, popularly known as VeryDarkMan (VDM), accused businessman Linus Williams Ifejika, also popularly known as B-lord, of inflating prices on imported cars particularly Chinese automobile brand Changan. What looked like an online spat between two personalities quickly turned into a market event.

By the end of the week, prices for some Changan SUVs were under serious scrutiny by Nigerians. What began as a public argument between two people had evolved into an unofficial price war, and more tellingly a referendum on how Nigerians understand the business of importation itself.

The Economics Behind the Drama

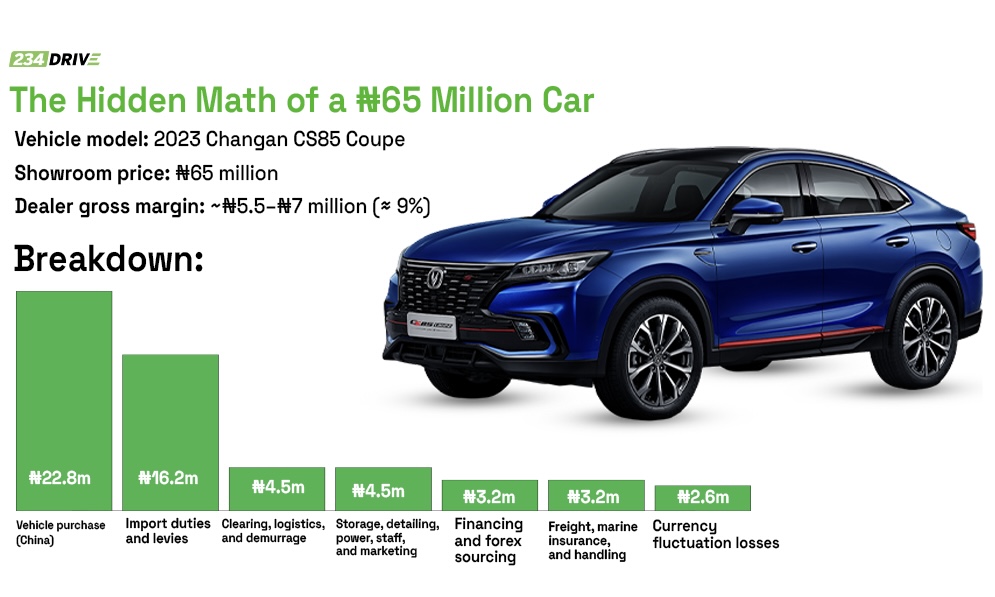

To most Nigerians, a ₦65 million price tag on a mid-size Changan SUV feels arbitrary, even exploitative. VDM’s rhetoric that dealers are simply “adding ridiculous profits” fits easily into a narrative of greed. But the truth, like most things in the import economy, is more complicated.

A single car’s journey from Chongqing to Lagos is a race of volatility. The importer pays in dollars, sometimes at ₦1,500, only for the rate to hit ₦1,700 before the ship even docks. Customs duty alone can absorb 25–35 percent of total cost. Clearing agents, demurrage fees, and terminal rent add several more millions.

Then there’s financing: most importers borrow capital at interest rates of 25–30 percent per annum, with repayment schedules that don’t wait for port delays or border strikes. When you stack all this together, the so-called “profit margin” on that ₦65 million car is rarely more than 8–10 percent.

On paper, that’s about ₦5–6 million profit that can vanish overnight with one policy change, one bad shipment, or, in this case, one viral video accusing you of exploitation.

In his videos, VDM encouraged Nigerians to bypass dealers and import directly—an argument that resonates emotionally but collapses economically.

Individual importation, however empowering it sounds, fragments the market. It means no warranty networks, no standardised safety checks, no after-sales ecosystem. It weakens local assembly efforts and reduces Nigeria to a clearing yard for foreign used cars.

Mikano Motors, the local distributor of Changan in Nigeria, posits that this is exactly what structured dealerships are meant to solve. They shared with us in an official statement:

“At Mikano Motors, we believe that owning a vehicle isn’t just about concluding a transaction; it’s a dependable partnership built on trust, value, and long-term performance. We pioneered the 6-year warranty in Nigeria with the launch of the Changan brand, and with this warranty, our clients enjoy unmatched peace of mind and confidence on the road. Through our strong aftersales network and commitment to service excellence, Mikano Motors continues to deliver not just vehicles, but a complete ownership experience, one that guarantees quality, reliability, and lasting value for every Changan owner in Nigeria.”

Every thriving automotive economy from Morocco to Thailand has built its base on structured importation evolving into local production. When everyone becomes their own importer, nobody invests in infrastructure. As Milton Friedman once reminded us, “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” Every discount demanded in outrage has to be paid for somewhere in quality of service, in safety, or in sustainability.

Why This Fight Matters

At its surface, the feud is entertainmenting, but beneath it lies a profound misunderstanding about how markets function in economies that lack structure. Nigerians are right to question prices but outrage cannot substitute for understanding.

Dealers need to communicate more. Regulators should unify tariffs and modernise customs processes whilst consumers must also recognise that commerce cannot thrive on too good to be true offers and pricing.

VDM’s videos gave voice to frustration. They also revealed how disconnected many Nigerians have become from the mechanics of their own economy: how goods arrive, who bears the risk, and why “markup” is sometimes the only thing keeping supply chains alive.

The real product of this feud is attention. In a hyperconnected Nigeria, attention shapes demand faster than advertising. It can lift a brand or crash a market in 48 hours.

For Changan, one of the fastest-growing auto brands on the continent, the episode is a cautionary tale: visibility can be volatile capital.

A franchise owner spends months navigating customs, forex, and financing only to be side eyed thanks to a tweet. But the inverse is also true: transparency, storytelling, and service can rebuild that trust just as quickly.

The irony is that both sides want the same thing: fairness. VDM wants accountability; dealers want survival. What is missing is the bridge that connects both.

For Nigeria to transition from an import culture to a manufacturing economy, citizens must learn to see margins not as theft but as infrastructure pillars for doing business. Profit, in this context, is what pays for stability, the one thing every importer wishes the naira had.The car market is no exception. Margins, order, and policy are the foundations.

If this feud has shown anything, it’s that economic anger without economic context will always misfire. The next time a viral video demands cheaper cars, the real question should be: how do we build an ecosystem where affordability doesn’t destroy viability?

The VeryDarkMan–Blord saga is a reminder to us that in an age of outrage, knowing how things work is the most radical form of accountability.

The Hidden Math of a ₦65 Million Car

Net takeaway: roughly ₦5–6 million before tax—less than the average Lagos influencer makes in brand deals for a month.

One wrong exchange rate, and the margin evaporates.