On most Nigerian roads today, the view is rather monotonous: rows of Toyota Corollas and Camrys, some Hondas and Lexuses wedged between and the occasional Benz gliding past. Championed for their reliability and maintainability, these cars have become the mainstay of Nigerian mobility. It wasn’t something I ever questioned until recently, when a stroll through the streets of Bordeaux saw me count 12 marques in the space of 1 hour. For obvious reasons, there was a Peugeot majority, but there wasn’t such a wide berth between the following contenders like Mercedes Benz, Toyota, Renault, Citroën and Fiat.

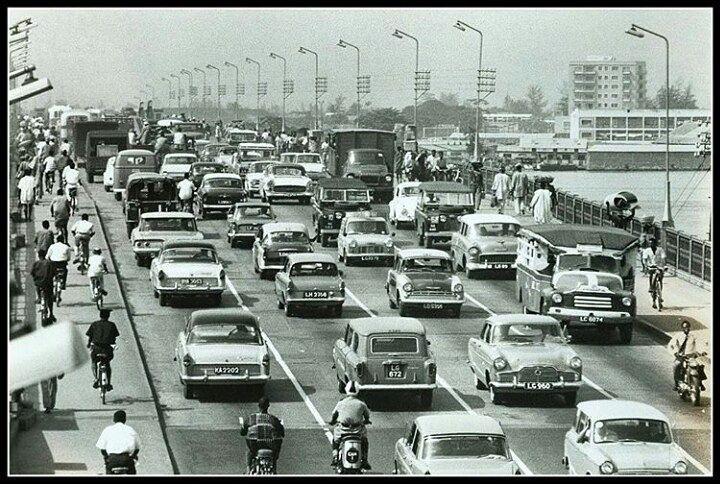

However, I would soon realise that this revelation was also a glimpse of what Nigeria’s automotive landscape once looked like. Decades ago, many of these brands did not have to jostle too much for space on Nigerian roads. They were naturally present, without fuss, displayed in showrooms and newspaper ads, driven by the elite and middle class.

The Faded Brands

In the 1970s and 80s, Nigerian roads were a rolling catalogue of global marques. Renault 12s and 18s cruised beside Fiat 132s, Opel Rekords, Daewoo Racers, and the unmistakable Peugeot 504s. There were also the sturdy Volkswagen Beetles and Passats, which a few Nigerian millennials and Gen Z’s might have inherited as their first cars. Magazines like DRUM ran glossy adverts promising modernity and style, while local dealers filled the newspapers with promotions for the latest imports from Europe and Asia.

Each brand had its own standout offering. Renault’s long-distance appeal was well marketed in the Nigerian press, particularly the Renault 12—once described as ‘the long-distance highway car’. Fiat, the Italian manufacturer, held a steady following through the 1970s. Leventis Motors, with branches in Lagos and throughout Nigeria, stocked and advertised models like the Fiat 127 and Fiat 132 GLS. By the 1980s, though, Fiat’s presence had begun to fade from both Nigerian roads and print. Opel and Vauxhall—then under General Motors—also enjoyed a brief golden era. The Opel Rekord and Omega were popular with professionals and civil servants, while the Vauxhall Magnum was even described as “the craze” in a 1975 DRUM issue. Today, both names have all but disappeared.

Perhaps the most ambitious of the now-absent marques was Daewoo, which had its own outfit in Lagos, Daewoo Motor Services Limited. Incorporated in 1991, the company was a joint venture between South Korea’s Daewoo Corporation (51%) and Nigerian shareholders (49%). By 1992, Daewoo had built a ₦60 million (equivalent to over ₦6 billion today) complex, Daewoo Autoland, which displayed models like the Racer, Espero, Tico, Prince, Korando, Damas mini-bus, and Labo pickup. The Racer, in particular, became a hit. But by the early 2000s, Daewoo cars had vanished, leaving only the company’s name attached to trucks.

Peugeot, once the pride of Nigerian middle-class mobility, managed to linger longer than most. In the 1980s and 90s, Peugeot Automobile Nigeria (PAN) in Kaduna rolled out cars that became part of the national fabric: the 404, the 504, and later the 505 and 406. As of 1990, Peugeot still held the highest number of registered vehicles in the country, largely owing to its domestic production advantage. Today, it still operates, but on a fraction of its former scale.

When Nigeria Built Its Own Cars

On 6th October, 1969—in the twilight of the brutal Nigeria-Biafra war—the then military Head of State General Yakubu Gowon called on 16 automakers to establish assembly plants in Nigeria. And by the 70s, only six of those plants were selected for a government partnership. By 1993, it was reported that there were at least 8 assembly plants in the country, including: PAN in Kaduna; Volkswagen of Nigeria (VWON) in Lagos; Anambra Motor Manufacturing Company (ANAMMCO) in Enugu; Steyr Nigeria in Bauchi, Leyland in Ibadan; General Motors (GM) Nigeria in Lagos and the Truck Manufacturing Company (now National Truck Manufacturers Limited) in Kano.

The companies embodied the government’s vision to transform Nigeria into a self-sufficient industrial nation, fuelled by the oil-rich optimism of the 70s. The goal wasn’t just to assemble cars locally, but also to locally source most of the parts needed to do so. ANAMMCO, Steyr, Leyland and Truck Manufacturing Company assembled trucks and buses—with Steyr also assembling tractors and motorbikes. GM Nigeria produced light and medium duty trucks and buses, as well as back up auto components. And of course, PAN and VWON assembled the cars that traversed most Nigerian roads.

The government’s vision nearly came to fruition. PAN achieved 45% local content, sourcing tyres, windscreens, batteries and radiators domestically. VWON, incorporated in 1972, was partly owned by the federal government (35%), Lagos State (4%), Nigerian distributors (10%), Volkswagen AG of Germany (40%), and BHF Bank Frankfurt (11%). The Lagos plant churned out Beetles and Passats by the hundreds, and by 1991, it had reached 15% local content sourcing. Meanwhile, ANAMMCO’s buses and trucks became fixtures in government fleets. The plants generated thousands of jobs and fostered an ecosystem of suppliers and workshops.

Why Nigeria Stopped Buildings Its Own Cars

Unfortunately, oil money couldn’t shield the industry from policy shocks. The economic downturn of the early 1980s, worsened by the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) under General Ibrahim Babangida, eroded purchasing power and flooded the market with cheaper imports. Take the Peugeot 504 GR A/C for instance; the car that cost ₦8,000 in 1980 shot up to ₦350,000 by 1993.

Locally assembled cars became luxury items and Japanese and Korean brands, led by Toyota and Kia, seized the opportunity to fill the gap with affordable models that required little government mediation. Worse still, imported used cars—so-called ‘Tokunbos’ and ‘Direct Belgiums’—became the only viable option for many Nigerians. The local plants, starved of foreign exchange and burdened by inconsistent policy, began to die slow deaths.

Peugeot Automobile Nigeria was the jewel of the industry. At its peak, the Kaduna plant rolled out up to 90,000 vehicles annually. The company remained profitable even as the economy faltered, making ₦11.5 million in 1992—equivalent to over a billion naira today. Yet behind those numbers was a steady decline. Imported parts were delayed by foreign exchange restrictions, interest rates soared, and government protection wavered.

In 1993, the managing director of PAN Jacques Manlay, asserted that it would not be possible to have a Nigerian car in the next decade, owing to the government’s failure to create a conducive environment for the industry’s growth. For example, in the previous year, VWON reportedly closed their production plants because the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN’s) new policy had forced their Completely Knocked Down (CKD) components to be held up in Hamburg, Germany.

The state had hoped that local content would reach 65% within fifteen years, but it never did. The plants were too dependent on foreign suppliers, and each policy shift further eroded investor confidence. By the early 2000s, PAN’s Kaduna plant was almost dormant.

As for VWON, the company had accumulated a crippling ₦70 million debt, on which it paid 36% interest, by 1992. The inability to retrieve their CKD kits from Hamburg was only the final nail in the coffin. In 1994, the last of the German employees left Nigeria for good. ANAMMCO, which had once supplied over 800 vehicles to governments nationwide, ceased regular production. Steyr and Leyland became largely inactive. The grand vision of local manufacturing had collapsed under the weight of mismanagement and inconsistent policy.

The Push for Revival

By the 2010s, the government attempted to revive the vision. A new automotive policy offered zero duty on CKD kits, 5% on semi-knocked down ones, and a combined 70% duty and levy on fully built cars. The aim was to protect local assembly. The government also revived the Nigerian Automotive Manufacturers Association (NAMA), bringing together legacy plants like PAN, VWON (now VON Nigeria)—which had previously received a ₦1.5 billion federal government injection in 1996 to stay afloat—and ANAMMCO, alongside new players such as Innoson Vehicle Manufacturing (IVM) and Nord Automobiles.

VON achieved 30% local content assembling Ashok Leyland buses for Lagos’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, while PAN resumed small-scale assembly in Kaduna, backed by business magnate Dangote. Innoson, founded in 2010 in Nnewi by Innocent Chukwuma, became the standout success story—producing cars, buses, and SUVs from a laudable proportion of locally fabricated components. The company exports vehicles across West Africa and supplies government fleets at home. Similarly, Nord Automobiles, a Nigerian start-up launched by Oluwatobi Ajayi, focuses on accessible assembly and customisation using mostly local labour and parts. These companies show that some of the old spirit of industrial ambition still flickers.

However, structural challenges remain. Inconsistent policy enforcement, unreliable power, limited financing, and dependence on imported parts continue to stunt growth. The road to revival is littered with past failures, and newer entrants must navigate the same terrain that defeated their predecessors.

The Road Almost Treaded

Nigeria’s automotive story could have followed a different path. With steady policy, its 1970s-era assembly plants might have matured into full manufacturing ecosystems, similar to South Africa or Morocco. Instead, political inconsistency, corruption, and underinvestment turned ambition into decay. PAN and VON still assemble limited units, while Innoson and Nord keep the dream alive, albeit on a smaller scale. The capacity remains; what’s missing is sustained policy, power infrastructure, and long-term investment.

If Nigeria hopes to reclaim its automotive industry, it must treat it as more than a prestige project. It needs consistent governance, incentives for parts manufacturing, and a market that favours local production over imports. Until then, its roads will remain filled with dependable but imported machines—a moving reminder of the innovation that once thrived, and the road that might have been.