The clash between Oluwatobi Ajayi and Stanbic IBTC didn’t trend because it was dramatic, but because it exposed something bigger: the Nigerian financial system’s shaky belief in the country’s manufacturing ambitions.

Ajayi says a customer walked into Nord ready to buy two Nord Max pickups. The financing should’ve been routine. Instead, Stanbic IBTC allegedly told the buyer they don’t finance made-in-Nigeria vehicles and pushed them toward foreign alternatives. According to Ajayi’s posts on X on 11th November, 2025, this wasn’t just a rejection—it was a pattern he considers economic sabotage, especially when some of the same foreign brands classify themselves as “locally assembled” for procurement perks. His public thread, which has since circulated widely, argues that this behaviour contradicts the push for industrial growth under Nigeria’s economic agenda.

This issue didn’t come out of nowhere. Ajayi referenced a long-standing dispute with the bank over a 2022 letter of credit. Nord paid for vehicles at the agreed exchange rate of N430–N480 per dollar, but during naira devaluation, Stanbic IBTC allegedly demanded repayment at over N1,600 per dollar, claiming they never received the forex from the Central Bank. Nord challenged the claim, but the bank later debited N700 million from Nord’s account without notice. The company is now in court, and Ajayi says the experience shaped Nord’s current distance from the bank.

Stanbic IBTC hasn’t commented on the financing allegation. Its head of marketing, Bridget Oyefeso-Odusami, cited the active court case as the reason they can’t speak publicly. But no official statement has addressed whether the bank has a policy against financing Nigerian-assembled vehicles. Industry insiders suggest banks often prefer imported vehicles because they’re easier to resell, seen as lower risk, and already tied to established dealership networks. When interest rates are high and incomes are low, banks tend to choose collateral that moves fast.

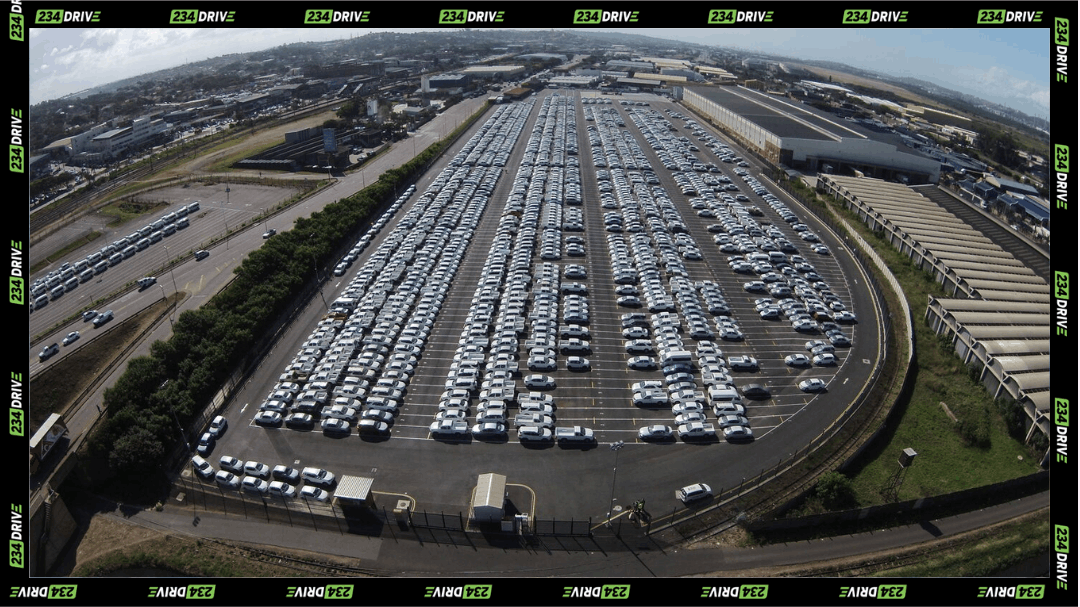

This is where the bigger argument starts. Nigeria’s market still depends heavily on imports despite years of policy reform. Used vehicles dominate because they’re cheap and accessible. Local assembly remains under 10,000 units a year, compared to more than a million imports. Even with used imports dropping sharply in 2024, the “Tokunbo” economy is still the backbone for most buyers. The concern is that if financing institutions discourage local brands, the gap widens, and industrial goals stay stuck on paper.

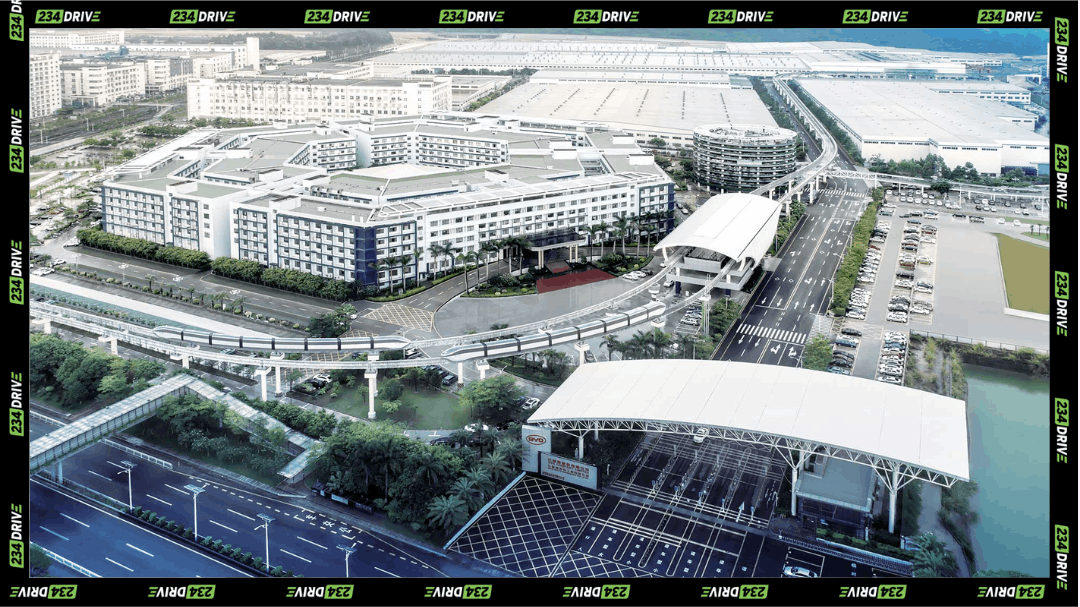

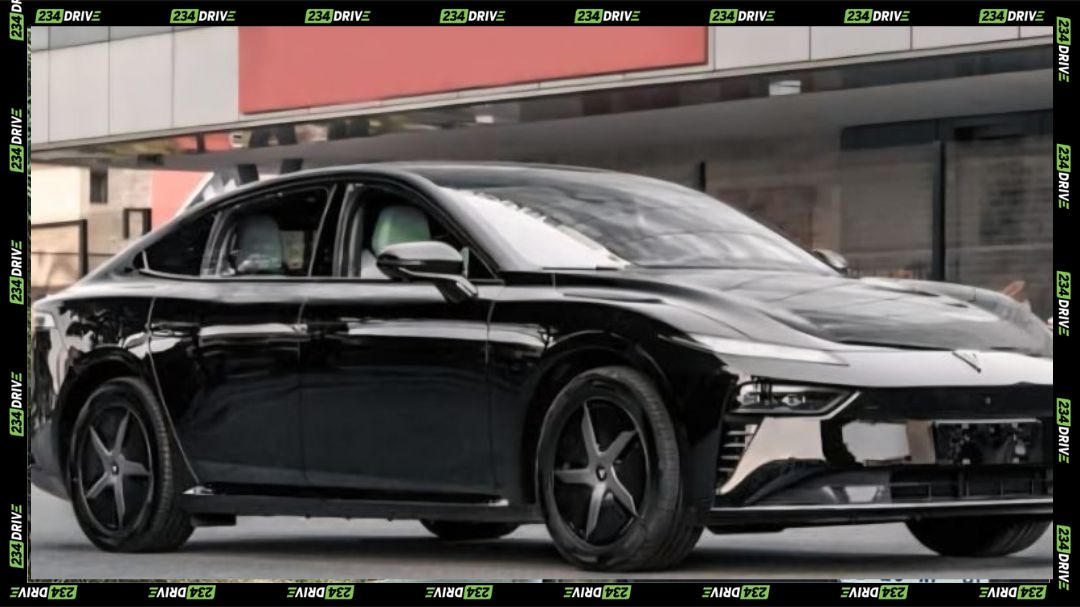

The timing of this controversy makes it even more important. Nigeria is trying to build momentum for EV adoption. The Senate recently pushed the Electric Vehicle Transition Bill forward, and incentives for EV imports and local assembly are still active. Nord has taken advantage of this with its new Tavet Motion EV brand, launching the Luto, Garent, and Vant models. These vehicles are built in Nigeria and priced between N16–32 million, targeting commuters and logistics operators. Nord also builds electric tricycles, a category that could grow quickly with the right incentives.

If financing roadblocks continue, these EV plans slow down. Local manufacturers depend on structured credit and bank partnerships. Without them, adoption becomes a luxury item instead of a practical switch.

Beyond the debate about bank bias, this raises a policy question: should Nigeria push a more aggressive approach to protect and scale local auto manufacturing? Or should financing decisions remain entirely market-driven? Ajayi’s accusations have pulled this tension into public view, and reactions online are split. Some argue for CBN intervention and a review of how banks treat indigenous manufacturers. Others say the public should wait for Stanbic’s full explanation, warning against assuming intent without evidence.

This isn’t the first time industry players have asked for clearer rules. The Nigeria Automotive Industry Development Plan calls for stronger local content enforcement, and the RMI e-mobility report sees Nigeria’s EV opportunity as an industrial catalyst. But without coherent support systems, including financing, the road to ramping up production or reaching projections like 4 million units annually by 2050 stays out of reach.

There’s no clean ending here. The court case continues. The financing debate continues. The EV transition continues. But this episode forces a bigger conversation on whether Nigeria’s institutions are aligned with the vision of building a competitive automotive sector—or whether local players will keep competing uphill.