A heavy downpour on Tuesday 23rd September paralysed movement across Lagos, submerging estates, and neighbourhoods stretching from Lekki to Ikorodu. The rain, which began around noon and lasted for hours, left motorists stranded, and residents confined indoors.

In Lekki, floodwaters spread through popular estates like the Ocean Bay Estate, Victoria Crest III, and the frontage of Buena Vista Estate, forcing commuters to walk through deep water. Motorists crept forward to avoid breakdowns, and delivery riders looking to brave through the water had to push their bikes against the current.

At Ago Palace Way in Okota, gridlock intensified as vehicles struggled through submerged roads. Similar conditions were seen in Akowonjo, Egbeda-Idimu, and Ikorodu, where stalled vehicles worsened congestion.

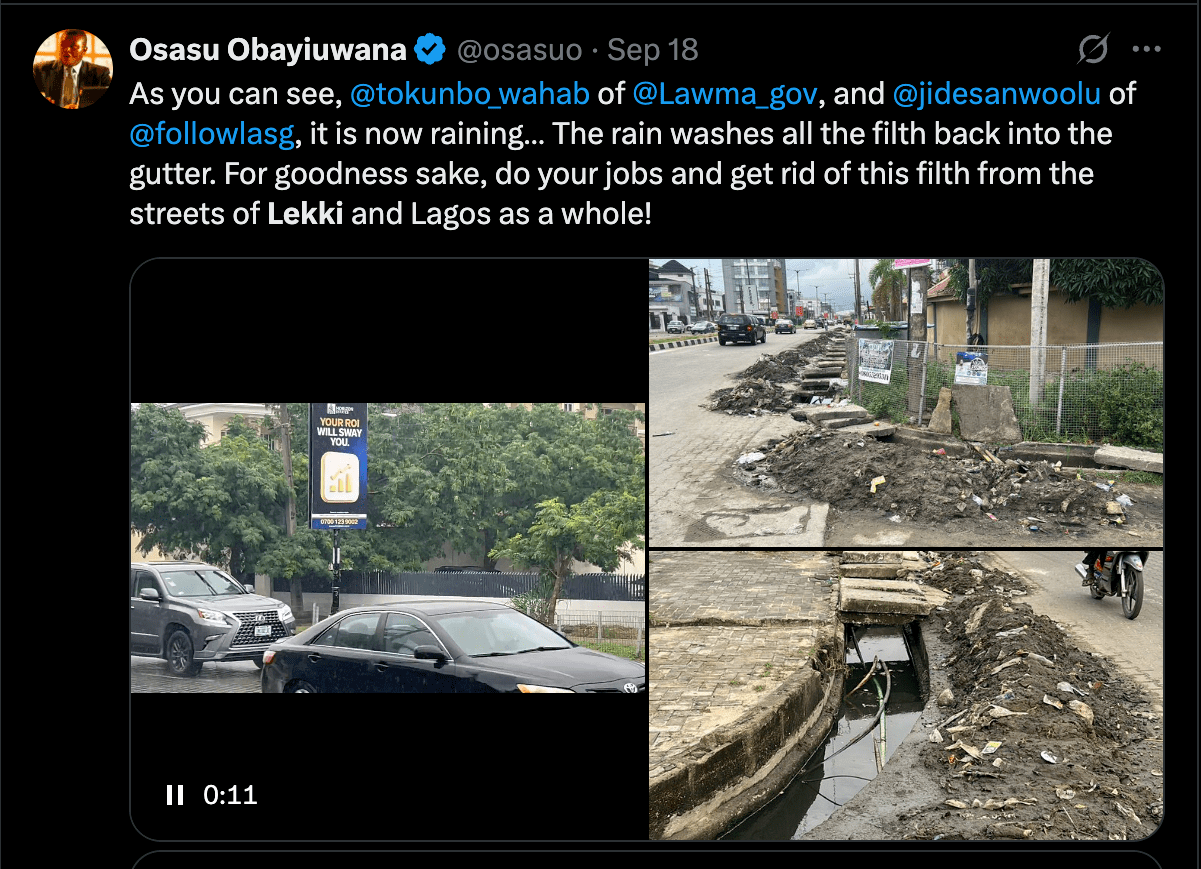

Cleared drainage left piles of dirt on Lekki streets, but the rain has now washed the debris back into the gutters, worsening the flood risk | Source: X (Formerly Twitter)

Traders scrambled to protect their goods as floodwater rose beneath makeshift stalls. A few residents pointed to blocked or incomplete drainage channels as some of the main causes of water gathering around estates. Others pointed out that abandoned road repairs left slopes vulnerable, allowing rainwater to accumulate.

Flood warnings had been issued weeks earlier. On August 4, Environment Commissioner Tokunboh Wahab acknowledged that Lagos’ drainage systems can be overwhelmed by intense rainfall. He explained that the city’s coastal geography makes it prone to tidal lock-ups when lagoon levels rise.

For many residents, these alerts feel ineffective. Commuters in Ogba and Lekki described hours lost in traffic as vehicles stalled at flooded junctions. In Ikorodu, homes and shops sustained heavy damage, with property worth millions affected.

As heavier rains approach, residents argue that annual-advisories alerts are not enough. They are calling for better handling of both existing and future drainage systems, along with a long-term flood management put in place to reduce the impact of Lagos flooding, which routinely turns roads into rivers after every storm.

The challenge is not unique to Lagos or Nigeria alone, countries like Niger and Chad (which recorded over a million people affected by flooding in 2024) have also faced devastating losses.

Nevertheless, other countries with frequent flash floods have found ways to limit the damage. In the UAE, where drainage systems are minimal, rare heavy rains quickly overwhelm roads.

Their solution is practical: suction trucks are dispatched to remove water and keep the city moving. Bordeaux, France, uses a similar system during severe downpours. Saudi Arabia tackles the challenge differently, relying on flood channels and diversion works to reduce the long-term impact of seasonal rains.

For Lagos, the direction should be clear—prevention through better infrastructure must be matched with quick-response aftercare. By combining stronger planning with efficient water removal strategies, the city can avoid being paralysed each time floods occur.