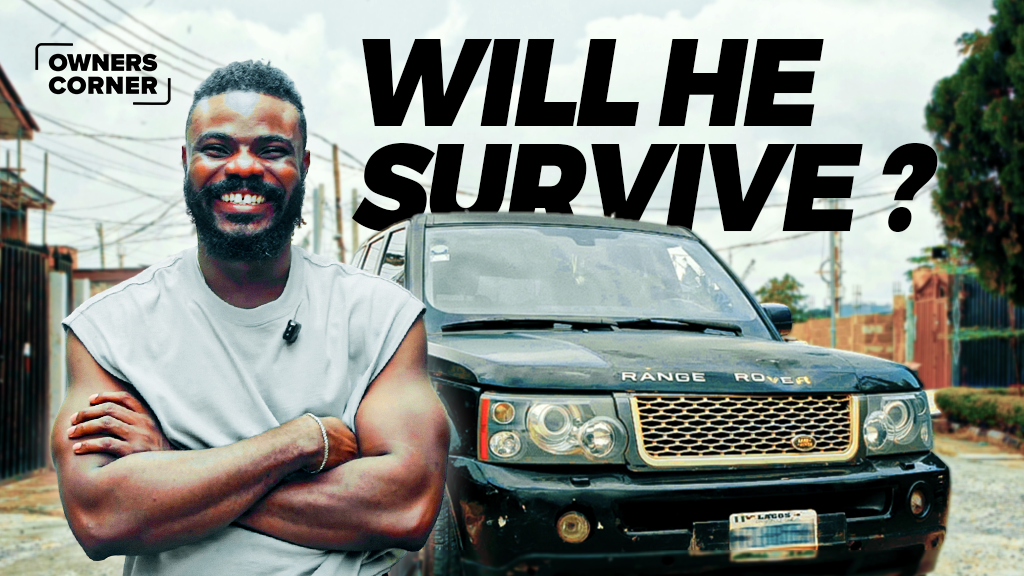

There’s a running joke on X (fka Twitter) about how owning a Range Rover is like inviting a mechanic to join your family. For Afolabi ‘Folastag’ Fasanmi, that’s a lived reality. His mechanic has invited him to his wedding and even asked him to be on the ‘High Table’, a telltale sign of how much business Folastag and his Range Rover have brought the mechanic’s way.

Three years ago, the Lagos-based photographer and chef, bought a 2009 Range Rover as his first car—not because it was sensible, but because it made sense to him. He needed space for camera rigs and catering equipment. He wanted a car that announced itself. And, like many Nigerians navigating a class-conscious society, he understood that how you arrive often determines how you are received. He had considered the Lexus, Toyota RAV4 and even a BMW X6 but the Range Rover called out to him the most.

What he didn’t anticipate was that the car would also become a crash course in mechanical literacy, financial discipline, and emotional endurance. There are easier ways to learn about cars. Folastag chose the hard one.

Welcome to the first episode of Owner’s Corner, 234Drive’s new series exploring what it really means to live with a car in Nigeria.

Why a Range Rover, of All Cars?

From the outside, the Range Rover performs exactly as advertised. It is fast, imposing, and stable on Nigerian roads that seem designed to punish smaller vehicles. It glides through floods, absorbs potholes, and still carries the visual authority that turns heads at events. The engine, Folastag says, has never been the problem. The problems abound elsewhere, in the components that surround it, and the ecosystem that services them.

Within the first three months of ownership, he spent nearly ₦3 million fixing issues he didn’t even know existed when he bought the car. Steering rack. Steering pump. Suspension. Electrical faults. Each visit to the mechanic felt small— ₦20,000 here, ₦50,000 there —until the totals quietly stacked into hundreds of thousands. “You think you’re done,” he says, “then they tell you one more thing remains.”

Frequent suspension issues were a natural result of bad Lagos roads. The original air suspension failed repeatedly. Eventually, Fola converted to manual absorbers—not out of preference, but survival. “Look at my street,” he says, pointing out speed bumps and broken asphalt. “Why won’t I have suspension problems?”

Flooding, at least, isn’t an issue. When Lagos floods, the Range Rover drives. Others swim.

Interestingly, a lot of the damage has come from working with a litany of bad mechanics—bad not because they are clueless about cars as a whole, but because they are often dishonest about how well they can really handle a Range Rover. At some point, Folastag stopped asking “can you fix a Range Rover?” to of course be met with false yeses, and started looking for specialised mechanics who had been tried and tested. But before he learnt to do this, a faulty electrical repair left the car completely dead in Lekki during a multi-day shoot, forcing a tow and weeks of rewiring that required replacing the car’s “brain.” Experience, they say, is the best teacher.

Yet, paradoxically, this chaos is what made him stay. Call it a classic case of Auto Stockholm Syndrome. Folastag and his Range have been through thick and thin, very high highs and very low lows. He will ride it out with her until the wheels fall off—or at least, until he’s in a comfortable place financially to go after the latest trouble-free models.

Over time, Folastag learned the language of his car. He can now tell when something is about to fail by sound, feel, or resistance. He knows which fuel stations to avoid after bad petrol destroyed his fuel pump and stranded him at the Shagamu interchange late at night. He knows which mechanics to trust.

Ownership, in this sense, became participatory. The Range Rover didn’t just transport him; it forced him to pay attention.

The Range Has Taken, But It’s Also Given

There have been humiliations along the way. Topping up steering oil in a suit after a presentation. Missing parts of a wedding because the car broke down outside the venue. Driving home with smoking tires after unknowingly driving with the handbrake engaged for months. Accidents that left body panels missing, rims destroyed, and stories layered onto the car’s battered exterior. And perhaps the most frustrating one, leaving Ojude Oba festival only to have his car stop at Sagamu Interchange, a long way from home. He had to call on people to help push his car in neutral until they found a tow-truck.

Still, Folastag doesn’t regret it.

The Range Rover gave him something he finds valuable: control. Not over the car—that illusion vanished early—but over knowledge. Today, he says he could buy another car without a mechanic present. He understands systems, dependencies, and warning signs. He understands the cost of prestige, not just financially, but mentally.

And prestige still matters. People still step out to look when he says he’s arrived in a Range Rover. Clients still read meaning into the vehicle before they read him. In a country where infrastructure fails but symbolism persists, the car continues to do cultural work even when it’s mechanically exhausted.

Would he recommend buying an old Range Rover in Nigeria? Only with conditions: a solid mechanic, a trusted auto electrician, and an emergency fund you’re willing to burn. Not because the car is evil, but because it demands commitment.

“This car is character development,” he says, laughing. “If you’re not ready, don’t do it.”

And that might just be the most honest review of all. Catch the full story here.