Nigeria is making a huge automatic pivot from being a primary destination for used internal combustion engines (ICEs) to becoming the continental engine room for the electric vehicle revolution. This transition was formally crystallised on 30 January 2026 through a landmark Memorandum of Understanding signed between the Federal Government and South Korea’s Asia Economic Development Committee. This agreement represents more than just a bilateral deal; it is a multi-billion naira industrial statement of intent aimed at establishing the continent’s first dedicated, full-scale electric vehicle manufacturing plant and a comprehensive nationwide charging network. By targeting an annual production capacity of 300,000 vehicles and the creation of approximately 10,000 jobs, the West African giant is positioning itself to lead Africa in the regional green industrialisation race.

The core of this ambitious programme involves a partnership between the Federal Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment, represented by Senator John Enoh, and the AEDC, led by Chairman Yoon Suk-hun. The initiative is structured around a phased development model designed to ensure sustainable growth and genuine technology transfer. In the initial phase, the facility will focus on the assembly of electric vehicles using imported semi-knocked-down kits, allowing the local workforce to familiarise themselves with the intricacies of electric drivetrains and battery management. This commitment is mirrored in the government’s recent policy of adopting locally-made vehicles to lead by example, encouraging domestic consumption before scaling to the wider mass market.

BeyondThis initiative is not merely about building cars,; this initiativeit is about constructing an entire ecosystem that addresses the transport sector’s massive carbon footprint while solving the country’s chronic dependence on imported used vehicles. Currently, used cars account for between 74% and 90% of Nigeria’s annual vehicle imports, a statistic that the government hopes to reverse by providing affordable, locally produced alternatives. The project is tightly integrated with Nigeria’s National Energy Transition Plan and builds upon the growing electric bus momentum observed across several states. By focusing on both the vehicles and the infrastructure—specifically 10,000 charging points across the federation—the project seeks to eliminate the “range anxiety” that has historically hindered electric vehicle adoption in emerging markets.

The division of labour within this partnership is clearly defined to maximise efficiency and expertise. The Asia Economic Development Committee serves as the primary technical and investment partner, bringing South Korean industrial precision and renewable energy expertise to the table. Conversely, the Nigerian government, through the National Automotive Design and Development Council led by Otunba Oluwemimo Joseph Osanipin, provides the regulatory framework, site coordination, and policy incentives necessary to protect the burgeoning industry. This collaborative structure ensures that while the technology is global, the economic benefits and skills development remain firmly rooted in Nigerian soil.

Strategically, this move signals a decisive departure from experimental pilot schemes toward industrial-scale deployment. While previous efforts focused on small fleets, recent successes such as state-led electric buses in Abia and various private EV launches have proven that the market is ready for a more structured approach. By securing a local supply of electric vehicles, Nigeria aims to launch Africa’s first factory of this scale to insulate its economy from the volatility of global oil prices. Furthermore, the focus on battery manufacturing positions Nigeria to eventually tap into the global supply chain for lithium-ion technology, provided the country can effectively leverage its mineral resources and newly acquired technical capacity.

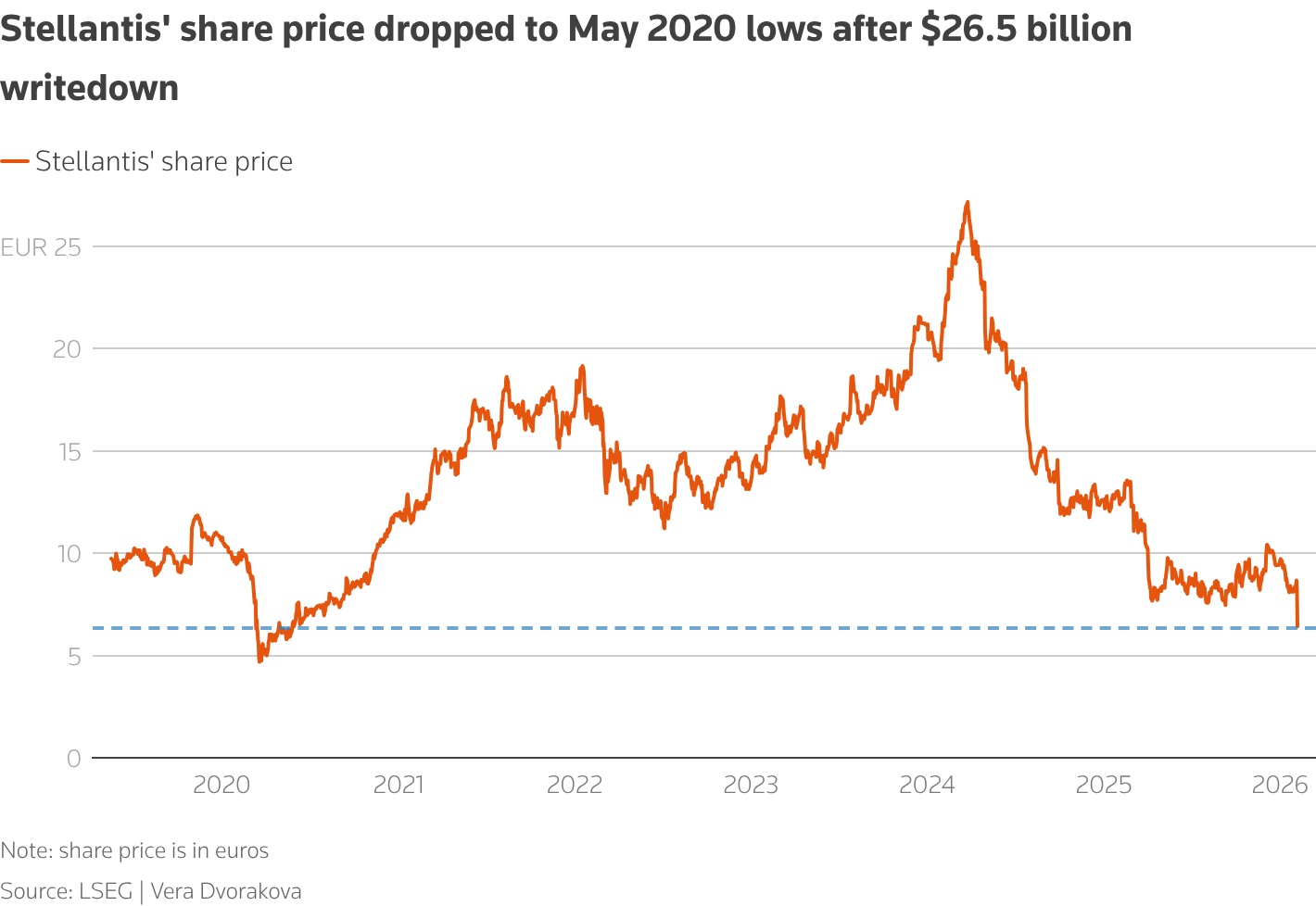

When viewed through a global lens, Nigeria’s entry into full-scale manufacturing is a bold attempt to leapfrog its regional competitors. While Morocco has successfully established itself as a hub for hybrid components and battery gigafactories through deals with Renault and Stellantis, and South Africa continues to refine its legacy assembly lines for BMW, Nigeria’s project is uniquely dedicated to being the first EV factory of its kind from its inception. Unlike Kenya’s focus on electric motorcycles or Ethiopia’s import-heavy adoption model, Nigeria is betting on a vertically integrated manufacturing sector to serve its population of over 200 million people, potentially creating a West African export hub.

The execution details of this deal suggest a rapid move from policy to production. Drawing on the Asia Economic Development Committee’s track record of solar and industrial technology transfers in Asia and Africa, the partnership aims to fast-track the certification and deployment processes. Lessons from other regions suggest that the transition from a signed agreement to a functioning assembly line can take between 18 and 24 months, provided the logistical and power requirements are met. The technology stack will likely involve modular battery designs and software-integrated charging systems that can be adapted to the specific demands of the Nigerian climate and road conditions.

Success, however, is not guaranteed and will depend heavily on addressing the country’s fundamental infrastructure gaps. Critics and stakeholders frequently point to the national grid’s current output of roughly 4,000 MW as a significant bottleneck for a nation hoping to charge hundreds of thousands of vehicles. While the MoU includes provisions for independent charging infrastructure, the broader success of the electric vehicle transition will require a parallel revolution in renewable energy and grid stability. If these hurdles can be cleared, this agreement will be remembered as the moment Nigeria stopped being a passive consumer of automotive technology and became a proactive architect of its own industrial future.

This marks a definitive shift from speculative hype to fleet-scale industrial operations, but it raises a critical question for the years ahead. As the continent’s largest economy prepares to plug in, should the government treat electric charging infrastructure as a public utility—similar to roads and bridges—to ensure that the benefits of green mobility are accessible to all citizens, rather than just an affluent minority?