Every year, the National Youth Services Corps (NYSC) reportedly deploys 350,000 youths to serve their nation. Billions are pumped into the scheme which was devised as a unifying tool for a nation ridden by the after-effects of war but now serves as a solution to unemployment—at least according to the government. Corpers wear the colour combination of green, white—with the added touch of orange. In a way it’s like wearing your country’s colour on you. But the questions that usually follow are whether this attire inspires patriotic servitude or the dread of taking part in a dystopian version of a survival quest.

Among other institutions that strive to disprove stereotypes and unite over 300 ethnic groups in Nigeria, the 52-year-old government scheme has stayed at the forefront and stood the test of time and changing administrations. But why was the scheme necessary in the first place? On what basis must every graduate subject a year of their lives giving to their nation? And what really happens in between those 365 days?

In the Beginning, Dis-unity

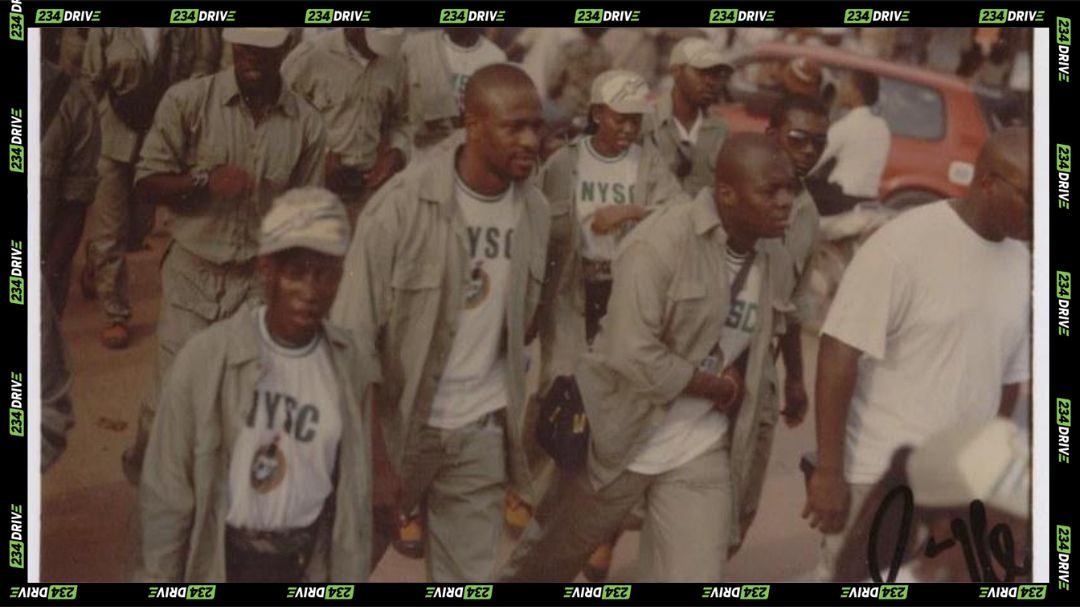

To many Nigerians, the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) is a familiar rite of passage—one year of mandatory service after tertiary education, involving khaki uniforms, orientation camps, relocation, and community development. It is a national tradition that has lasted so long, its significance has become largely subjective. Its origin and history, however, spanned close to a decade and involved diverse players.

The scheme was introduced in 1973, just three years after the Nigerian Civil War ended—a conflict that had nearly ripped the nation apart. But its story starts in 1965 with students from the University of Ibadan. They had proposed a Youth Volunteer Corps that would send young Nigerians to serve in regions outside their own. The goal of this Corps was to mend the cracks left by colonial rule—what many called “the mistake of 1914.”

Nothing happened immediately, but by 1969, with the country deep in conflict, university chancellors once again echoed and pushed for the idea. The military government finally responded in 1973, with the urgency of a country trying to reimagine itself. The war may have ended on paper in 1970, but the divides—ethnic, social, and regional—remained raw. The dreams of students from one corner of the country was now reimagined on a national scale.

So, with a decree on 22nd May, 1973, the National Youth Service Corps was born—designed to send graduates to live, learn, and serve their nation in places outside their home states for one full year.

The scheme’s first Director-General, Col. Ahmadu Ali, was tasked with bringing it to life. And so began the fifty-two-year journey to bind a broken nation together—one batch at a time.

The NYSC Blueprint: Law and Logistics

The NYSC scheme has anchored itself on a three-sided objective through its fifty-two-year lifespan: to promote national unity and integration; accelerate socio-economic development; and finally, to lend an opportunity for participants to glean at increased initiative self-discipline & self-reliance.

Interestingly, the decree, when established in 1973, required governors of each state and the chairmen of the state governing board to provide a minimum subvention of N500,000 for the effective running of the orientation camp. This was in 1973 when N20 could feed a family and the naira went toe-to-toe with the US dollar. The government meant business and so did its figures.

The statutory figure has seen some increase into billions. With the growing population, the figures have simultaneously been hiked to keep up with the rising inflation in the nation.

In the first score of its establishment, the scheme was performing as expected, and arguably even better. The scheme fostered research, eradication of diseases such as bilharziasis and tuberculosis, and a wider spread of education. As of 1988, the Corps had taken in over 296,000 Corps members, with Lagos having the highest quota of 26,000 Corps members.

On January 15th, 1996, Gambia’s Minister of Youth and Sports reportedly tagged Nigeria’s Youth Service scheme as the ‘best organised youth program in the world.’

If you’re currently covered in the dust and sweat of service, this statement may read like something from a folktale. But with a budget of half a million at its inception, how has the scheme maintained its ecosystem down the lanes of time?

A Journey Begins: Tales of Experiences, Economics and Expenses

‘Every year the NYSC deploys 350,000 youths distributed evenly, including in Abuja,’ Angel*, an NYSC staff member, said during a virtual interview on a quiet night in July, ‘we have a robust, organised structure, and we eat three square meals. Even the vendors and ad hoc staff are welcome to the kitchen to eat for free.’

In the 2025 budget, the government allocated close to N33.9 billion for the scheme to run effectively. Out of the figure, N29.54 billion was specifically earmarked for the ‘provision of kits, transportation and feeding for Corps members’. Split 350,000 ways, this is about N84,000 per corper, just a little over the recently updated N77,000 allowance— ‘allawee’—disbursed to corpers monthly. Between 2020 and March 2025, the allawee was fixed at N33,000, so the government likely had to beef up their NYSC allocation to make up for the so-called kit and transportation expenses. The remainder of the NYSC budget was said to cover sitting allowances and an upgrade of various NYSC infrastructure.

The entire twelve months of National Youth Service fit tightly into four cardinal points geared toward unity: mobilisation, orientation program, primary and secondary assignment, and the winding up program.

While N34 billion is the amount borne by the government, the scheme’s participants also take on a lot of the financial burden, even before arriving at the orientation camp.

Mobilising a Nation

‘It’s a blood rush; you can’t register by yourself, so you have to find an accredited cybercafé and they’re not easy to find,’ Hala*, a serving Corps member reminisced, ‘I arrived at one past 7am, and I wasn’t even number one on the list!’

Mobilisation, the first of the four cardinal points, usually begins after graduates have scaled the four walls of a higher institution’s classroom and have their names forwarded to the scheme. And true to its name, it sees a lot of successful tertiary graduates’ scramble to move from one place to another—going from NYSC accredited cybercafés to camp is a world of movements.

It is perhaps the cheapest of the four cardinal points of the NYSC, because the comfort of home is still promised at the end of this exercise.

Foreign graduates on the other hand, usually have to upload the required documents on the NYSC portal. They may also be required to go to the campgrounds to complete their registration prior to the main orientation course, forerunners of the experience to come.

Amongst the bustle and hustle to finish before the portal closes its doors, there is a uniform wonder amongst all applicants as to where their country will take them.

Driven to Serve: The Hidden Cost of Getting to Camp

Green on the traffic light means go and the NYSC green card is no different. This go-sign comes weeks after registration, a beagle blown— start packing up. This card habitually shows up a week before their nation calls and they must answer, with truckloads of money. The NYSC discourages posting Corps members to their state of origin, the state where they studied, or where they currently live. As a result, most are deployed far from home. Only a few are exempt—for reasons of health, security, or marriage. In the case of married Corps members, women are typically posted to the state of residence of their husband.

‘I had to go to camp like every other person. I was posted to Zamfara but because of the insecurity challenge, I was to do my orientation camp at Sokoto. I had to set off from the park in Kaduna by 7am on a bus for a journey that was supposed to last 9 hours. I paid N13,000 at the park and N2000 extra for my load, making it N15,000,’ Itace* shared her eleven-month-old memory of her experience, the exhaustion still hanging in her voice. ‘It was another N5000 to camp,’ she added.

Nowadays, even short interstate trips like Kaduna to Plateau now cost around ₦10,000. Abuja to Yobe runs at ₦16,000, and within the North, travel rarely falls below ₦10,000. Cross-country trips, like Kaduna to Port Harcourt, can exceed ₦50,000.

Despite zonal quotas aiming for balanced deployment, many camps still pull members from distant regions. For instance, in 2025, Yobe received few from the South-South but had more from the South-East and North-Central.

With an estimated 350,000 Corps members mobilised each year and an average transport cost of ₦20,000 per person, Nigerians spend roughly ₦7 billion annually just to reach orientation camps — and that’s before the service year even begins. These figures sway with the tides of fuel price hikes—rising and stumbling as the cost of movement becomes a national guessing game.

To get to a place where national virtue resides, a lot of financial virtue pours out of the prospect Corps members.

An anonymous NYSC staff reports that there’s currently a Memorandum of Understanding with the various transport organisations like the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW) and the Ministry of Aviation, but there was no evidence of these tracks leading to the Orientation Camp amongst interviewed Corps members—perhaps this transaction occurs when the Corps members have to leave to the PPAs from the camp grounds.

On arrival at the states of deployment, Corps members are usually victims of eager transport workers looking to take advantage of the unsuspecting travellers. ‘I spent N2500 to get to the camp in Iseyin from Iwo Road in Ibadan,’ Divine recalled her experience dating nine years back, ‘it even didn’t pain me until much later, when I had grown accustomed to the place, that I was cheated, as per JJC now. I wonder how much it is now, because this was when Kaduna to Ibadan was N5500.’

Many other Corps members, even within the same region, attest to the fact that this is when the money spending spree starts. It is clear: your pockets do not belong to you anymore. The exhausting experience follows with checkpoint packages, necessary ‘stop and search’ and Nigeria’s epileptic road system to stir up everything in them.

Served and Serving: Who Really Eats in NYSC Camp?

Seven years on, Vincent, now a tailor in Northern Nigeria often found a phrase lingering on his lips whenever ‘NYSC’ was mentioned. ‘Whatever happens in orientation camp, is beyond your control,’ he said, with a strained chuckle escaping, ‘whatever happens after camp, is entirely up to you.’

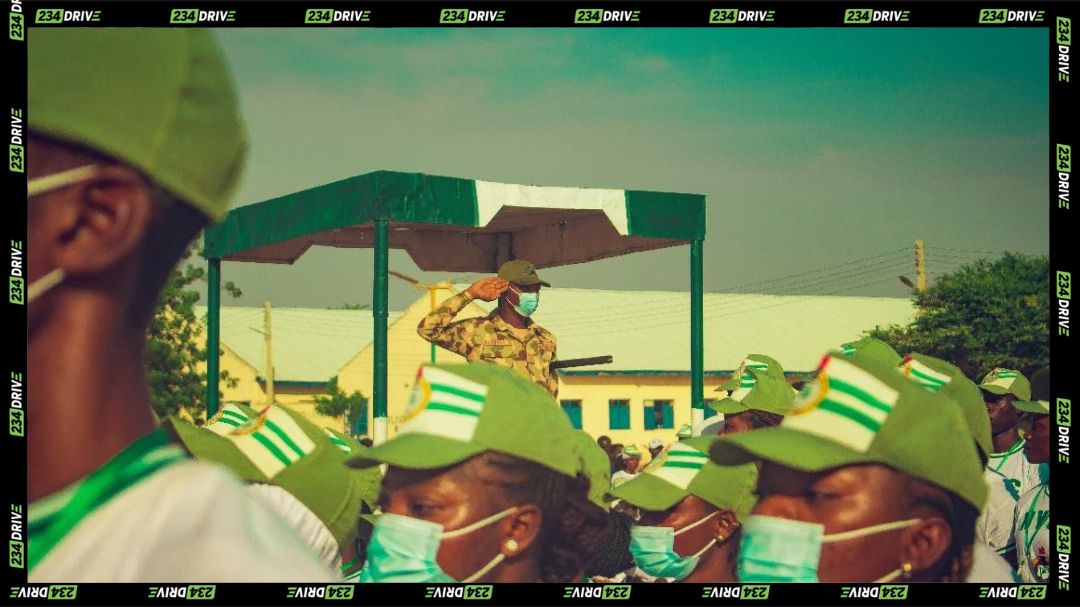

The camp’s four walls mash youths from different parts of the country—the first sign that there’s really not much of a difference between them, or at least not in their new travail. From their rooms to the kitchen, cultural differences are swallowed up in uniformity and uniforms. This exercise recurs six times every year, with each batch taking its own quota of 3 weeks, to shape its members for service and survival.

‘You’re billed from the gate guy! During the early post-covid era, you had to buy facemask at the gate! The ones you bring aren’t ‘good enough’ or up to ‘standard’. Sanitiser alone was like 3k o!’ Buratai*, a solitary freelance UX designer exploded as he drove his mind back to his orientation memory lane in 2021. That would rake figures up to about N3 million alone from sanitizer sales alone from one orientation camp.

And with wallets opening from the gates, so too do the cracks where naira will quietly slip away.

For the corpers who resume with little to no provisions and accessories to save money for transport, expenses catch up with them in the faces of the smiling Mami vendors. An anonymous NYSC staff reports a feverish excitement whenever camp resumes for the vendors.

Everything except oxygen sells at the Mami markets of NYSC orientation campgrounds. And these vendors milk the most out of it because even they paid to be there, from all over the nation.

Befuddled Spenders, Extravagant Vendors

There was a recycled tale in Delores’s family about how terrible camp food is, so she resumed prepared to avoid the free camp food, save for the testimonial Sunday rice to which a battalion of Corps members attest to God’s goodness in the kitchen on Sundays.

My findings revealed that across all camps, the cheapest food on the Mami market food list went only as low as N1000. Abuja Corps members (along with other Camps like Lagos), with their numbers swelling close to 4000 members in its first batch, hold their figures at N1500 for a plate of rice and beef.

This is a price put in place by the camp authorities to avoid their members paying with body parts to eat food because money is exhausted. These price regulations, stretching beyond food, seem strictly observed only in a few camps.

At least N3000 is spent per day on meals. This translates to about N63,000 being passed off on food alone on average per Corps member over the 3-week camp period. Annually, that is an outflow of approximately N22 billion per year on feeding for 350,000 Corps members.

The closest naira denomination to follow in use would be N500, for those who want to charge their gadgets, since there are no charging ports in the hostels. That is another half a million possibly pumped into the Mami phone economy between charging vendors in a single day, supposing every single Corps member charges daily. It is an eventuality almost no Corps member can escape; all gadgets must pay homage to charging hotspots.

Even laundromats want a taste of the endemic money laundering, a field day of monopoly, charging as high as N500 to launder just a single shirt.

All the roads in the camp that don’t lead to the halls, parade ground and hostels, lead to the Mami market.

With a spending of N1,500-N2,000 for the 21 days at camp for the minimalists, about an average of N42,000 helplessly pours out of their pockets. ‘I spent almost N50,000 at camp,’ a minimalist Corps member currently serving from a corner in a radio station reports, ‘and I wasn’t even eating every day at Mami at that. I had provisions o!’

One Size Fits None

Kits are provided at the camp at the conclusion of registration—the scheme boasts of over two garment factories which produce the necessary wares for their 350,000 members.

But what should be good news for corpers is, in reality, a ‘one size fits none’ craze that leaves them stranded at the registration office doors. For distrusting Corps members who couldn’t find kit swaps to fit them, they often find themselves jerked into an abusive financial relationship with eager, itchy tailors who sew their mouths shut with their prices. What ordinarily should be a N200 adjustment quickly balloons into a N2,500 tailoring toll. The threads don’t change in camp, but the prices do.

‘Yeah, there are factories, but it’s not enough for the numbers, so the Corps still hands out contracts to make the kits to some private contractors,’ Kala*, a recent hire in the NYSC’s ranks, said during a virtual interview. Even in 2025, there was a call for contractors made by the NYSC.

Whatever the case, there is a uniform cry from corpers that the quality of the material is horrible and that ‘the Corps can do better, but it won’t.’

Conquered in 21 Days, Bound for 365

After 3 weeks of controlled, compact activities, the members are deployed to their Primary Places of Assignment (PPA) and for their Community Development Service (CDS). The list of postings to local governments is read out to the members by their platoon leaders.

The buses, whose poor conditions are often a foretelling of the place they will spend a year of their lifetime in, are provided by the various Local Governments of the state. The Corps members, doomed or undaunted, march to the next phase of their assignment, or head home for their two week-break to mend the broken pieces of their finances.

Corpers like Hala*, who already lost faith in the system even before the journey began, take their load and take no chances with their finances and to head back home. In her mind, rest precedes service after surviving the paradoxical ordeal where vice meets virtue.

Estimates on the trip back to her father’s house in Kaduna from the campground in Sokoto parred up with the N20,000 it took to arrive there in the first place; a haunting, exhausting figure for a purpose she feels she will question for a long time.

Fading into Routine and Relapse

Over the remaining months, Corps members scramble their time between their Primary Place of Assignments (PPA) and Community Development Service (CDS). The primary assignments are where the Corps members actually serve under an employer. Primary assignments usually shuffle corpers around, from school placements, government agencies, hospitals, NGOs, media houses, to law firms and banks. They span across a wide range of sectors.

These employers are statutorily required to provide housing and transportation services. The pay used to be a combined allowance of ₦350 (₦250 for housing, ₦150 for transport), as set in the original 1973 decree. While that amount once sufficed, it won’t buy a loaf of bread in 2025.

Most PPAs either pay compensatory stipends or offer nothing in addition to the government-disbursed allawee, often citing incapacity. Some outright reject Corps members while others exploit their free labour, offering “experience” in place of support.

CDS, which runs concurrently with the PPA, involves weekly group projects like health outreach, legal aid, or environmental campaigns—that were originally designed to promote civic engagement, though nowadays it has mostly been reduced to routine attendance.

National Service or National Evil?

‘NYSC is not necessary; it is evil that is not necessary,’ a displeased corper serving in southern Nigeria swears. ‘I don’t know what the worst part is, the bad toilets or the dust and lack of water or getting posted to the middle of nowhere where you have to wear your NYSC fit for CDS and everyone starts looking at you and trying to guess your origins, mostly not for good reasons.’

After the declaration of Goodluck Johnathan as the winner of the 2011 General Presidential Elections, the bloodbath that followed claimed the lives of about 10 Corps members in northern Nigeria. Since then, cries for scrapping the scheme have intensified.

What has apparently kept the scheme relevant over the recent years is the requirement of an NYSC certificate by most employers. As far as many are concerned, it has served its purpose and fixed the buildings and minds broken by the war, but it is not what Nigeria needs as a people now.

There have been calls for a review or a total scrap of the scheme, with emphasis on the Corps outliving its use. ‘I don’t see the use of it,’ a young graduate retorted when asked about why he had not gone to serve, ‘what is the use of spending an entire year in a place where there’s no likelihood I will make meaningful change.’

For others, it’s part of the to-do list of being Nigerian. After one is done with school, NYSC is often the bridge for most people to cross before they get a job, before they get married.

* Names have been changed to protect anonymity