While Detroit debates tax credits and tariff walls, China has quietly turned 2025 into the year of the electric vehicle avalanche. Between November 2024 and October 2025, Chinese automakers launched 91 new cars globally accounting for roughly half of all new vehicle introductions worldwide during that period. BYD and Geely didn’t just participate in this surge; they led it, with BYD alone securing approval for 38 new passenger car models in China and Geely rolling out five fresh hybrids in the second half of 2025. Meanwhile, American brands managed somewhere between five and ten major EV launches, a disparity that speaks volumes about development speed, supply chain integration, and the growing chasm in global automotive ambition.

The numbers tell a stark story of industrial momentum. In China, BYD, Geely, and Wuling collectively received regulatory green lights for 83 passenger car models over the twelve-month window, most of them electric or plug-in hybrid vehicles. BYD’s lineup now spans everything from the affordable Dolphin hatchback, priced around £26,000 in some markets, to the high-performance Yangwang U9 supercar that hits 100 km/h in 2.36 seconds. Geely focused heavily on hybrid technology, introducing models like the Galaxy M9 SUV and the Galaxy A7 sedan, while refreshing its Xingyuan compact EVa best-seller that continues to dominate China’s entry-level segment. Globally, Chinese brands pushed out vehicles across all categories: pure EVs, gasoline cars, light trucks, and crossovers, reflecting a product strategy that prioritizes volume, variety, and rapid iteration.

Compare that to the American side of the equation. General Motors brought the Chevrolet Equinox EV and Blazer EV to market, emphasizing affordability with starting prices below $35,000 and ranges exceeding 300 miles. Cadillac expanded its electric luxury portfolio with the Optiq, Vistiq, Escalade IQ, and ultra-premium Celestiq. Dodge launched the Charger Daytona, a muscle car reimagined with electric powertrains, while Lucid introduced its Gravity Grand Touring SUV at a starting price of $96,500. Tesla, the EV pioneer, focused on updates rather than entirely new platforms, refreshing the Model Y which remained the top-seller in the first half of 2025 with 157,000 units and potentially prepping a compact Model Q for budget-conscious buyers. Ford tweaked its F-150 Lightning and Mustang Mach-E, but these were evolutionary steps, not revolutionary leaps. The total? Roughly a dozen significant launches, depending on how generously you count variants and refreshes.

The speed gap is even more revealing than the volume gap. Chinese automakers are bringing new models from concept to showroom in as little as 20 months, half the time it takes legacy Chinese firms and a fraction of the 40-plus months typical for Western manufacturers. This acceleration stems from vertically integrated supply chains, with companies like BYD producing their own batteries, motors, and even semiconductors. Fixed supplier relationships eliminate lengthy negotiations, and control over raw materials, lithium, cobalt, nickel removes bottlenecks that plague competitors. Geely operates under a similar model, with in-house battery production and strategic partnerships that allow rapid prototyping and deployment. In China, the entire ecosystem from regulatory approval to manufacturing capacity is geared toward EV adoption, with government subsidies, infrastructure investment, and emissions standards all aligned to accelerate the transition.

Performance data underscores China’s technical prowess in ways that go beyond spreadsheets and sales figures. Chinese electric vehicles now occupy the top three spots in global 0-100 km/h acceleration rankings for new energy vehicles. The GAC Aion Hyper SSR leads at 1.9 seconds, followed by Xiaomi’s SU7 Ultra at 1.98 seconds and Geely’s Zeker 001 FR at 2.02 seconds. Nine of the top 20 fastest-accelerating EVs are Chinese, including BYD’s Yangwang U9 and Han EV, which clocks in at 2.7 seconds despite being positioned as a luxury sedan rather than a dedicated supercar. Tesla’s Model S Plaid, at 2.1 seconds, remains competitive, but the broader pattern is unmistakable: Chinese manufacturers have mastered dual-motor configurations, high-voltage battery architectures, and lightweight materials at scale. These aren’t concept cars or limited-edition halo models, they’re production vehicles, available for purchase, and increasingly exported to markets in Europe, Southeast Asia, and beyond.

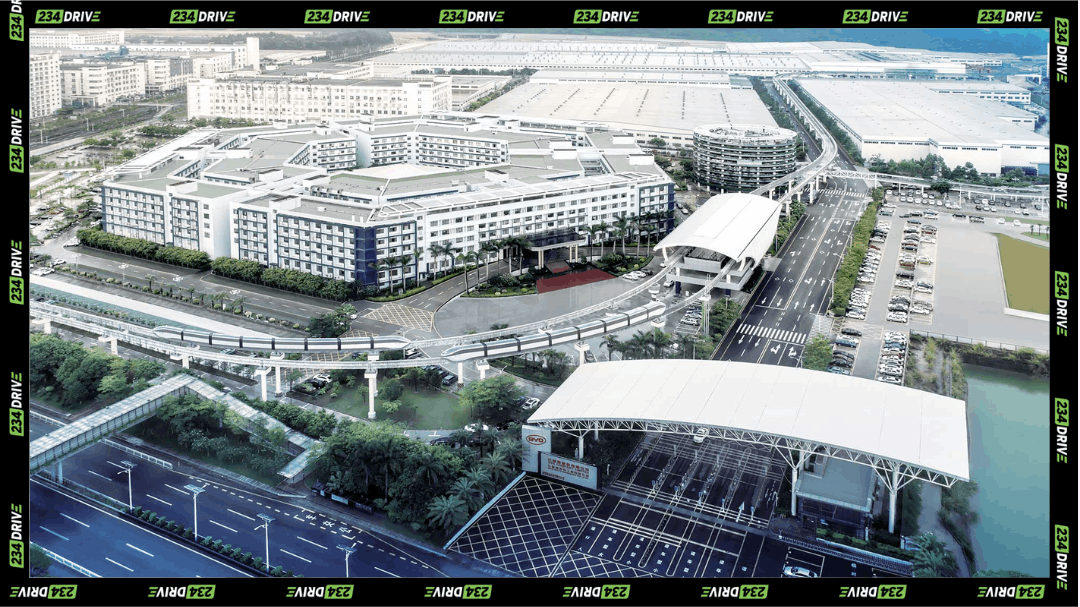

BYD exemplifies this execution velocity. The company’s Seal marketed in some regions as the Song Plus racked up 262,445 sales in the first nine months of 2025, capturing 4.8% of the global plug-in hybrid market. The Qin Plus topped monthly sales charts in June with 25,000 units sold. The Han L EV flagship arrived with LiDAR for autonomous driving and a 2.7-second sprint time, positioning it against premium German sedans at a fraction of the cost. Geely’s strategy mirrors this approach, with the Galaxy M9 plug-in hybrid SUV opening for orders in August and the Xingyuan compact EV setting aggressive sales targets after a midyear refresh. Both companies are leveraging China’s domestic market where EVs now represent 50% of new car sales as a proving ground before scaling internationally. In the first ten months of 2025, China exported 2 million EVs, a 90% surge year-over-year, underscoring how domestic success translates into global market share.

The United States, by contrast, is grappling with a policy environment that prioritizes protectionism over acceleration. Tariffs exceeding 100% on Chinese EVs have shielded domestic manufacturers from direct competition but also insulated them from the innovation pressure that drives rapid iteration. EV-related investment in the US tumbled in 2025 as tax incentives were scrapped and emissions regulations relaxed, leading experts to warn that the country risks ceding not just market share but entire value chainsbattery production, motor technology, software integration to China. EV penetration in the US remains below 10% of new car sales, compared to China’s 50% and Europe’s 20%. Record Q3 2025 sales of 438,487 units in the US were driven largely by last-minute tax credit rushes, not sustained demand.

China’s industrial model isn’t without vulnerabilities. The country hosts 129 EV brands, a crowded field expected to consolidate to fewer than 40 by 2030 as subsidies taper and competition intensifies. Labor costs and environmental standards differ significantly from Western markets, raising questions about long-term sustainability and ethical sourcing. Yet the competitive pressure within China has forced companies to innovate or die, creating a Darwinian ecosystem that rewards efficiency, scale, and customer responsiveness. Western automakers, meanwhile, are optimizing for quarterly earnings and shareholder returns, a fundamentally different calculus.

This marks the shift from EV experimentation to EV dominance, and the question isn’t whether China will lead the global automotive industry, it’s whether the West can find a way to compete without retreating into protectionism. Should the US treat EV supply chains as critical infrastructure, warranting investment on the scale of highway systems or defense tech? Or will tariffs and slow incentives ensure that by 2030, the roads are filled with Chinese badges, regardless of where they’re driven?