Nigeria’s Senate has passed the EV Transition Bill through for its second reading, and that’s the clearest sign yet that Abuja wants road transport to start moving away from petrol and diesel. Unlike the 2019 phase-out attempt, this version is more incremental. It tries to build an entire EV ecosystem-first policy comprising local assembly, charging and incentives before talking about tighter controls on internal combustion engine (ICE) imports. The bill, sponsored by Senator Orji Uzor Kalu, is now with the Senate Committee on Industry for further work, after which it will return for third reading. If it stays in its current shape, it will become the closest thing Nigeria has had to a national EV framework.

At its core, the bill tries to solve three problems at once: emissions, forex drain from fuel, and weak local auto manufacturing. Transport accounts for an estimated 30% emissions, especially in cities like Lagos, Kano, and Port Harcourt where old buses, informal ride operations, and poor traffic flow make tailpipe pollution worse. Cutting that number without crippling mobility means getting cleaner vehicles on the road. At the same time, Nigeria spends heavily on fuel and still battles scarcity. If more urban commuters charge cars at home, at workplaces, or at converted fuel stations, daily reliance on petrol drops. And if the vehicles themselves are assembled in Nigeria, with a growing percentage of local content, you start retaining value locally instead of importing fully built units. That is why the bill links EV promotion to industrial policy.

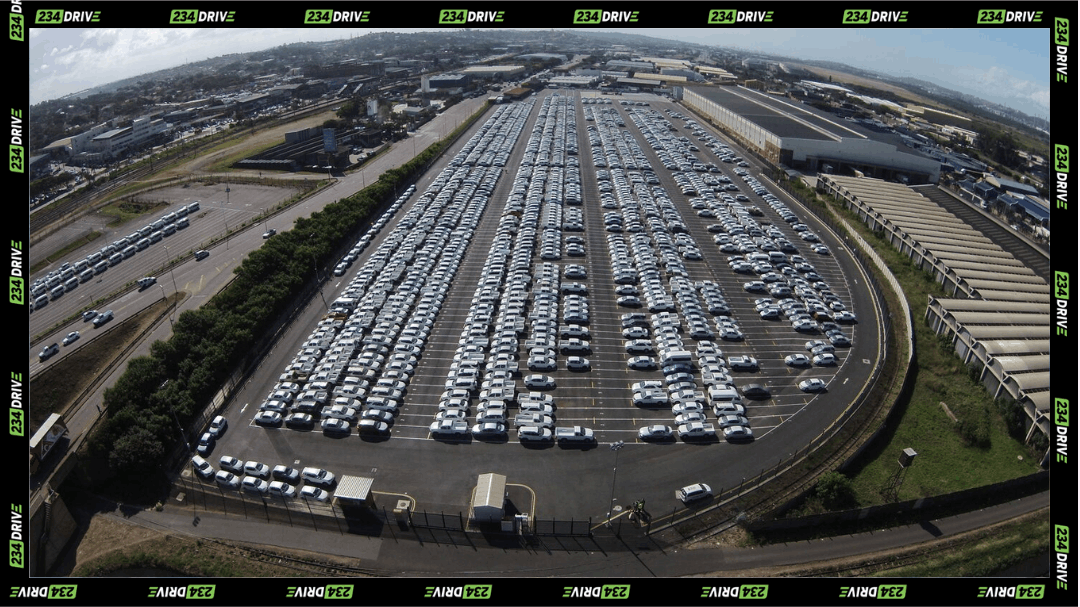

One of the biggest shifts in the text is the insistence on local content. Foreign automakers who want to sell EVs here must partner with licensed local assemblers and are expected to set up domestic assembly within three years of passage, sourcing 30% of components locally by 2030, numbers that align with what several senators described as a “build here, don’t just sell here” approach. This mirrors policy moves in other African markets. Kenya and South Africa often come up in Senate debates as benchmarks so the drafters are clearly trying to prevent Nigeria from becoming a pure end-market while neighbours become manufacturing hubs. Lawmakers like Senator Titus Zam even warned that Nigeria risks falling behind if it does not codify EV policy now.

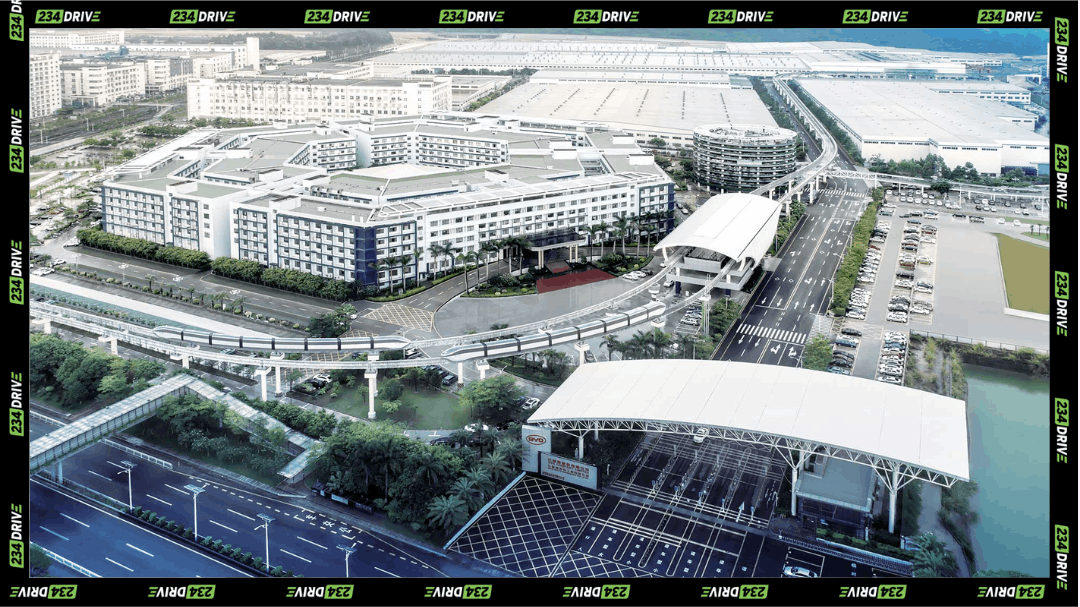

The operational piece is just as important. The bill wants every fuel station to install EV charging points, backed by tax incentives. That’s ambitious for today’s power realities, but it is strategically smart; fuel stations already sit on prime mobility corridors, already have payment flows, and already serve vehicle owners. Turning them into dual-use energy hubs makes more sense than trying to build hundreds of new standalone charging yards from scratch. The bill also proposes a promotion council to coordinate federal, state, and local actions so that someone is actually tracking compliance, licensing assemblers, and publishing standards rather than leaving it to scattered MDAs.

Where the bill gets unusually firm is enforcement. Non-compliance with local content rules can draw fines of up to ₦250 million, while importing unlicensed EVs can attract up to ₦500 million plus confiscation of the vehicles. Local assemblers are also expected to hit a minimum annual output of 5,000 units under recognised safety standards. That’s a strong signal to both genuine manufacturers and opportunistic traders: this won’t be a free-for-all. It also reassures policymakers that the incentives they are putting on the table will translate into real plants, real jobs, and real technology transfer, not just paper companies.

The economic upside is easy to see. A functioning EV policy can create thousands of jobs across assembly, bodywork, battery pack integration, charging installation, software, maintenance, and power solutions. Nigeria sits on lithium reserves; tying that resource base to domestic battery or component production could become a new export narrative if the government follows through. Senators also framed the bill as part of President Bola Tinubu’s broader diversification and clean-energy agenda. Senate President Godswill Akpabio explicitly said so on the floor. Even if full EV penetration takes years, the signalling effect alone can help attract foreign automakers looking for a West African base.

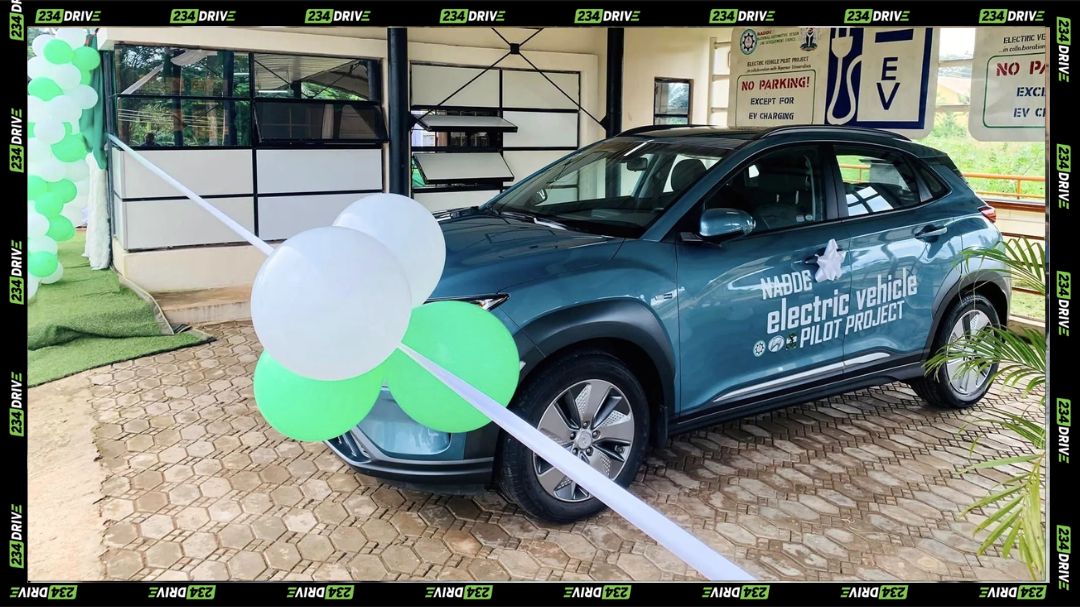

The environmental case is straightforward. The transport sector is a big emitter and a big public-health problem. EVs remove tailpipe emissions from the point of use, so urban air quality improves, especially where danfo buses, ride-hailing fleets, and small delivery bikes concentrate. But this is also where the main critique enters: if most EVs charge from a grid that still runs on gas and diesel, how much net emission reduction do you actually get? Environmental economists call this the “upstream emissions” problem. The bill doesn’t make the grid green on its own, so power-sector reform is non-negotiable if Nigeria wants to claim deep climate gains. That said, several pilot projects, e.g.solar charging hubs, show that distributed renewables can cover at least part of the charging need.

Still, implementation will be messy. Power supply is unreliable. EVs are expensive upfront. Poverty levels are high. Most Nigerians buy used vehicles, often over a decade old, not shiny new EVs. Without subsidies, concessional financing, or a used-EV import pathway, adoption will concentrate in Lagos, Abuja, and maybe Port-Harcourt—basically among middle-class early adopters and corporate fleets trying to cut operating costs as petrol prices rise. That’s why the bill’s gradual timeline matters. Unlike the 2019 proposal which aimed for an aggressive petrol phase-out by 2035 and collapsed under criticism, this one is designed to let infrastructure, financing, and local industry catch up. It is evolution, not an overnight switch.

Policymakers will have to show real pilots converted fuel stations with chargers, Lagos or Abuja government fleets running EVs, local plants producing 5,000 units a year before most Nigerians believe it. Human-interest stories from Lagos drivers already hint at the upside: cheaper daily running costs, quieter rides through traffic, and relief from fuel-queue drama. If those stories multiply, public sentiment will soften.

So where does this leave Nigeria? If the Senate keeps the strong local-content language, funds the promotion council properly, and works with the power sector to ring-fence energy for transport, Nigeria can realistically build an EV foothold in the next five to seven years. If not, the bill risks turning into another lofty climate-and-industrial policy document that lives on paper while the streets stay full of used Tokunbo cars. The bill is a necessary step, it aligns Nigeria with what other emerging markets are doing, and it gives investors clarity. But execution, power, financing, enforcement, and public buy-in will decide whether this becomes a real mobility transition or just another headline.