Uber has cracked the code on electric ride-hailing in emerging markets—not with hours-long charging waits, but with battery swaps that take under 60 seconds.

The ride-hailing giant launched Uber Go Electric in Johannesburg in late November 2025, deploying South Africa’s first fully electric four-wheel ride-hailing service with 70 compact Henrey Minicar EVs already on the road. The fleet will scale to 350 vehicles by late January 2026 through a partnership with local energy startup Valternative Energy, which provides the vehicles on rental terms and operates a revolutionary battery-swap network that lets drivers exchange depleted batteries for fully charged ones in under one minute. The system runs on solar and hybrid backup power, making it resilient to South Africa’s notorious load-shedding blackouts while slashing driver operating costs by 30-40% compared to petrol alternatives. Riders pay standard Uber Go budget prices with no green premium, making zero-emission transport accessible across Johannesburg’s townships and suburbs.

The Henrey Minicar sits at the heart of this operation. A compact Chinese four-seater EV priced under R200,000 that balances affordability with practical urban range. These aren’t luxury vehicles chasing premium riders; they’re purpose-built workhorses designed for high-mileage gig economy deployment in congested city centres and underserved neighbourhoods. The compact footprint suits Johannesburg’s traffic patterns perfectly, slotting between motorbikes and traditional sedans for quick passenger pickups and efficient route navigation. Valternative imports and manages the entire fleet, handling insurance, maintenance, servicing, and critically, unlimited battery swaps through weekly rental agreements reportedly around R4,000 or tiered lower depending on driver commitment levels. This removes the massive upfront capital barrier—over R200,000 for comparable EV purchases—that previously locked township-based drivers out of electric vehicle ownership entirely.

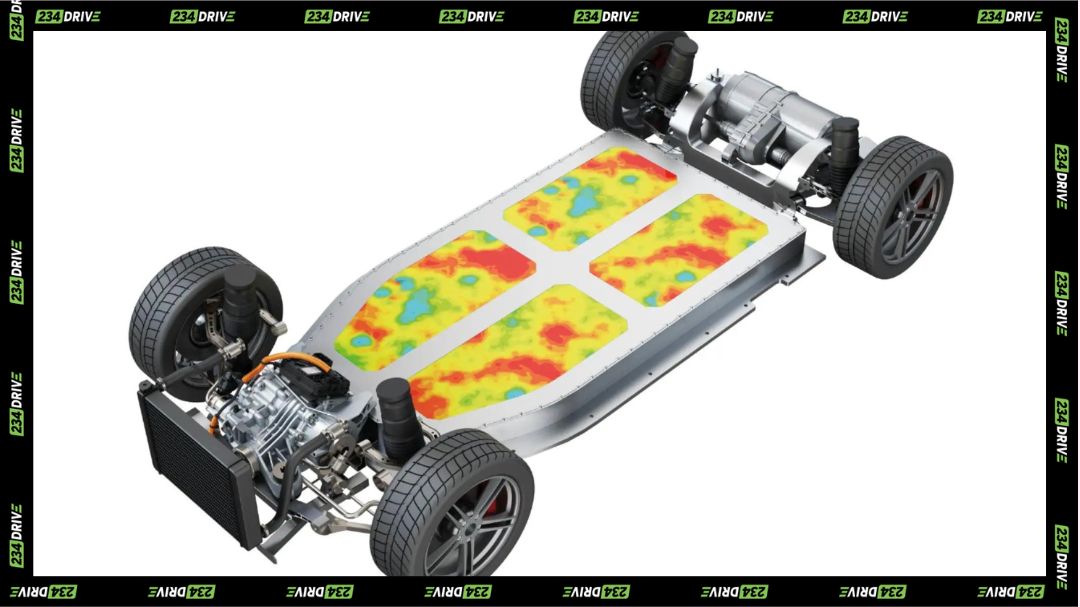

The battery-swap infrastructure represents the genuine innovation breakthrough here. Valternative Energy operates over 100 swap stations across South Africa, initially built for its electric motorbike fleet but now expanded to accommodate car batteries. Drivers experiencing low charge don’t hunt for scarce public charging points or wait 30-60 minutes plugged in—they simply pull into a Valternative hub, technicians extract the depleted battery pack, slot in a fully charged replacement, and drivers are back on the road in under 60 seconds. Each station incorporates solar panels or hybrid backup systems, ensuring operation continues during Eskom power outages that regularly paralyse South Africa’s national grid. This off-grid capability transforms electric vehicles from grid-dependent technology into energy-independent assets, a critical distinction in African markets where infrastructure reliability remains inconsistent.

For drivers, the economics prove transformative rather than merely competitive. Traditional petrol-powered Uber vehicles burn R200-R300 daily in fuel costs alone for typical ride-hailing mileage across Johannesburg’s sprawling metropolitan area. Eliminating fuel expenses entirely while bundling maintenance, insurance, and unlimited battery swaps into predictable weekly rental fees delivers immediate cashflow improvements. Early adopters report 15-25% higher net take-home income, driven both by eliminated fuel costs and increased productivity—the near-instant battery swaps enable 20-30% more trips per shift compared to petrol vehicles requiring refuelling stops. The rental model also eliminates debt financing stress, providing pathway-to-ownership options without crushing monthly loan repayments that drain earnings from independent contractors already operating on thin margins in South Africa’s competitive ride-hailing market.

Valternative Energy handles fleet supply, vehicle maintenance, battery infrastructure, and swap station operations while Uber provides the rider platform, driver network, and brand recognition that generates consistent trip demand. This division of labour mirrors successful infrastructure-as-a-service models emerging globally, where specialised energy companies handle the complex hardware and logistics while platform operators focus on marketplace dynamics. Valternative’s existing track record strengthens credibility—the company has already deployed over 1,000 electric motorbikes for Uber Moto service and created 760 jobs, targeting 3,000 positions by year-end 2026. The battery-swap stations serve both motorbike and car fleets simultaneously, creating operational efficiency and scale economics that standalone EV charging networks struggle to achieve in lower-density markets.

This launch signals Uber’s strategic recognition that traditional charging infrastructure won’t scale fast enough in emerging markets constrained by unreliable grids, limited capital for public charging buildout, and price-sensitive consumers. Battery swaps sidestep these obstacles entirely, decoupling EV adoption from public infrastructure development timelines that stretch across years or decades. The Johannesburg pilot positions Uber to replicate this model across other African cities—Cape Town, Durban, Nairobi, Lagos—where identical challenges around grid reliability, fuel costs, and infrastructure gaps constrain electric vehicle adoption. Success here unlocks continent-wide expansion using proven operational playbooks rather than experimental approaches, accelerating Uber’s stated goal of achieving 100% zero-emission rides globally by 2040 while simultaneously opening massive underserved markets to platform participation.

China’s electric vehicle ecosystem offers instructive comparison on execution velocity and scale. Chinese ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing operates hundreds of thousands of EVs supported by thousands of battery-swap stations built by companies like Nio and Aulton, with swap times consistently under five minutes and some next-generation stations achieving sub-three-minute exchanges. Nio alone surpassed 2,000 swap stations across China by mid-2024, completing over 40 million battery swaps since launch, with stations designed for 400+ swaps daily. The infrastructure density and standardisation enable seamless long-distance EV travel without range anxiety, proving battery swaps can scale to national transportation infrastructure when properly capitalised and coordinated. European and North American markets largely rejected battery swaps in favour of fast-charging networks, betting on improving charge speeds and expanded station coverage—a strategy that works where grid reliability remains high and capital availability supports dense charging infrastructure deployment.

Valternative’s South African deployment mirrors China’s approach more than Western charging-focused strategies, adapting battery-swap economics to African contexts where solar-backed off-grid resilience matters more than ultimate swap speed. The company moved from initial electric motorbike launches to four-wheel vehicle integration within roughly 18 months, demonstrating operational agility often missing from large-scale infrastructure projects. Achieving 70-vehicle deployment by late November 2025 with a clear scaling roadmap to 350 vehicles by late January 2026 shows disciplined execution—certifications cleared, supply chains established, driver training completed, and station network proven functional under real-world load-shedding conditions before announcing public launch.

Uber announced a separate global partnership with Chinese EV manufacturer BYD in 2024, aiming to introduce models like the Atto 3 crossover SUV across various markets including potential future South African expansion. However, the current Uber Go Electric launch exclusively uses Henrey Minicars, likely reflecting price positioning and operational fit rather than any technical limitation. BYD vehicles command higher price points and target different rider segments—business travellers, airport runs, premium urban mobility—while the Henrey Minicar focuses squarely on budget-conscious riders and maximum driver income efficiency. The dual-brand strategy suggests Uber will segment its South African electric fleet by service tier as the market matures, reserving BYD vehicles for Uber Comfort or Uber Premier categories while Henrey Minicars anchor the high-volume Uber Go segment.

The social impact dimension distinguishes this launch from typical mobility-as-a-service rollouts in developed markets. By eliminating upfront vehicle purchase requirements and providing predictable cost structures, Uber Go Electric opens ride-hailing income opportunities to township residents previously excluded by capital constraints. Traditional vehicle financing requires credit history, stable employment proof, and substantial down payments—barriers that systematically exclude informal economy workers and younger demographics across South African townships. The rental model with pathway-to-ownership options bypasses these gatekeepers entirely, democratising access to gig economy income streams that can provide R8,000-R15,000 monthly earnings for active drivers. Valternative’s job creation targets—3,000 positions by year-end 2026—encompass not just drivers but station technicians, maintenance crews, logistics coordinators, and administrative support roles, multiplying economic impact beyond individual driver earnings.

This marks the shift from electric vehicle hype to fleet-scale operations in African markets, proving that EVs can compete economically without subsidies when deployment models match local conditions. Should African governments treat battery-swap infrastructure like public utilities—providing land access, streamlined permitting, and grid connection priority—to accelerate zero-emission transport adoption, or will private operators like Valternative continue building independent networks that bypass unreliable public systems entirely?