Uganda’s Kiira Motors Corporation is currently midway through a statement-making 13,000 km electric bus expedition from Kampala to Cape Town, and the numbers tell a compelling story about African manufacturing capability. As of 28th November, 2025, the Kayoola E-Coach 13M has covered 2,370 kilometres—roughly 18% of the total route—reaching Mpika, Zambia, after successfully traversing Tanzania’s challenging 1,771 km leg. The journey isn’t just a publicity stunt; it’s a live stress test of battery performance across varied elevations, temperatures, and road conditions, whilst demonstrating that African-made electric vehicles can deliver reliable long-distance public transport without the fuel costs and emissions of diesel alternatives.

The expedition launched on 20th November, 2025, under the banner “From the Pearl to the Cape,” crossing six countries: Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, Botswana, Eswatini, and South Africa. The 30-day timeline is ambitious, requiring consistent charging infrastructure coordination and route planning across borders with varying electrical grid reliability. Yet the bus has maintained zero safety incidents whilst avoiding 1,109 kg of CO₂ emissions compared to equivalent diesel transport. The vehicle’s efficiency—0.85 kWh per kilometre—proves that electric buses can operate economically even on African roads, where potholes, dust, and inconsistent surfaces typically punish vehicle drivetrains. For rural communities watching this journey unfold, the implications are profound: locally built electric buses could slash fuel costs, reduce air pollution in congested cities, and create sustainable manufacturing jobs without perpetual dependence on imported vehicles.

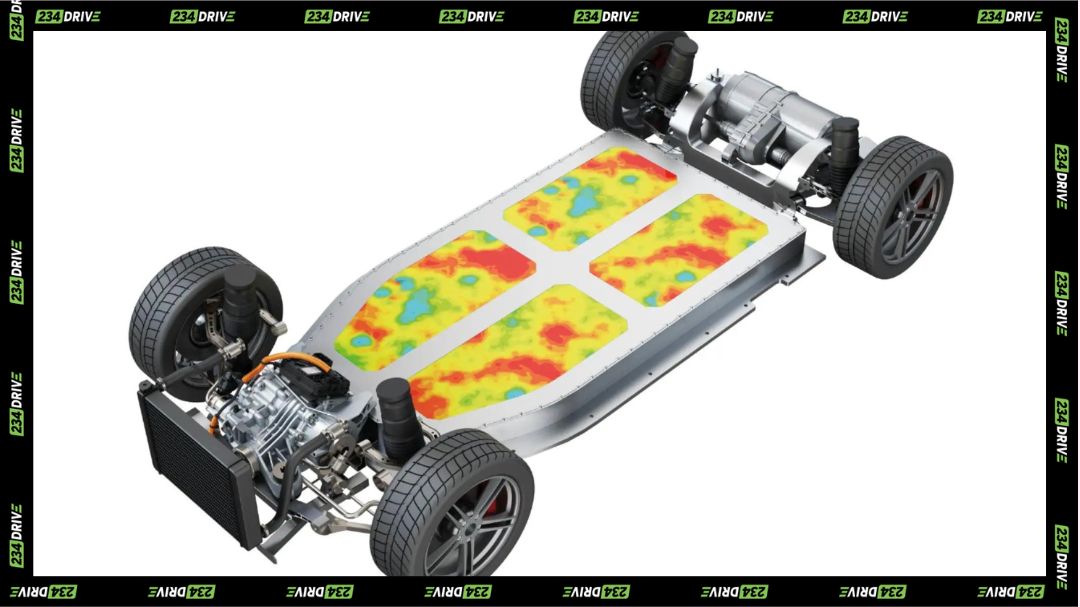

The Kayoola E-Coach 13M represents Uganda’s most advanced electric vehicle to date. Powered by a 400 kW electric motor delivering 5,000 Nm of torque, the bus draws from a 422 kWh lithium-ion battery pack that provides up to 500 km of range per charge. Top speed is capped at 100 km/h, prioritising efficiency over speed—a sensible choice for intercity routes where reliability matters more than acceleration. The premium interior configuration seats up to 64 passengers with Wi-Fi, USB charging ports, and LCD screens, positioning it competitively against imported Chinese and European coaches that dominate Africa’s bus market. This isn’t a stripped-down prototype—it’s a fully specced commercial vehicle designed to compete on comfort and features whilst delivering zero tailpipe emissions.

Kiira Motors’ strategy hinges on proving viability through real-world demonstration rather than lab testing. By traversing 13,000 km of actual African roads—not controlled test tracks—the company generates data on battery degradation, charging infrastructure gaps, and mechanical reliability that no white paper can replicate. The Tanzania leg alone covered 1,771 km from Mutukula to Tunduma, passing through Dodoma and navigating the country’s notorious road quality variations. That the bus maintains its 0.85 kWh/km efficiency across such diverse conditions validates Kiira’s engineering choices: robust suspension design, thermal management systems capable of handling equatorial heat, and battery chemistry optimised for deep discharge cycles rather than rapid acceleration.

The expedition’s commercial objective is to secure 1,000 bus orders from African governments and private transport operators. That target isn’t unrealistic. African cities are choking on diesel fumes, fuel price volatility destabilises transport budgets, and imported buses require expensive foreign-currency spare parts. A locally manufactured electric alternative addresses all three pain points simultaneously. MTN Uganda, the expedition’s primary sponsor, sees strategic value in associating its brand with homegrown innovation and sustainable infrastructure—recognition that African consumers increasingly favour products that demonstrate continental engineering capability. The journey’s live updates via Kiira Motors’ official channels have generated significant social media engagement, turning engineering validation into national pride.

What’s particularly notable is what the Kayoola isn’t: it’s not a solar-hybrid novelty or a short-range urban shuttle. Earlier Kiira prototypes featured solar panels, leading to confusion about the E-Coach 13M’s powertrain, but this expedition vehicle relies entirely on battery-electric propulsion with strategic charging stops. That design choice reflects market reality—African transport operators need range and payload capacity, not experimental technology that might strand passengers. The 422 kWh battery pack is substantial enough for genuine intercity service, and the 500 km range matches or exceeds diesel buses’ practical daily operation before refuelling. Charging infrastructure remains the bottleneck, but the expedition demonstrates that with planning and partnerships, cross-border electric bus service is viable today, not in some distant future.

Compare this to Europe’s electric bus rollout, where manufacturers like BYD, Solaris, and VDL moved from prototype to fleet deployment in under five years by focusing on urban routes with guaranteed charging infrastructure. London’s electric bus fleet reached 950 vehicles by 2024, but those buses operate on fixed routes with depot charging—far less challenging than a 13,000 km expedition across six countries. Kiira’s approach is riskier but strategically smarter for African markets: prove the technology works in worst-case scenarios, and urban deployment becomes trivial by comparison. If the Kayoola can handle Zambian rural roads and border crossing delays, city transport authorities have no technical excuse to avoid adoption.

The expedition’s progress through Zambia marks a critical phase. The country’s road network includes long stretches between population centres, testing the battery’s range claims under real load conditions. Mpika sits roughly halfway between Tanzania’s southern border and Zambia’s capital Lusaka, meaning the team has successfully navigated both Tanzania’s central corridor and Zambia’s less-developed northern routes. Each kilometre covered without mechanical failure or battery performance degradation strengthens Kiira’s commercial case. The 2,017 kWh consumed so far—meticulously tracked and publicly reported—provides transparency that builds trust with potential customers wary of inflated manufacturer claims.

The human-interest dimension resonates beyond statistics. Ugandan engineers, often overlooked in global automotive narratives, are demonstrating technical competence that rivals established manufacturers. The expedition crew includes drivers, technicians, and support staff whose expertise in managing electric drivetrains challenges stereotypes about African technical capacity. For young Africans considering engineering careers, this journey proves that cutting-edge work happens on the continent, not just in Detroit, Stuttgart, or Shenzhen. The Kayoola’s every successful charging stop and border crossing reinforces that African problems require African solutions—built by Africans who understand the terrain, climate, and economic constraints intimately.

The commercial implications extend beyond buses. If Kiira succeeds in securing significant orders, it validates localised electric vehicle manufacturing as economically viable, potentially attracting investment in battery production, electric motor assembly, and charging infrastructure development. Uganda’s automotive sector could become a regional hub, exporting vehicles to neighbouring countries whilst creating thousands of manufacturing jobs. The avoided CO₂ emissions—already exceeding 1,100 kg—represent a tiny fraction of potential continental impact if electric buses replace even 10% of Africa’s diesel fleet.

This marks the transition from electric vehicle theory to operational proof in Africa. The question isn’t whether electric buses can technically function on African roads—the Kayoola’s 2,370 km answer that emphatically. The question is whether African governments will prioritise procurement policies that favour regional manufacturers, offer financing mechanisms that overcome higher upfront costs, and invest in charging infrastructure that makes fleet-scale adoption practical. Kiira has delivered the technology. The next move belongs to transport ministries and city authorities: will they back African manufacturing with concrete orders, or continue importing diesel buses from Asia whilst environmental and economic costs compound?